Keegan, Ferguson, Cantona and a collapse: The inside story of the 1995/96 title race

Newcastle let a 12-point lead slip as Sir Alex Ferguson masterminded another title run. Miguel Delaney speaks to those involved in one of the most iconic battles in Premier League history

It is half-time at a pulsating St James’ Park, at the key juncture in the title race, and Alex Ferguson realises he needs to get back to basics and into the heads of his players. A callow Manchester United have been absolutely battered by Newcastle United, but it’s still 0-0, so the great Scot knows he must hammer one message home.

“Are you happy with those standards?” Ferguson asks his players. “Are they the standards of Manchester United? Can you really say, after that, you’ve shown you want this title as much as Newcastle?”

In the home dressing room, Kevin Keegan is relatively relaxed.

“That was fantastic,” the Newcastle manager says. “Let’s go and beat them… more of the same.”

That match on Monday 4 March 1996 had certainly been more of the same for the season up to that point. Newcastle were in irresistible attacking form and leading the way, setting a furious pace; Man United were not yet themselves, but were still there, still digging in.

That was the ominous reality for Newcastle despite their first half, and many of their players were already starting to doubt whether they could sustain the same level of performance without reward. Keegan would later admit “it was already in the back of my mind that it might not be our night”.

Peter Schmeichel, whose defiant performance was the only reason the score was still 0-0, caught the mood of the United players

“We knew in games like this there was a storm we needed to weather. If we could get past that point, we would start getting chances.”

They were waiting for the moment to pounce, to show what it really took.

Just as that first half summed up the title race to that point, the whole game would prove a microcosm of the entire season.

That 1995-96 campaign has become remembered for more football culture imprints than almost any other – Alan Hansen’s “kids”, Tony Yeboah’s volley, Eric Cantona’s return and redemption, 4-3, grey shirts, white suits, “I will love it” – but it is more than anything a precious illustration of how the game actually works, and how it is won.

It was not just a vintage Premier League season, but a vintage title run-in, and the ultimate story of a race that becomes a chase.

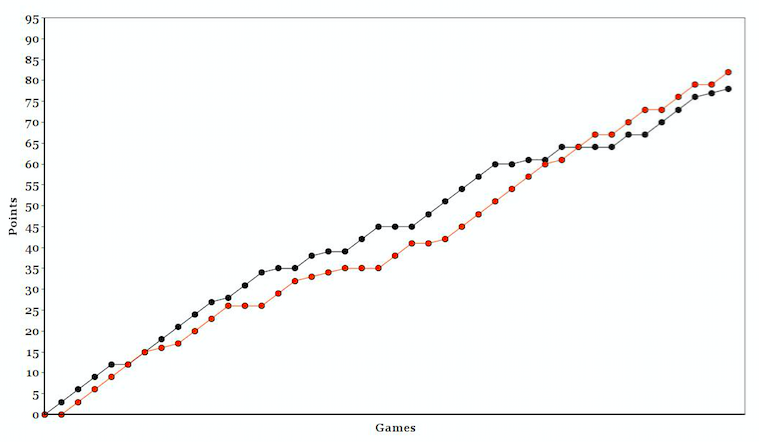

No team in English history has ever lost a lead as big as Newcastle United’s in that season.

No team in English history has ever reeled in a team to beat them in the manner Manchester United did that season.

Wrapped up in all of that are themes that go way beyond the question of how much was down to Newcastle “bottling it” and how much was United so predatorily stalking them. There was how you build teams, how you finish seasons, how you play and how morally pragmatic any prospective champions can be. Out of all that, there were also deeper issues of redemption and unfulfilled ambition, as well as the legacy of teams who don’t win anything.

For so much of the season, though, these complications seemed so far away for Newcastle. They were so easily freewheeling.

One of the most resonant themes of the 1995-96 season was the value of youth, and there was an irony to that, because among Newcastle’s defining traits was a certain innocence. That applied to how they played, and the fact it was a first title challenge since 1927.

It was also personified by the manager, who powered the club with a wide-eyed earnestness and enthusiasm that bordered on the evangelical.

Any cynicism at Keegan’s approach was seared by the speed of the club’s rise. Newcastle went from near the bottom of the second tier to the top of the Premier League in three years, making true believers out of almost everyone along the way – not least the players Keegan persuaded to sign for him, like Rob Lee.

“It was the right time for the club, the right manager and the right team,” Lee tells The Independent. “Just the energy around the whole area because of that team.

“What he was very, very good at was persuading people, especially to come play for him. That was the manager’s job, and what he was brilliant at. It’s unheard of now. Players would just be looking at the big six.

“When we got promoted, I remember him standing there saying ‘Alex Ferguson, we’re coming for your title.’ Everyone thought he was mad. That’s the way he was, fired by belief.”

Zeal, even, that translated into one of the most memorable starts to a season English football has seen.

Newcastle won nine of their first 10 games, and 20 of their first 26. There was a sweeping power to their football that took everyone along with it, seen in so many goals, and heard in the fervent St James’ Park stands.

“It was special,” Lee says. “I used to walk out with that team and think ‘we can beat anybody, genuinely anybody.’ I didn’t fear anyone. I didn’t fear Man United because I’d look around at the players we had, Les Ferdinand, Peter Beardsley, David Ginola, Keith Gillespie. They could win any game.”

Perhaps the signature game was the home win over Manchester City on 16 September, a 3-1 that could have been a 10-1. It had it all, from the flowing wing-play of Ginola and Gillespie that initiated wave after wave of attack, to the force and finesse of Ferdinand. There was even the usual concession of a goal for good measure, but Newcastle had already made the game secure through that signature move: one of the wingers – in this case Gillespie – crossing for Ferdinand to head in.

It’s hard to overstate now what an impression such images made. Newcastle were blowing everyone away, to go with all opposition.

Everyone wanted to watch them. Most people wanted them to win.

“I’d be coming back to London and, inevitably, someone would come up to you,” Ferdinand tells The Independent. “They’d say ‘I’m not a Newcastle supporter but whenever they’re on the box, I watch them, because I know there are going to be goals.’”

The ease with which Newcastle played at that point reflected the simplicity of the approach. This was a classic case of a team of very good players just being put in their best positions, and encouraged – nay, impassioned – to express themselves.

“That’s all we used to do,” Lee says. “Kevin had unique management skills. He wasn’t into the coaching they’d do now, or tactics. He was a superstar who’d played at a very high level, under great managers like Bill Shankly, and he wanted to play the game how he played.

“I asked him once what he did, and he said ‘Rob, I buy good players, and I let them play.’ We rarely changed formation, unless we had major injuries. I think we played three at the back maybe twice. We always played 4-4-2.”

From there, the only real instructions were to Ginola and Gillespie. Keegan would point to Ferdinand and tell them: “Supply him with crosses, because he’s the best header of the ball in the country.”

It led to the best of times for Ferdinand, who describes it as a “striker’s dream”. He hit 13 in the first 10 games. Keegan kept hitting the right notes.

Squad meetings were short, and training was uncomplicated, usually intensely competitive five-a-sides.

From those, assistant manager Terry McDermott would generally offer little bits of technical advice, whereas for Keegan it was almost entirely motivational. He would beckon players over, put two hands on their face, and basically grip with the same zeal.

“He tried to get into people’s minds,” Ferdinand says. “He’d make you feel invincible.”

From that, Keegan didn’t feel the need to say too much before matches. He’d often just making a show of picking up the opposition team sheet and declaring “I wouldn’t have any of them, we should be two up inside 10 minutes”.

Big into “positive thinking”, Keegan would look to paint pictures for his squad to motivate them, and at one point drew the analogy of a snowball.

“It keeps going down the hill and getting bigger and bigger.”

Left-back John Beresford, one of the livelier members of the squad, decided to chirp up. “But it could hit a wall and smash?”

Keegan looked at him for a second and, overlooking any humour, shot back with typical earnestness. “No, if you build it big enough it will go through it.”

This is what was happening with Newcastle. They had just kept on rolling and smashing through most obstacles, to eventually go 12 points clear in January, almost without pausing for thought. Belief was sufficient.

The problems began when they had to start thinking.

***

Manchester United, by contrast, had plenty to think about in that first half of the season. The entire year of 1995 had been one of the most tumultuous in the club’s modern history, kicked off – literally – by Eric Cantona’s notorious night at Selhurst Park. That controversy ensured he was still suspended for the start of the season, but wasn’t the only star missing. Ferguson had taken the stunning decision to sell Paul Ince, Mark Hughes and Andrei Kanchelskis that summer, in a move that brought huge debate about the manager’s own future. That debate only ratcheted up after the 3-1 defeat to Aston Villa in the opening game of the season, that brought Alan Hansen’s famous criticism – “you can’t win anything with kids” – on Match of the Day.

Old Trafford’s North Stand was being redeveloped at the time, and the barrenness of the terrace almost seemed to reflect the austerity of the team. If you wanted to get Arthurian about it, you could say it was the representation of a land without its king.

Cantona would return and score a penalty against Liverpool on 1 October, but it would take him a few months to get up to speed. In that time, United could rarely keep the same pace. There were flashes of the old electricity – like 4-1 wins against Chelsea and Southampton, as well as an early 2-1 victory over champions Blackburn Rovers – but they were still a team hanging in there rather than really pushing Newcastle.

It said much that United assertively beat the leaders 2-0 at Christmas to cut the gap from 10 points to seven, only to immediately squander that by losing 4-1 to Tottenham Hotspur and drawing 0-0 at home to Aston Villa.

A week later, Newcastle beat Coventry City 1-0 to go 12 points clear.

That is the figure from this title race that has gone down in history, but it actually only lasted two days. The complications of the fixture list meant Newcastle had a game in hand throughout much of this period, and United’s corresponding match that week was away to West Ham United.

Cantona scored the only goal of the game after nine minutes, firing the ball high into the net from a difficult angle. It was a symbolic victory given what had happened the previous season, and a sign of things to come.

You might even say it was the true start of United’s chase, in a reverse of how the same fixture had so dramatically ended their title challenge in 1994-95.

Cantona was picking up form and so, consequently, were the team.

United were still nine points behind having played a game more, however, a gap that was to remain in place for another month.

The key was that it would never again get bigger. This was where the run-in really began, where the hunt would start.

Gillespie wrote in his autobiography that United “lulled everyone into a false sense of security”. It was insight into Newcastle’s thinking, that Ferguson would typically start to play on.

He began to pointedly repeat the same message to his players. “Newcastle are the type of team that give you a chance.” He knew they were vulnerable, and would struggle under pressure.

On the other side, he was emboldening the mental fortitude of his own team.

“He always told us that were better in the new year,” Schmeichel says. “So we had this belief that we are on our best form in the run-in.

“We still believed we could win it, but we’d been there before, for four seasons in a row – good and bad. I think that really helped us and probably worked against Newcastle.”

This marked a major difference between the teams. For all the talk of “kids”, and Ferguson’s great gamble in bringing through the ‘Class of 92’ en masse, United had more proven champions. They had the hard-bitten experience of figures like Schmeichel, Cantona, Keane, Steve Bruce, Denis Irwin and Gary Pallister.

These weren’t kids, but men who had faced every aspect of a title challenge, from leading to chasing and winning to failing.

“Everyone knew what we had to do,” Schmeichel says. “We were there to compete for the title, that’s why we were at Man United.”

Newcastle had almost none of this, as Ferdinand argues.

“When you look back through our team, only Peter Beardsley and David Ginola had really won anything. That played a major part. When we’d lose a game when we were nine points clear, the attitude was ‘it doesn’t matter, we’re still clear, got a game in hand.’ There wasn’t that sense of urgency.

“If we had the experience of winning something, we might have gone ‘right, we’ve lost three points, that doesn’t happen again’. There would have been an inquest, but the attitude among us was quite flippant.”

Even as Newcastle were still winning in early 1996, though, there was an increasing realisation something had changed. That victory over Coventry had seen them become 1-5 favourites for the title, but it had also seen a more untidy display. That was most visible in the shakiness of goalkeeper Pavel Srnicek.

It was most sensed, however, up front. Newcastle had lost some of their fluency. The chemistry of their attack had actually changed, and that was even before the notorious signing of Faustino Asprilla.

The 2-0 loss at Old Trafford had seen Gillespie pick up a freak abdominal injury, that put him out for a few months and removed some of the balance. Keegan moved Beardsley out to the right wing, but also decided to act on a growing feeling.

The Newcastle manager had already told Ferdinand the team was becoming “too reliant” on him. The injury to Gillespie had similarly put more onus on Ginola, so Keegan felt they needed something different. Asprilla was sensationally signed from Parma in a club record £7.5m deal.

Again, Keegan’s “passion” proved persuasive in convincing the Colombian to join.

Asprilla was certainly different, as indicated by the reason he was unavailable for training on Thursdays. The forward had to report to the Colombian embassy because he was on probation for firing a gun during his new year celebrations.

That difference of course extended to his ingenious – almost elastic – talent on the pitch.

This is why, for all the debate about Asprilla costing Newcastle the title, his individualism was arguably necessary. He displayed this in his very first game, coming off the bench against Middlesbrough to set up a Steve Watson equaliser and trigger a 2-1 comeback.

But this was also the growing problem with the leaders. They were too reliant on individual spark. A collective cohesion had broken down. They’d stopped scoring as much.

“There was a change,” Ferdinand says. “We had previously been so footloose, and getting the rub of the green in almost every situation. When it turned on us, it was difficult to pull it back.”

This is how that experience of the pressure of a race was so important. In the first half of the season, Newcastle could just play, and it meant they won. Now, they had to play to win.

It was a significant mental shift. It was nowhere near as easy.

“Mistakes crept in, and we started to make things complicated,” Gillespie said in his book. “It was a slippery slope.”

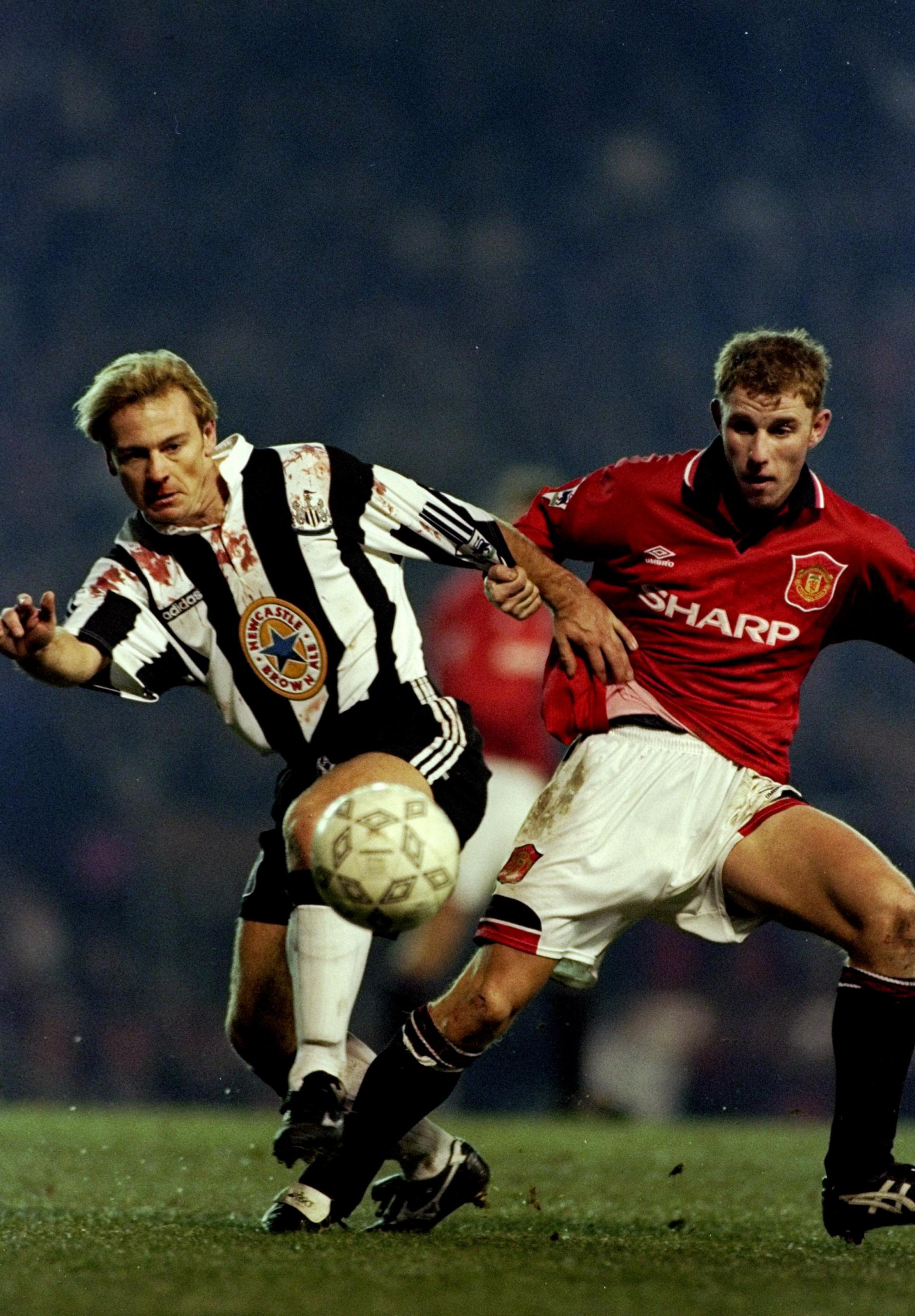

The first slip on that slope came on 21 February, as Newcastle lost 2-0 away to West Ham. They never stood up strong in the league again. That defeat was immediately followed by a 3-3 draw away to struggling Manchester City, where Asprilla got into trouble for losing his cool and elbowing Keith Curle.

It was another illustration of the pressure getting to them. At the same time, United were beginning to enjoy the chase, especially as they destroyed Bolton Wanderers 6-0 with what felt a watershed win.

The gap was now just four points, albeit with Newcastle having a game in hand.

The tightness of the situation only fired the next fixture: Newcastle United vs Manchester United at St James’ Park.

It was all building up to this. And might well come down to this.

***

It wasn’t just the circumstances that had built this game up. So had the entire city of Newcastle. It was all anyone had been talking about for weeks. The city felt alive with it. By kick-off, St James’ Park did too. Ferguson described it as “the lion’s den”. It was roaring.

There was no trepidation, only hope, if naturally tinged by a tightening but electrifying nervousness.

There was, to be fair, no trepidation among the Newcastle players. They rose to the atmosphere, and the occasion, with what was initially one of their best displays of the season.

They laid siege, and this time sensed a fragility in the visitors. The problems had actually started for United before the game, when Pallister suffered a back problem getting off the bus. Gary Neville had to come in at centre-half, and has since admitted the situation got to him, describing it as “a personal nightmare”.

“We got battered,” he said in his autobiography. “I kicked fresh air one time in the first half as Asprilla tormented me.”

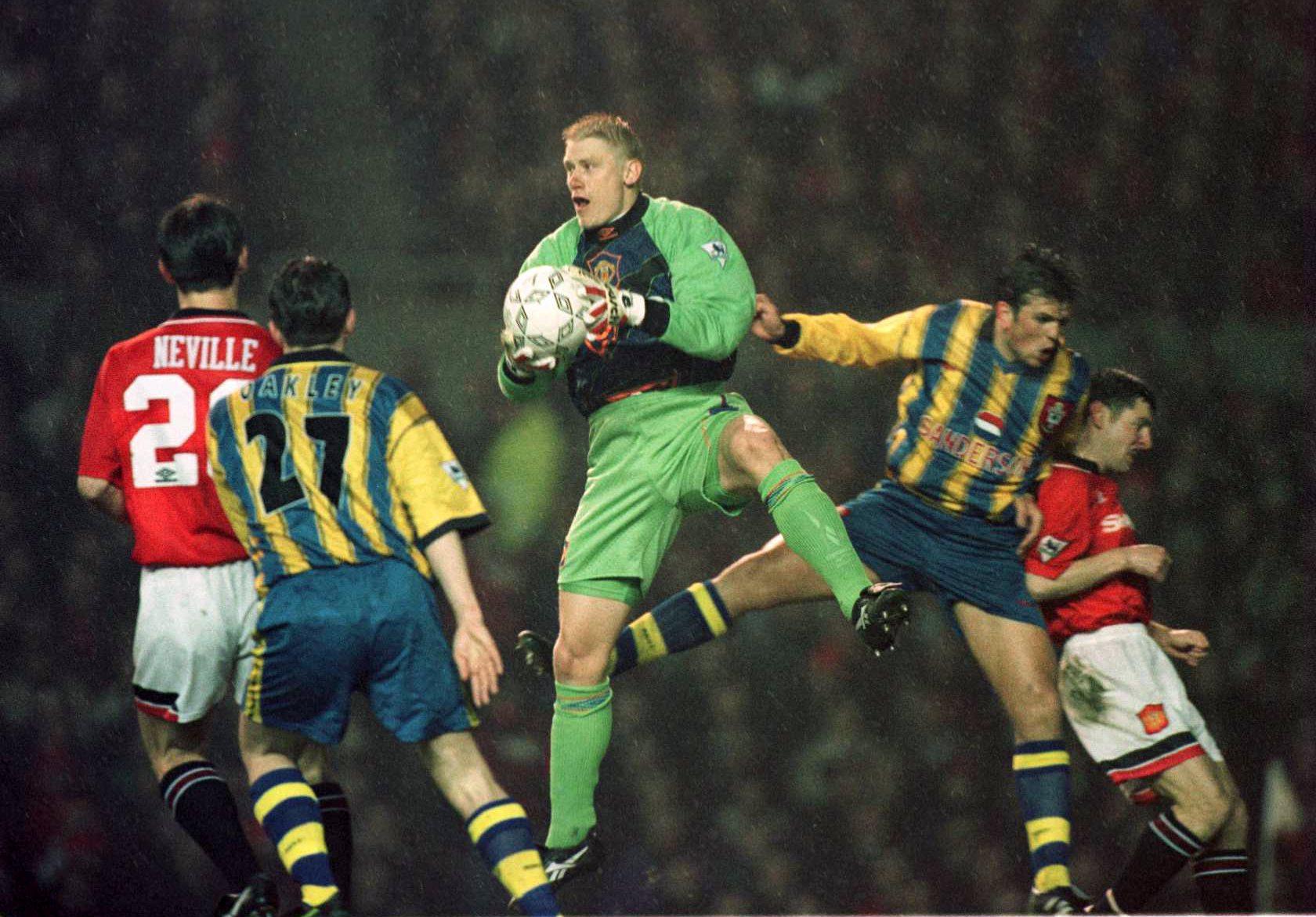

These were the problems Newcastle’s sheer relentlessness were causing. They had four chances in the first half alone that should have put them out of sight. There was one reason United were still in the game.

“The only difference was Peter Schmeichel,” Lee says. “I’ve never seen goalkeeping like that, really. He was probably the best goalkeeper in the world at the time, and in that game he was outstanding. He single-handedly kept us out.”

Well, not quite single-handedly. It was often both hands, a foot, or his entire body.

The first big chance came almost immediately, as Asprilla flicked on to put Ferdinand through. The striker beat a hesitant Bruce to the ball but in doing so took it a little bit too wide, allowing Schmeichel to totally smother the attack.

This was what so elevated the performance. It wasn’t just perfect goalkeeping. It was distinctive goalkeeping, featuring all of the signature saves that made Schmeichel the best in the world. Their very familiarity, and the force behind them, offered reassurance to a reeling United.

It was badly needed. Just moments later, Newcastle had their best chance of the match, as Asprilla played in Ferdinand with the most intricate of passes. The number-nine used his power to get past Bruce, before leathering a shot at goal.

“I hit it straight away… and he just comes out and spreads himself,” Ferdinand says. “That starfish, and a hand saves it out of nowhere.

“It was about pitting your wits against him.”

This was the extra challenge of facing Schmeichel. If saves like that are necessary instinct, they come from the most intelligent training. A forward like Ferdinand bearing down on goal might have been one of the most terrifying sights in the Premier League, but Schmeichel worked to ensure the sight of him coming out at you was just as intimidating.

It is why, when you ask the Dane about what was going through his head at those moments, he merely points to what went before.

“Everything is instinct, but it’s instinct built on training and training and training, so you don’t have to think,” Schmeichel explains. “It’s not like one of the strikers are one on one and you think ‘oh no, he’s going to score’. You don’t. You focus on what’s going to happen.

“One of the things I did over and over again when I was younger was that my coach would dribble the ball around the penalty box and then stop me – ‘stop! Where are your two posts?’ – and just by looking at where the lines are in relation to me I would have to tell him where. I learned to cover my angles really well. So when you’re faced with situations in the game when someone is one on one with you from an angle, I don’t think about where my posts are. I know I have them covered. That’s my instinct, but before that there’s a lot of hard work.

“I worked out a system where I would be intimidating for the striker. It’s nothing that I’m conscious about in the moment, but comes through hard training. I worked out how, if I could have my defenders pushing strikers down, I could come out and close strikers down. That was my job… you always try to achieve unbeatable.”

He achieved it that night. Even with powerful long shots from Asprilla and Beardsley, there were no scrambled parries. Schmeichel held them, and held them firmly. It had the double effect of fortifying United, and creating increasing doubt in Newcastle.

An obvious question is how a goalkeeper, given the reactive nature of the position, can mentally prime himself for a performance like that. Schmeichel actually insists he didn’t, but instead offers an insight into the kind of mindset in that team.

“This might sound boring, but part of the talent to play for Manchester United is that you can go into any venue and be the same. You have the same preparation, you have the same outlook on the pitch. You don’t look at the stands. All that is part of what happens. There’s nothing from the outside that has any influence on how you play. Nothing can make you nervous and really nothing can make you better. You just have the greater objective in your system. I can’t remember how many points we would have fallen behind if we’d lost, but you don’t think like that. You kind of stay neutral in your preparation so there’s no difference between playing Newcastle, who you’re chasing, or Bolton or QPR. I think this is part of why I ended up at Man United, and why all the guys I played with ended up there.

“Another thing about that period is that we had so many injuries. We were mentally prepared to just defend more than we normally would do.”

Ferguson, however, might have quibbled with that at half-time. While he effusively praised Schmeichel – “he defied them, and just kept defying them” – the manager vigorously questioned the backline, and especially Neville.

“Asprilla is beating you on the ground, he’s beating you in the air. What’s going on? Play like that second half and you’ve cost us the title.”

It was harsh, but Ferguson felt it necessary. He admitted in his autobiography this was one of the more meaningful team talks of his career, and a rare one where he went so basic.

It was clearly effective. There was already a distinctive shift in the psychology of the game, that had been signalled by a Ryan Giggs shot deflected wide just before the break.

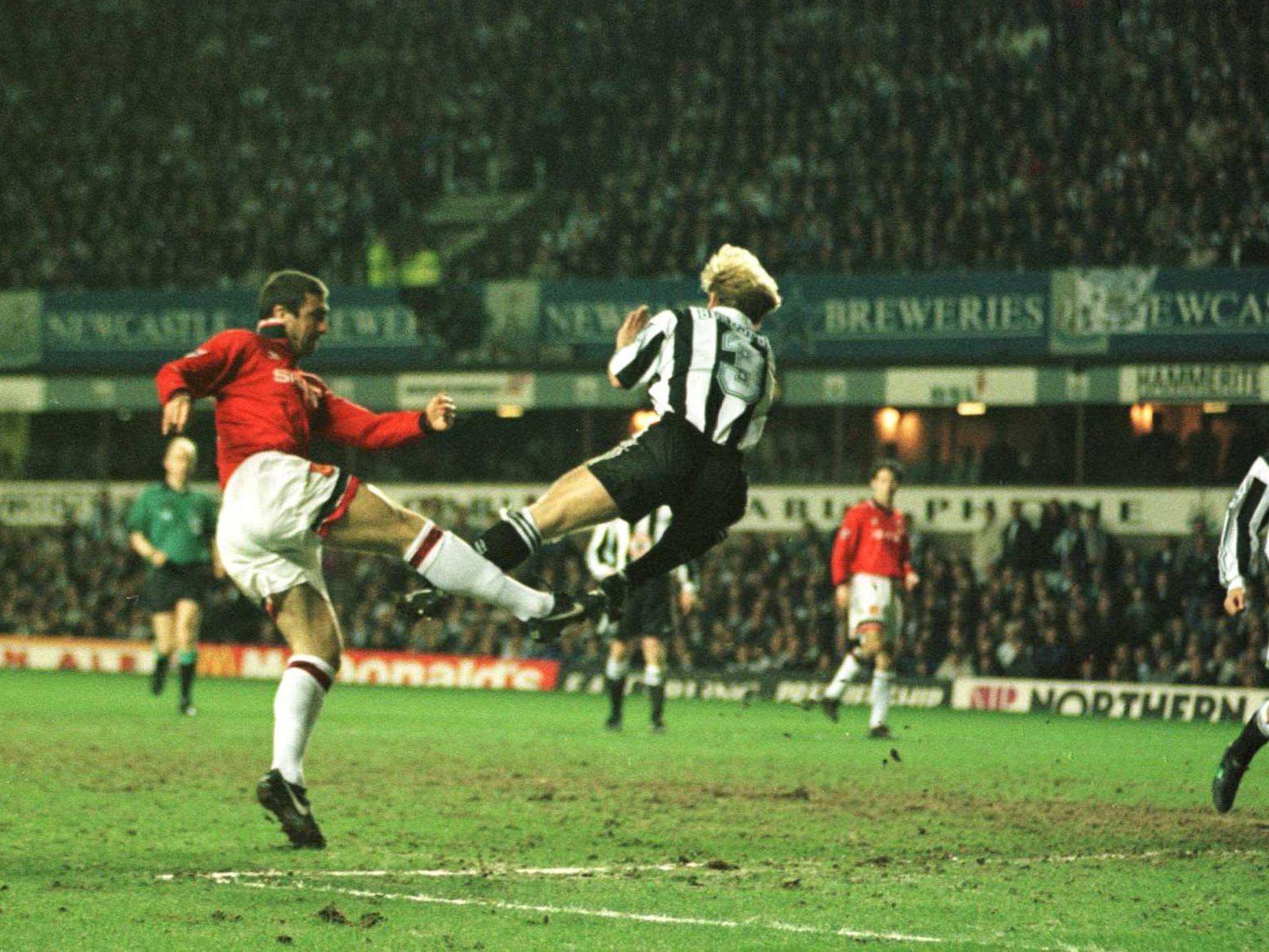

After it, United came out more assured. They were beginning to take command. Keane was starting to win everything in midfield, driving the play with his force rather than just looking to defy. It was one such tackle in the 51st minute that saw the Irishman beat David Batty to the ball, before playing the ball out to Phil Neville with a volleyed pass. Newcastle were suddenly in retreat, and panicking. The ball was played into Andy Cole, who brilliantly rode two challenges before slipping the ball back out to Neville. He clipped the ball to the back post and there, clinically, was Cantona.

It wasn’t his most exquisite finish, as the ball bobbled off the turf. It was one of his most important, as it bounced past Srnicek and in.

The intense concentration of the game had given way to a moment of real consequence. United, after all that, were in the lead.

There were still 38 minutes to play, but Newcastle were beaten. They never looked the same.

Again, the game was the season in microcosm. Now the momentum had shifted it wasn’t shifting back

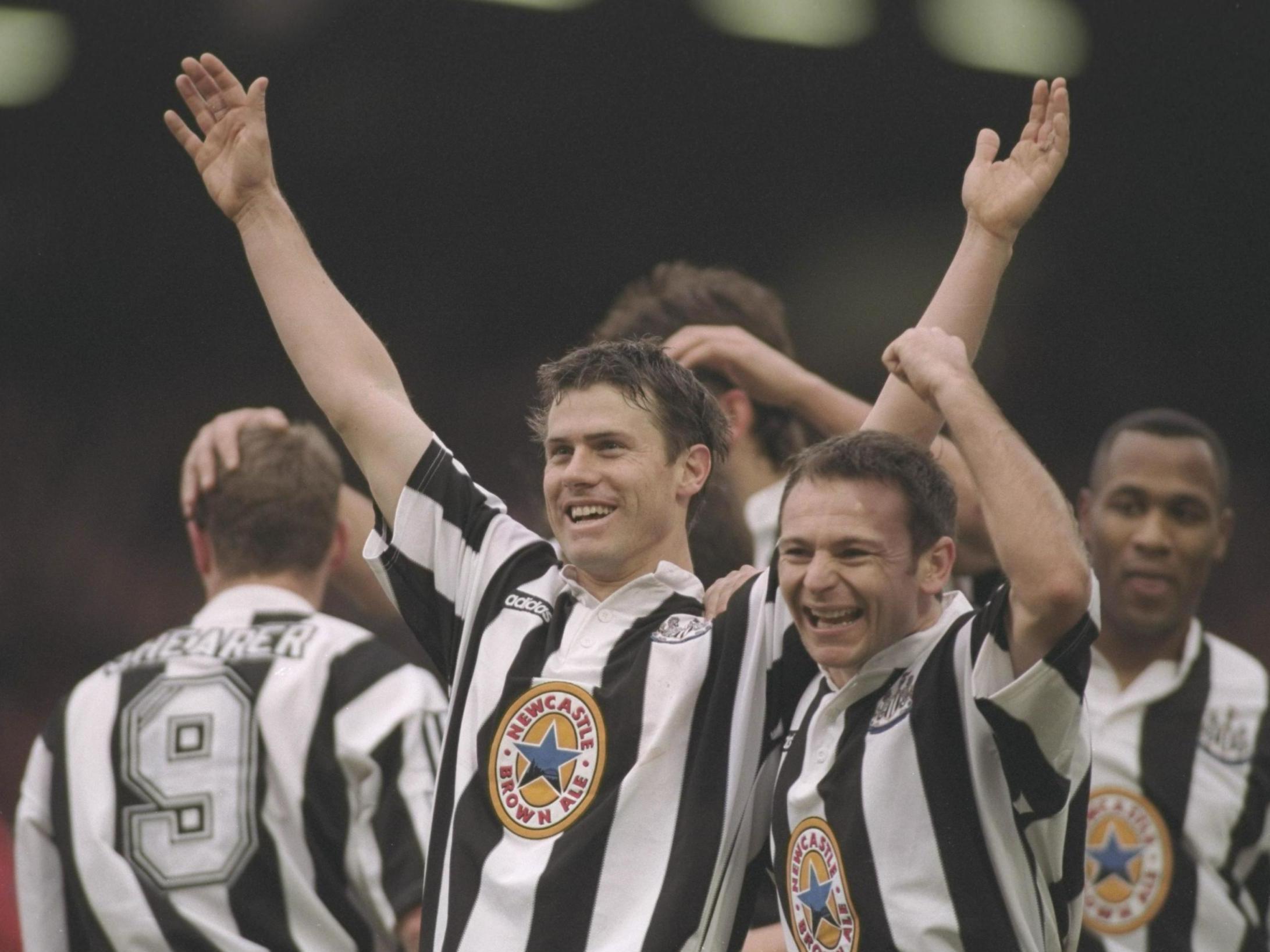

The Newcastle dressing room was described as “unsettlingly quiet” afterwards. Keegan broke the silence, attempting to reassure the players by pointing to how well they’d played. “Don’t get down about it,” he said. “Let’s go again.”

Years later, in his autobiography, he would describe Cantona’s goal as “the moment everything started to unravel for Newcastle”.

Everything was starting to come together for United.

***

It said much about the way things were going that United actually slipped up in the very next game, but even that worked in their favour. That was because they were 1-0 down away to QPR in the 97th minute, only for Cantona – of course – to head in an equaliser.

This was another difference. It’s impossible to overstate just how much impact Cantona had on that run-in. It is actually one aspect of his career that is arguably under-appreciated, amid all the plaudits for being one of the Premier League’s most transformative players. He that season the most decisive, probably to a level beyond anyone else in the competition’s history. It really can be counted.

In that run-in alone, there were six games where Cantona scored United’s only goal of the game. One was that equaliser against QPR, the other five were all match-winners in 1-0 wins. The goal against Newcastle kicked off a four-game spell when United scored only four goals, but all were scored by Cantona, and they together delivered a total of 10 points from 12. After that draw against QPR, there were second-half winners against Tottenham Hotspur and Arsenal. The goal against Spurs was a precise finish into the corner, the strike against Arsenal a bombastic volley. Another single-goal match-winner came against Coventry City a few weeks later, and that amid the trauma of Dave Busst’s leg break.

If that tragedy put the run-in into perspective, Cantona still displayed a vision beyond anyone else.

“It was demoralising,” Lee says. “We’d come in every week, and hear they’d won: 1-0, Cantona. Hadn’t played that well, 1-0, Cantona. For me, Schmeichel and Cantona won the title really. It was relentless.”

It was again that escalating effect, another element that fortified United’s belief and sapped Newcastle’s.

It was as if they were meeting every Cantona blow with a low. The contrast was striking.

While United were putting together a run that would see them win 13 of the last 15 games, Newcastle had one eight-game spell between 21 February and 8 April where they picked up a mere seven points from 24.

This was how their nine-point lead was actually obliterated in the space of just five weeks.

Keegan described it as “a collapse”.

“At the business end of the season, no team with title aspirations can hit that kind of form and expect to get away with it.”

In another contrast with United, it summed up the way things were going that even a rare plus ended up being a massive negative.

Newcastle more than played their part in one of the greatest ever Premier League games at Liverpool, only to still lose 4-3 to Stan Collymore’s goal in the very last minute. Keegan would attempt to talk up the positives of being involved in such a historic match, but his true feelings were illustrated straight away as he and McDermott slumped over the advertising hoardings.

Ferdinand and Ginola were two of the players instantly knew that defeat was pivotal, and that was maybe that for the title. In an interview with Martin Hardy for the book ‘Touching Distance’, McDermott came out with the following.

“Horrible, horrible. You can’t believe it, fucking sickening. In all my time in football, that’s the worst I’ve felt, ever… it’s sickening… sick, absolutely sick.”

Keegan would later describe it as “gut-wrenching” and “shattering”.

It felt like the tragedy of his whole managerial career, as if that endearing innocence was always destined to just end up causing the most intense pain.

Even before that match, he had spoken prophetically on Sky Sports about how “the danger is you can play really well and get beat here”.

There were just too many dramatic twists like this. Five days later, Newcastle were 1-0 up away to Blackburn in the 86th minute, only for local-boy Graham Fenton to score twice. In literally any other setting, the young striker would have been cheering his boyhood club on.

It was all becoming too much, but the reality was it had been getting to Keegan and his team long before.

Ian Wright remembers beating Newcastle 2-0 with Arsenal in that run-in, and just seeing a “fragile” and “anxious” team. Their own players could now feel the “nerves” in St James’ Park.

The fun had gone. Team talks were longer, and more rambling. Training was becoming tense. In the days after the Blackburn defeat, the players were running through the woods, when Keegan suddenly announced: “Anyone who goes out tonight won’t play for this club again.”

It was the first time he’d cancelled a team night out, evenings that had previously been seen as key to the squad spirit, where attendance was compulsory. Beresford was meanwhile dropped for the rest of the season for swearing at Keegan during the win over Villa, breaking one of the manager’s cardinal rules.

When Sir John Hall and the directors said they’d be willing to bring in another centre-back to stop leaking goals, Keegan resisted. “I’ll do it my way,” he said. This was now becoming the problem.

All of this of course came to a head with Keegan losing his head in one of the most famous moments in Premier League history: “I will love if we beat them… love it.”

The words, and images, are by now well known.

So is the source of it. Ferguson had questioned the motivation of the Leeds United team his side had so narrowly beaten 1-0 through a Keane goal in mid-April, basically challenging them to put in a similar performance in their fixture against Newcastle two weeks later. He had similarly wondered aloud about Keegan agreeing to play in Stuart Pearce’s testimonial just eight days after they were due to meet Nottingham Forest in the penultimate game of the season.

To almost everyone, and particularly the United players, these were obvious psychological ploys.

To Keegan, however, these were betrayals of the moral standards of the game.

He had actually gone in to that famous interview with Richard Keys and Andy Gray “right as rain… in good fettle”, according to McDermott, after winning a “scrap” of a game against Leeds 1-0. It was only as the interview went on, and the cans on his ears obscured how loud he was getting, that Keegan began to lose it.

It is that crescendo of a “love it” line that has naturally lived longest in the memory, and remains such a gloriously impotent show of emotion, but just as telling are some of the earlier comments. The creaks could be heard in the reference to the Pearce testimonial.

“We’re playing Notts Forest on Thursday, and he objected to that!”

It was as if he just couldn’t believe that Ferguson – Machiavelli in a manager’s overcoat, and a fanatic – would not play fair.

“Alex always seemed to take the view that everyone was out to get Manchester United,” Keegan would say in his autobiography. There was that naivety. This was to totally miss the point. It wasn’t that Ferguson believed everyone was out to get United. It was that he was trying to get any advantage possible, trying to nuance every single situation in his club’s favour.

Keegan did not like Ferguson at the time, and when McDermott immediately phoned his boss to ask him “what the fuck was that?”, the Newcastle manager merely responded “ah, sod him”.

Although they patched up their differences as ITV pundits for Euro 96, Keegan has remained unrepentant about that outburst.

“It was pathetic,” he wrote in his autobiography. “It was a cheap trick. Alex will no doubt be congratulated for striking some kind of psychological blow but, if that was the intention, I am happy to state I would never stoop to the same level.”

It’s also why he never rose to the same level.

For his part, Keegan did recognise this.

“What it proved to me was that Alex would do anything to win, whereas the same could not be said of me… it was maybe why he won so much as a manager, including 13 Premier League titles, and I didn’t.”

This is also the deeper point about that moment. It wasn’t that Ferguson had finally got to Keegan, for the decisive blow that would win the race. It was that Keegan had already lost the race. The day before that rant, United had beaten Nottingham Forest 5-0, in a performance that felt like the perfect release of their burgeoning talent. They now only had to go to Middlesbrough and get a win to be champions – and that was before Ian Woan’s thunderbolt ensured Newcastle slipped up 1-1 at Forest themselves.

Ferguson wrote that he felt that 5-0 “pushed Kevin to the limit”.

“It was an exercise in devastation at a crucial stage of the season and perhaps it made him realise that the championship was within our grasp".

By Sunday, after 3-0 win over Middlesbrough that felt like another glorious release, they were lifting the trophy.

United had the finest redemption, all of the doubts and debates about a young team banished by one of the most brilliant surges any league had ever seen. “It was just one of the best feelings,” Schmeichel says.

Newcastle had the ultimate collapse, all of the hope built up for months so quickly evaporating. It was the harshest of lessons.

***

In the immediate aftermath of Newcastle’s final game – another slip, albeit this time an inconsequential one as they drew 1-1 at home to Tottenham – Keegan of course attempted to put on a brave face. He was the first into the dressing room, telling the players they’d “been incredible” and how proud he was of them. A truer insight into his feelings was revealed when he was asked to bring the players out for a lap of honour. Keegan hesitated, and had to be coerced into it.

That was entirely natural, especially given the emotion in the stands. St James’ Park was still packed, and the stadium was showing its gushing appreciation. Many, however, were crying.

An innocence had been lost. Some around Newcastle still believed, even on that last day, they could win their first title since 1927.

They were instead subjected to the brutal reality of United’s relentlessness.

It is the great irony of that season, and winning in general. McDermott would later speak about how United wouldn’t really have missed that one trophy in that spectacular spell of success, whereas it would have meant everything to Newcastle. It was precisely because of that, though, only one side had the mentality to win it.

Keegan would admit Newcastle were “naive in many ways”.

For all the focus on United’s kids, they were the much more battle-hardened side. And that didn’t just apply to the experienced professionals, as Schmeichel argues.

“The kids – I say the kids – were brought into that squad having come all the way through the academy system, and all the learning in a high-performance environment. They were never fazed by anything really. There was always this belief.

“That’s how we ended up on top that season. We knew this was us, and all the experience we had, from four years of winning and challenging. Now, for Newcastle, it was a fantastic team, but they didn’t have that last bit. They didn’t have the experience.”

Schmeichel maintains it was the main difference between the teams.

Lee maintains it might have been different for Newcastle if Keegan had have stayed on. A further irony is that he had agreed a 10-year contract that summer – but not signed it. He instead resigned in January of the next season, with many believing he was “scarred” by what happened in 1995-96.

“Well, it must have done,” Lee says. “Kevin was a unique personality. And it’s a shame, because when you’re playing, you always think you’re going to get another season, that you’ll win next season.

"Well the next season we bought Alan Shearer, and I truly believe if Keegan had been there as long as Sir Alex that Newcastle would be there still. We had such a good team, it was inevitable we were going to win something eventually. Kevin leaving was a major blow. He was just right for the club. He gave them a team they could be proud of, and enjoy watching.

“Even now, people come up to me, not even Newcastle fans, ‘I remember that team’. No one remembers who finishes second, but they do our team.”

It is a statement that puts a spin on the idea of legacy, especially given debates about teams like Mauricio Pochettino’s Spurs.

For Ferdinand, however, it is still double-edged.

“I’m proud to have been part of a side that played a brand of football that everyone enjoyed watching. The unfortunate thing is you need something at the end. There’s not one of us now you speak to who will be satisfied with his time at Newcastle, because we should have won the league.

“There’s some satisfaction, but at the end of the day, it’s the one thing that haunts me that we didn’t win it.”

Lee believes it would have “changed football”. It instead changed Manchester United. Ferguson’s finest generation of talent had been given the ultimate finishing school, as well as the platform to finally win the Champions League.

They’d shown the standard required, in so many ways.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks