The Last Word: A real World Cup tragedy

Once a Nigerian hero, Rashidi Yekini’s fate symbolises the cruelty and cheapness of life once celebrity fades and the cash runs out

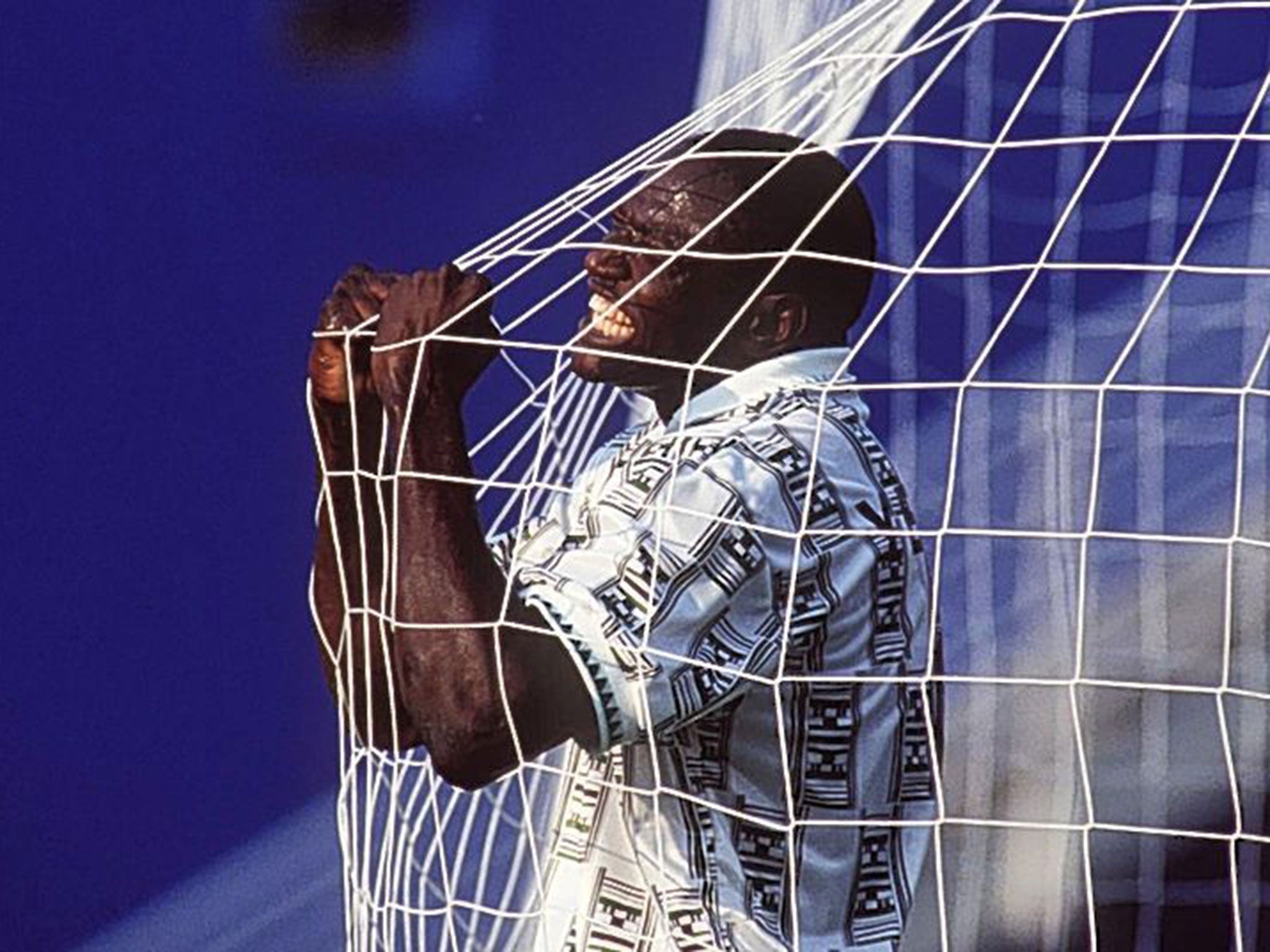

It is an iconic football image. Rashidi Yekini has just scored Nigeria’s first goal in World Cup history. He thrusts his hands through the back of the net and extends them in an evangelical pose, before recoiling and twisting the strings around his fingers. He is in tears, unintelligible. His team-mates are so unnerved by his primal scream no-one approaches him.

That was 20 years ago yesterday, in the 21st minute of a 3-0 win over Bulgaria in Dallas. In another unforgettable image, Yekini’s body is swathed in a white shroud, covered by a pink sheet. A green-and-white football has been placed beside his head. There will be no post-mortem, only enduring rumours he died of heart failure, while chained to the floor, on 4 May, 2012. He was 48.

There are few fairytales in African football. Since it is the continent on which it is closest to being the people’s game, it is poignant that it so often enshrines human fallibility. Corruption is institutionalised. Progress is prevented by inherently poor organisation, persistent political instability and chronic financial mismanagement.

In the 17 years since Pele’s infamously flawed prediction that an African nation would win the World Cup by the end of the 20th century, Senegal, in 2002, and Ghana, in 2010, have emulated Cameroon’s breakthrough in 1990 by reaching the quarter-finals.

Only Ivory Coast appear to have a realistic chance of doing so in this tournament, in which Cameroon, a squabbling rabble, have been branded a national disgrace. The Ivorians must do so under the pall of the unexpected death of Ibrahim Touré, younger brother of Kolo and Yaya.

Yekini’s goal helped to generate the illusion that Nigeria, the continent’s most populous country, would become its first global superpower. They became African champions last year, for the first time since Yekini’s goals steered them to the Cup of Nations title in 1994, despite the system.

Their manager, Stephen Keshi, Yekini’s former team-mate, worked unpaid for seven months because the Nigerian Football Federation pleaded poverty. His squad refused to board a plane to Brazil until a protracted bonus dispute was settled, the Federation securing a loan on the guarantee of $8 million (£4.7m) prize money from the finals.

Yekini’s fate symbolises the cruelty and cheapness of life once celebrity fades and the cash runs out. He secured a lucrative transfer from Vitoria Setubal in Portugal to Olympiakos in Greece on the strength of his impact in the US, but subsequent moves to Spain, Switzerland, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia and the Ivory Coast left him trapped in a cycle of decline.

It deepened in 2005, when a comeback attempt in Nigeria collapsed. He never received the promised mansion for his World Cup exploits, but lived in a large house in the town of Ibadan, through which peacocks strutted. He became a recluse, stigmatised by accusations he was mentally unstable.

Friends tell a contrasting story of a kind man who suffered from severe depression, or Bi-polar disorder. He would fire up a generator in his compound to watch Champions League matches, but felt compelled to take out a restraining order on his family, who were alarmed by reports he had burned his possessions and given money to the poor.

Neighbours reported that a group, allegedly led by his mother and the second of his three wives, kidknapped him as he attempted to gain entry to his house. Bundled into the back of a van, he was never seen alive in public again after being taken to a traditional healing centre.

Questions remain, and no one seems inclined to provide cogent answers. The hope he once represented has been smothered. He is a human tragedy, a footnote in football history.

If not Hodgson, who?

If only everything in life was as predictable as an England World Cup inquest. When personalities as diverse as John Terry, Wayne Rooney and Gareth Southgate are cast as saviours, requisite levels of random behaviour are being reached.

Calls for Roy Hodgson to resign are inevitable and justifiable since his innate conservatism re-emerged under pressure, but miss the point. He has no natural successor beyond Gary Neville, who must be tempted to accept a lucrative sinecure in TV punditry.

Suggestions that St George’s Park will produce a new generation of managers are naïve nonsense, given such foreign nonentities as Jose Riga and Beppe Sannino occupy the sort of Championship jobs which would accelerate the development of home-grown coaches.

Forget the Premier League as an employment bureau. Brendan Rodgers has the emotional intelligence and tactical sophistication to become a hugely successful international manager, but is understandably consumed by the challenge of restoring Liverpool.

Don’t expect anything remotely creative from the Football Association. They may preach modern methods, and profess to believe in a culture of marginal gains, but have no real concept of progress beyond keeping Wembley full with a series of increasingly desperate marketing campaigns.

All that’s missing is the moral outrage when England players are captured on holiday in seven-star luxury. Richard Scudamore is innocent, OK?

Trott is back but needs time

The headlines spoke of failure, a seven-ball struggle for a single run. Warwickshire may have omitted to mention Jonathan Trott was making a first-team comeback on Thursday evening, but they could not avoid the fall-out.

Trott improved the following evening, scoring 39 in a defeat by Worcestershire. He will continue to be dogged by premature expectation but deserves time and understanding to overcome his most significant opponent, himself.

Racing is going off the rails

Television ratings are plummeting. Leading jockeys are anonymous. Bookmakers wield undue influence. Morning suits might have been de rigueur at Royal Ascot, but funeral threads were more appropriate. Horse racing is in more trouble than it appears to realise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments