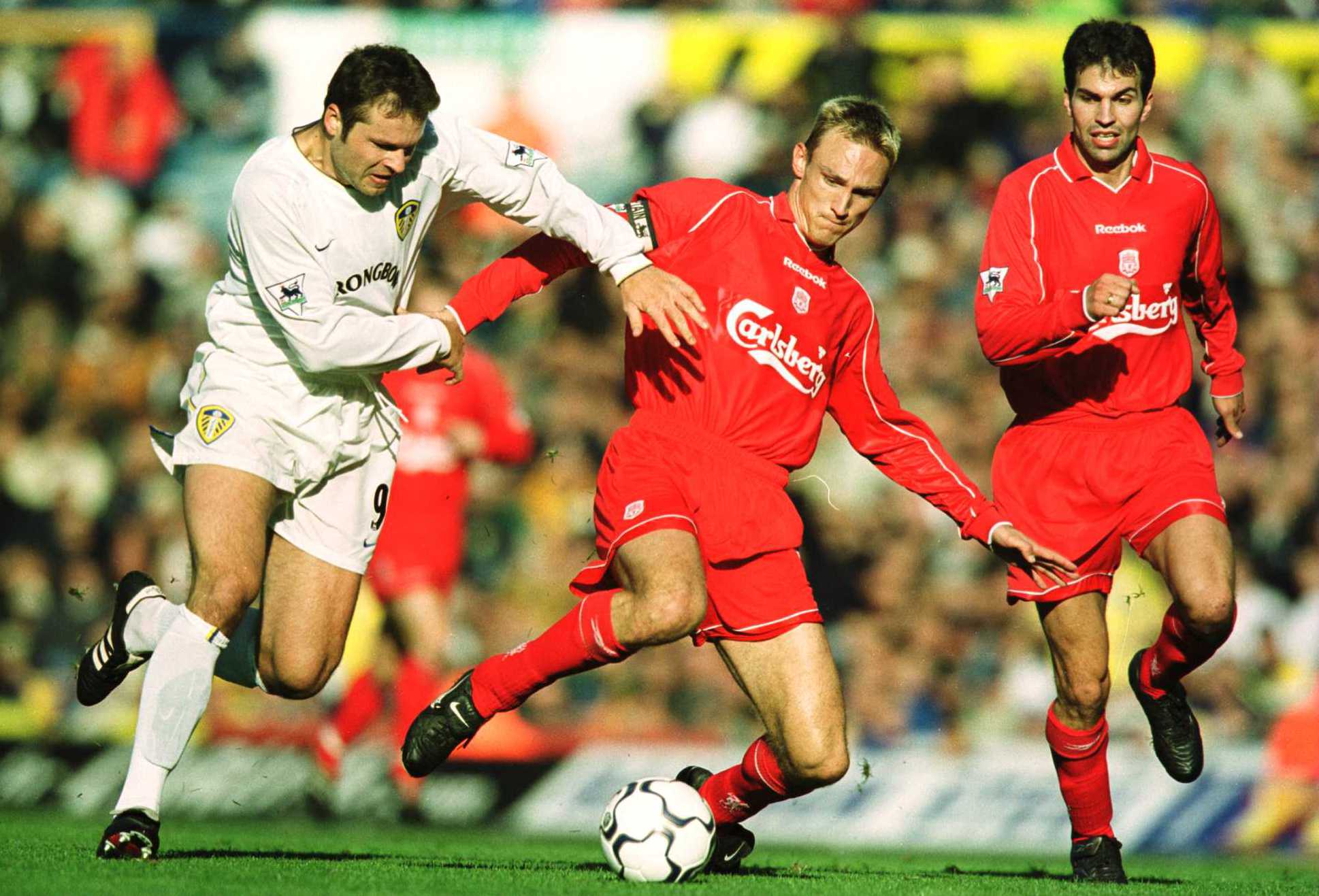

Leeds 4-3 Liverpool: Remembering a Mark Viduka masterclass in one of the Premier League’s greatest games

Leeds and Liverpool meet again this weekend 20 years after the Australian striker’s magical day at Elland Road

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was an archetype of its kind, a transparent example of a ‘moment that preceded unfortunate events.’

When Leeds United welcomed Liverpool to Elland Road for a Saturday lunchtime kick-off in the Premier League in November 2000, the wind was behind them.

The team managed by David O’Leary had finished third the previous season, and reached the Uefa Cup semi-final. His young squad oozed confidence, a kind of surly sureness about the world that comes of having not yet experienced the depths of its disappointments.

What had come before, for most of them, had been a quick-fire rise through the ranks of academy and youth football to become England’s third power. What came after, as has been extensively, painfully documented, was uniquely tragicomic, the sudden and yet predictable death that occurred when the club’s ambition finally caught up with it.

But for a moment in time, Leeds seemed untouchable, never more so than during a cold, bright autumn lunchtime when Liverpool were downed by a masterclass from Australian striker Mark Viduka.

“We felt invincible as a club at that time,” says former midfielder Eirik Bakke, then only 21, who started in midfield that day. “We attacked every game, we were impossible to play against. We were aggressive, entertaining. We believed we could beat anyone.

“What happened next was awful. We missed out [on the Champions League] by one point, and from there the finances became a mess.”

Leeds began the afternoon in 10th, and in the grip of an injury crisis. O’Leary had named only four substitutes, a kind of distress-signal flare telling the fans not to expect too much against Gerrard Houlier’s Reds.

Things started badly, and got worse. Sami Hyypia headed Liverpool in front after two minutes. Christian Ziege doubled the lead after 18. Both goals came from non-existent marking from free-kicks taken by former Elland Road favourite Gary McAllister, salt in the wound for the home crowd. The visitors looked ready to wipe the floor with poor, depleted Leeds.

“For me as a young player looking around the dressing room, we’ve only managed to name four subs, half the team is missing,” says ex-Leeds and England goalkeeper Paul Robinson. “We’re threadbare – it could be a really busy, horrible afternoon. We went a couple of goals down, but it’s in adversity that you find your best results.”

Leeds had already struggled that season in coming up against huge challenges with a weakened team. The previous month, their Champions League debut night had been ruined when an injury-ravaged side were tormented by Barcelona’s Rivaldo in the Nou Camp. Two weeks later, Manchester United crushed them 3-0 at Old Trafford, as Leeds laboured in the absence of Harry Kewell, Lucas Radebe, Danny Mills and Nigel Martyn. In the sunshine in west Yorkshire, the script was written for another pasting.

“A lot of players that day had hardly played for us before,” says Bakke. “Jacob Burns played, Jonathan Woodgate went off injured early and Danny Hay came on, and he’d never played. We had so many injuries. That’s what the game would have been remembered for if we’d lost heavily. Instead it’s remembered for Mark Viduka.”

The comeback began almost instantly. Ziege, distracted perhaps from having just scored his first Liverpool goal, was dispossessed by Alan Smith. The ball broke to Viduka, who lifted it impudently over Sander Westerveld in the Reds goal.

The equalizer shortly after half-time was all of Leeds’ own making, Gary Kelly crossed for Viduka to nod his second inside the near post. The game swung again when Vladimir Smicer slipped a cool shot past Robinson for 3-2, but it was to be little more than a set-up for the Australian to bring the house down.

“I can’t even recall another player scoring a hat-trick against me,” says ex-Liverpool goalkeeper Westerveld. “There were four in the Uefa Cup final [against Alaves in 2001], but I don’t remember at Liverpool or in Spain letting in four. Even against Real or Barcelona.

“It wasn’t that Viduka got four, it was the way he did it. The first one, he chipped me from a one-on-one. I made myself big and he clipped it over me. So I thought next time, stand up to him. Then in the second half, I stood up and made myself big, and he chipped me again in a different way.”

The Australian’s third and fourth – scored barley two minutes apart and which each took the roof off Elland Road – were a showcase of his unique talent.

The first was a work of endeavour; he collected the ball to feet with feather-light finesse and, in one motion, turned Markus Babbel and Patrick Berger and fizzed the ball in off Westerveld’s far post. The winner, a scarcely credible fourth, was opportunism mixed with devilish aplomb, scooping a finish over the goalkeeper after pouncing on a loose ball.

“Sometimes you walk off as a goalkeeper, you won 2-0 but you think you played shit,” says Westerveld. “That game at Leeds, I came off thinking ‘what happened?’ I had a good game but we lost 4-3. And I always used to blame myself. What can you do?

“The goals weren’t mistakes by us. His first goal, he was all by himself. We did everything right. We had the best back four in the league that year.”

“It was an incredible one-man performance,” adds Robinson. “The way Viduka dragged everybody up by the bootlaces.

“Liverpool were title challengers then, and we were just the new kids on the block. There was always a Leeds-Liverpool rivalry, but that was becoming more significant because we were a young, emerging team. People were taking notice of us.

“Viduka was one of the most laidback men, but with an edge. You had to be a good man-manager to get the best out of him, else you’d lose him. He’d be late for his own funeral. There was no point in fining him for turning up late. So you make a joke and accept that’s how he is. Then he pops up and scores four on the Saturday. That was the reward you got for managing him properly.”

The Australian lives a different pace of life these days. He called time on his playing career after leaving Newcastle in 2009, and these days runs a café overlooking the Croatian capital Zagreb, from where his father hails.

“He splits his time between Zagreb and Dubrovnik,” says his former Australia international teammate Burns, who played in Leeds’ midfield during the win against Liverpool. “I holidayed with Mark in Europe this summer and those games are what you reminisce on. We’re still talking about it 20 years later.

“He’s still as laidback as ever, same swagger as he had as a player. He took it all in his stride. It didn’t surprise anyone that he could turn up and do what he did to a massive club like Liverpool. When he got into his groove, he was unplayable.”

The season is best remembered for Leeds’ sensational run to the Champions League semi-final, but it’s the chronic overspend sanctioned by chairman Peter Ridsdale that left the biggest legacy. It’s one that Marcelo Bielsa’s class of 2020 are still recovering from.

O’Leary’s team had qualified for the Champions League by a single point in May 2000. Twelve months later, the roles were reversed, and despite Viduka’s heroics at Elland Road in the autumn Leeds failed to yield a return on the millions Ridsdale had splurged in the hope of creating a European dynasty.

“No one could have imagined what was going to happen 18 months, two years later,” says Robinson of the club’s relegation in 2004. “From those highs to where we ended up, it was awful.”

Bakke, now managing Sogndal in his native Norway, concurs. “We had been so hungry for success,” he says. “We didn’t fear anything. But the club went and bought too many players we didn’t need. We had six strikers at one point. They were spending all wrong.”

Burns, on the other hand, is more reflective. Now that Leeds have finally returned to the Premier League, he feels a more revisionist approach is called for when assessing the club’s demise.

“There’s always gambling from club hierarchies when you’re trying to stay at the top,” says the Australian, who now holds a directors role at Australian side Perth Glory. “We considered ourselves a genuine top-three side in the Premier League. We believed we belonged in the Champions League.”

“It’s inevitable, it’s how things work. You need to give yourself a chance.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments