The force that was above the law

South Yorkshire Police lied and smeared in their desperation to cover their backs – just as they did during the miners' strike

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

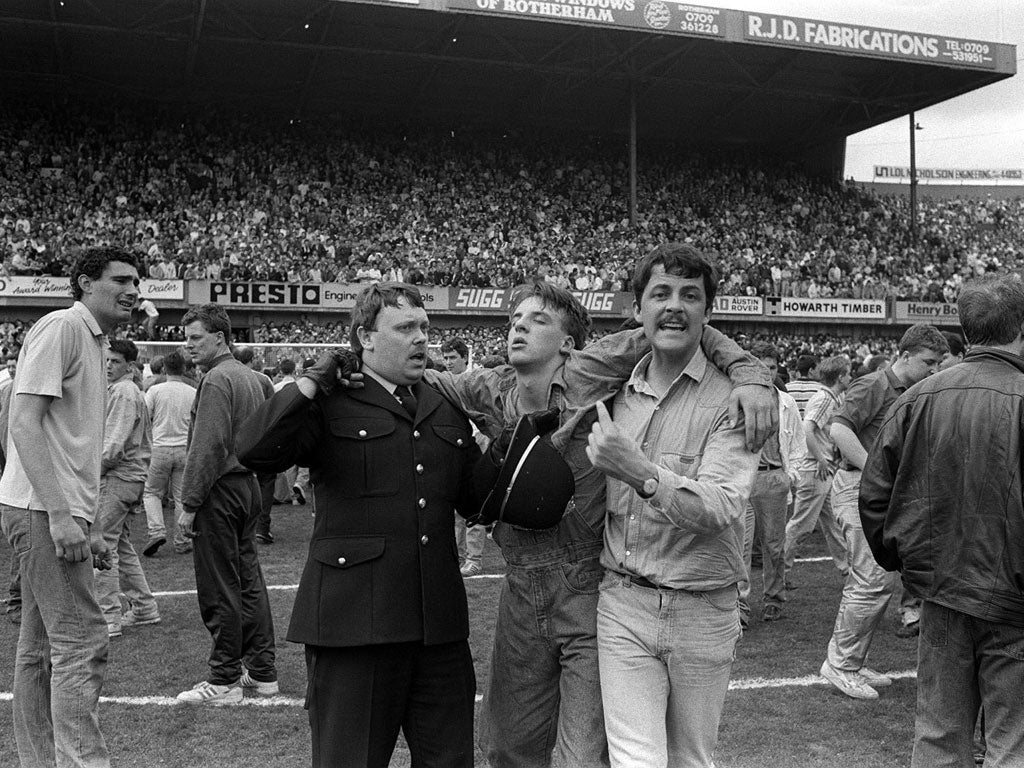

Your support makes all the difference.The first recorded lie told by a police officer after the Hillsborough disaster was at approximately 3.15pm on 15 April 1989, 10 minutes after the game had been stopped, and at a time when, as we now know, 41 of the day's 96 fatal casualties were still alive and might have been saved. It was around that time that Graham Kelly, chief executive of the Football Association, called the control room at the Hillsborough ground wanting to know what had caused the carnage on the terraces.

The man in charge of the police operation, Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield, responded with a bare-faced deception. He told Mr Kelly that Liverpool fans arriving late for the game had forced a gate open at the Leppings Lane end of the stadium. Ch Supt Duckenfield knew very well that from 2.45pm onwards he had been called on the telephone three times by an increasingly desperate officer on the ground, who warned that trouble was developing as 5,000 supporters were trying to get in through 12 turnstiles.

After the third call, he ordered his men to open the gate that he later accused the fans of having forced open. It did not occur to him to warn officers inside the grounds that they were going to have a sudden rush of 5,000 impatient supporters, who would need to be directed to where there was space for them. Undirected, they poured along the nearest tunnels into pens three and four, which were already full.

Where Ch Supt Duckenfield led, other officers followed. That evening, a journalist working for Whites Press Agency in Sheffield bumped into a senior police officer whom he had known "for many years" – according to the memo the agency later compiled, published this week.

The officer volunteered the information that he had been "punched and urinated on" as he was trying to save a dying victim. The next day, the same journalist met another officer who, unprompted, claimed to have seen fans attacking or urinating on the police.

On Monday, two days after the tragedy, another reporter from the same agency met a third officer who told him that fans were urinating down the terraces as the police pulled away the dead and injured. The agency then put together the report which was picked up by The Sun, producing that now infamous headline "The truth". Other newspapers also used the report, though not with the same uncritical brashness.

Even after it was obvious how much distress and anger stories like these were causing on Merseyside, Paul Middup, a spokesman for the Police Federation, told the Daily Mail: "I am sick of hearing how good the crowd were. Just because they weren't tearing each other's throats out doesn't mean they were well-behaved. They were arriving tanked-up on drink, and the situation faced by officers trying to control them was quite simply terrifying." The fans, he said, "were diving under the bellies of the horses and between their legs, and the only people who do that are either mental or have been drinking very heavily".

These stories suggest several things. The senior officers who spun them must have learnt to despise the working-class spectators who filled the football terraces, particularly if they had Liverpool accents. This contempt was apparently felt intensely in the higher ranks. When Lord Taylor reported on the disaster a year after it took place, he complained that while the constables he interviewed were "intelligent and open" the senior officers were "defensive and evasive".

More seriously, it suggests a sense of invulnerability and infallibility at the top of the force, as if some within the senior ranks believed they could do no wrong and when faced with the consequences of their own mistakes, they lied and blamed others. The former Labour Home Secretary, Jack Straw, believed that this mindset arose from the industrial strife of the 1980s, particularly the 1984-5 miners' strike. "The Thatcher government, because they needed the police to be a partisan force, particularly for the miner strikes and other industrial troubles, created a culture of impunity," he said yesterday.

South Yorkshire Police, the force that was on duty at Hillsborough, also policed the mass pickets outside the Orgreave coke works in May and June 1984. They claimed to have been attacked by the miners, 95 of whom were charged with riot and unlawful assembly, only to be acquitted after their defence lawyers accused the police of fabricating evidence. At other times, the collapse of a trial amid allegations of police fabricating evidence would have been a national scandal, but this one produced only a muted response.

Meanwhile, there was another case that had been festering throughout the decade. For years, there had been doubts about the convictions of people accused of involvement in the bombing campaign which the IRA carried out in London and Birmingham in 1974. They had been convicted because courts and juries trusted the evidence given by the police.

When one case went to appeal in 1980, the Master of the Rolls, Lord Denning, stopped it, saying "If they won, it would mean that the police were guilty of perjury… That was such an appalling vista that every sensible person would say it cannot be right that these actions should go any further."

By the end of the decade, that "appalling vista" was becoming hard fact. Douglas Hurd, the Home Secretary who received the police reports into the Hillsborough disaster, was also the first to come face to face with the possibility that police might lie to incriminate the innocent. He ordered a new inquiry into the case of three men and a woman convicted of planning an IRA bomb in a pub in Guildford in 1974.

They were set free in 1989, after 15 years in prison, amid a blaze of publicity which told the country that there are occasions when police officers will tamper with evidence and lie. It took a very long time to find out the full extent to which they lied about the victims of the Hillsborough disaster.