Why south London is turning out so many great footballers

While Sancho and Gomez are the stars of this year, they are not the end of the story, says Jack Pitt-Brooke

Look at the team at the top of the Premier League. Or the team on top of the Bundesliga. Or the England team. Or any England youth teams. Or any youth teams from any of the Premier League’s top sides, not just in London but increasingly in Manchester and Liverpool too. You will see the same stamp: young English players playing with flair, with freedom, showing the skills that they taught themselves and their friends. The football of south London, played for the best teams in the world.

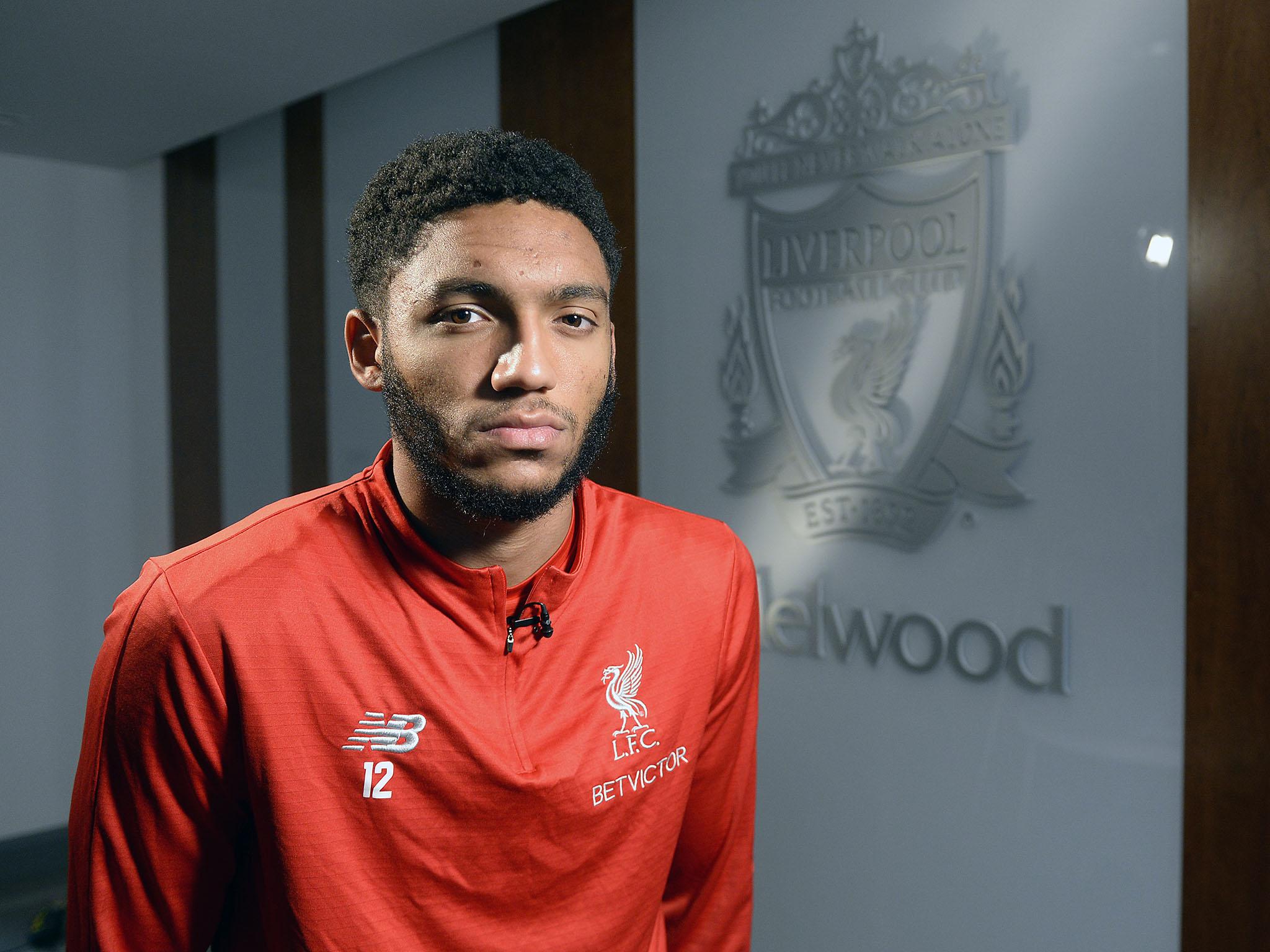

No English players have been more exciting in 2018 than Jadon Sancho or Joe Gomez. No one promises more for 2019, in the Champions League, the Nations League, or in Euro 2020, than they do. But what about Reiss Nelson, starring in Germany and for England Under-21s? Or Ademola Lookman, starting to make himself heard at Everton? Or any number of talented youngsters increasingly visible across our national game, all from the adjacent boroughs of Southwark and Lewisham.

This small band of dense city, just a few miles across, is now one of the productive hotbeds for young footballers anywhere in the world. Other parts of the country have been able to claim this before: Huyton, Wearside, more recently Barking in east London. But south London is now on top. It can claim to be England’s own version of the Paris banlieues, the greatest talent factory in the world.

This is not some fresh discovery. There have been great footballers of the past generation from this same corner of London: Ian Wright, David Rocastle, Rio Ferdinand. But now we are seeing the flourishing of the next generation. And the goldrush of scouts and agents to the area to take advantage, and the scattering of these players all over the country. Football is changing, and so are the type of footballers teams wants on the pitch.

* * *

It all starts with mastery with the ball. Speak to those who spend their lives combing through London for the best young players and they will say that the first thing they want is elite technical quality. But that is what you can find among a generation of boys whose lives revolve around football.

Urban areas this densely populated force children to be creative to find their playing space, using any car park or yard or cage that they can use. The lack of green space forces them to play smaller games, on smaller pitches. But that is no bad thing, especially when they are learning how to control the ball, how to run with it, how to use both feet and how to beat an opponent even in the tightest space.

That was the story with Jadon Sancho and Reiss Nelson in their early years, mastering the ball in the cramped confines of their south London estates. Sancho grew up in the Guinness Trust Buildings, a tenement block built in 1921 round the corner from Kennington Tube station. Nelson is from the nearby Aylesbury Estate in Walworth, just off the Old Kent Road. As soon as they could they were playing football on local concrete courts and cages, in one of the most built-up parts of the country.

And so when Sancho and Nelson arrived for an early taste of organised football, representing Southwark in the London Youth Games, they immediately stood out ahead of the rest. They would train on the astroturf on nearby Burgess Park – the park where Rio Ferdinand had learned the game one generation before – and when that was booked, on the cricket pitch instead.

But coach Ahmet Akdag was overawed when he first saw these two even at the age of nine. All of that work had massively paid off. “They were both very sharp with their mind and with their feet,” he says. “Just on another level from any of the others. It was that ability to glide past players like they weren’t there. The ability to play off both feet. The speed on the ball, the speed of thought. The skills to beat players just as quick as them, because they were steps ahead.”

It’s about creating the right environment. So they can learn and develop, and be confident enough to express themselves

The priority for the coaches was never to change the natural game of Sancho and Nelson, but to provide them a platform on which to express themselves. “It’s all about creating the right environment,” said Akdag, who now runs Cre8 Football in Selhurst. “So they can learn and develop, and be confident enough to express themselves.” And it worked: Sancho and Nelson’s team won the London Youth Games in 2011.

By that point the pair were already playing football the same way they play football now. With a style that is itself distinctly of south London football: imaginative, risky, daring, determined to beat their man in a way he cannot predict, never mind stop. Some might call it showy or even performative but in an English game that has traditionally been predictable, rigid and stale – two banks of four, second balls and set pieces – these are the players that get people excited.

No one knows more about the culture of south London football than Gavin Rose, the manager of Dulwich Hamlet, and founder of the local Aspire Academy. He has spent his life working with young players from this area, helping them into the non-league and professional game. For him, that south London football identity produces players with their own distinct style. “There is a culture in south London, that the player who has flair and takes risks with the ball is seen as a good player,” he says. “It’s an unspoken thing, where young lads in south London are encouraged to take risks and do the unpredictable thing. They try things off the cuff, they’re not textbook players.”

* * *

Elite technical ability is only half the story. The other half is mental. And speak to those who have known Sancho the longest and the words they keep using are “hunger”, “bravery” and “fearlessness”. And they point to that upbringing in Southwark, one of London’s most deprived and unequal boroughs, as fundamental to that.

There is nothing new about the best footballers growing out of difficult circumstances. That has been the case all over the world. Motivations are sharper, stakes are higher and children have to learn things early on that the middle classes can live their whole lives without having to know.

There are 32 London boroughs and, according to the Trust for London, only seven have a higher poverty rate than Southwark does (31 per cent), only six suffer from worse pay inequality, only five have a worse child poverty rate (36.68 per cent) and only three have a worse adult unemployment rate (6.5 per cent). Southwark is also the epicentre of London’s violent crime problems: in 2017-18 there were more knife crime offences there (860) than there were in any other London borough.

This is the context, if not the daily experience, for many of the youngsters who have grown up here and have found football to be their best way out. Sancho himself has spoken eloquently about how the reality of his childhood gave him that hunger to be a footballer. “Life would not have been too good for me because there were a lot of bad people,” he told the BBC recently. “What might have happened if I hadn’t is with me all the time.”

That fear of being sucked into the spiral of crime can be a motivator to focus on football. “Knife crime and gangs can help a talented footballer to stay focused,” says Dulwich manager Rose. “It can be a lure in a negative sense, but it can also be a lure in a positive sense. If you’ve got talent, you’ve got a way out, a way of not getting involved. They’ve all got mates who’ve been stabbed, killed, gone to prison, and that is a massive motivation to do well for themselves.”

This background often serves to provide local players with an extra edge over their counterparts from elsewhere. David Powderly is an FA elite coach, who is from south London, and works with some of England’s best players at under-16 level. “They are streetwise boys, they have to grow up quickly,” he says. “Not just because of the trouble, but even just to take multiple transports across London to get to training. Nothing comes too easily, but that gives you that desire.”

That was the desire that Sancho and Nelson, and plenty of others like them, have shown throughout their careers. It was immediately clear to their coaches that they had an extra edge on the other boys. “Jadon and Reiss not only show character in terms of their desire and bravery,” Akdag remembers, “they showed inner strength, and they were never satisfied with what they were doing.”

The nature of the football industry means that Sancho had to start making career decisions very young. But those decisions have all been marked by the same hard-nosed ambition to be the best he can be. Arsenal and Chelsea both wanted Sancho and he could have gone there easily enough. But he chose to go to Watford, eventually moving to stay in their boarding school Harefield Academy rather than commuting. Because he knew that he needed to get out of south London, away from his surroundings, to focus on his football elsewhere.

Soon enough Sancho picked up the attention of Manchester City, already on the lookout for the best of London talent. He had two impressive years before, in the summer of 2017, making the biggest decision of his life. City offered him more than £30,000 per week, the biggest contract ever offered to a 17-year-old. But he was brave enough to say no, and to leave for Borussia Dortmund. Those who know Sancho say it was about standing up for himself, and being his own man.

The following year, eight years after they played together for Southwark, Sancho’s best friend Reiss Nelson also decided to go to Germany to further his career, on loan at Hoffenheim, showing that same bravery that had been part of him his whole life.

* * *

The first time Joe Gomez was compared to Bobby Moore, he was still a 13-year-old playing at Catford Pits. That is a complex of pitches, near where Gomez is from, not in Southwark but in neighbouring Lewisham. For years it was where players from far outside Lewisham would descend every Sunday to play small-sided games and to test themselves against everyone else. It was a hugely important part of community life and locals mourn the fact that it has now been bought by a private school, restricting public access to it.

The rise of Gomez to being the starting centre-back at the current Premier League leaders, and of the England team, is all the more impressive given that he is still just a 21-year-old centre-back burdened with heavy responsibility. It prompts the question: what needs to be done to an unpolished diamond discovered in southeast London to turn him into a professional at the top of the game? And the answer, according to those who know it best, is not as much as you might think.

Gomez’s organised football started off with AC Paulista from the age of six, where he was fortunate enough to play for a coach who wanted to encourage the boys to enjoy their football, rather than coaching them too much. “Being able to play is the most important thing, I didn’t want too much adult intervention,” says coach Darren Smith. “I don’t like an environment of screaming adults. We are always telling kids what to do – shoot, pass, clear it – what happened to kids making their own decisions?”

Soon enough Gomez started to stand out for all the things we know him for now. “He just always wanted to play with a smile on his face,” Smith remembers. “All we could do was encourage and his parents were so supportive of what we were trying to do.”

We want them to play with the feeling on the pitch as if they were on the park

Gomez soon won a place to represent Lewisham in the London Youth Games, in a team coached by Andy Ansah, who remembered just how impressive the young Gomez was. “As a young lad he was quite quiet, but very astute and aware of what he needed to do on a football pitch,” Ansah says. “You could rely on him to do his job, to hold the team together. You knew he was going to be a top player, his attitude was spot-on. He was always going to make it.” Lewisham won the Youth Games with Gomez in their team.

Charlton Athletic soon picked Gomez up and even from the age of 12 local scouts believed that he had absolutely everything needed to make it, that they had never seen a defender as complete as him. And in his unflappability and his single-mindedness he reminded one observer of Bobby Moore, a comparison he has been stuck with ever since. By the age of 14 he was already playing for Charlton Under-18s. And, according to one of Gomez’s most influential mentors, he did not need much coaching, simply to be taught a system of play.

This is why the comparison with Rio Ferdinand is so instructive. He was not a traditional English centre-back either, but was far better at using the ball and at defending one against one than more textbook defenders. And coaches realised, as they did with Ferdinand, that they would gain more by adding to his natural game rather than taking anything away. When you discover diamond players, why hone away what makes them special?

This was what Charlton realised with Gomez’s team-mate Ademola Lookman. He was signed at the age of 16 after he scored four goals – two with his left, two with his right – for a London FA side in a friendly against Charlton Under-16s. He had only played Sunday league football until then, and so he arrived with an unusual rawness. Charlton knew this was a blessing, not a curse. “We were very conscious not to knock out that innate talent, that love for the football, out of him,” Charlton academy manager Steve Avory told The Independent last year.

Those who know Lookman see that same confidence in taking on opponents that he used to show for his Sunday league side in his game today, whether for Everton, RB Leipzig or England Under-21s. The same is true of Sancho and Nelson, who have taken the same skills and flair and confidence they showed in Burgess Park into the biggest competitions in the world. “It’s not about making a Sancho or Nelson,” Powderly says. “It’s about providing the environment so that they can flourish. Because we want them to play with the feeling on the pitch as if they were on the park with friends.”

* * *

There is a saying among the young footballers of south London: “we rise by lifting others”. And even though professional football is a cut-throat industry, the sense of community and solidarity among players from this area is part of the story too.

It used to be that black players from south London would often get overlooked even by their local clubs. The success stories were the exceptions but not the rule. But Ian Wright is still dedicated now to mentoring young black players in London to help them follow in his path. And each new success story only encourages more. Every single player that makes it feels a sense of obligation to the community to help the next generation, to keep coming back to matches at his old clubs. And every talented youngster will know someone, from their area or school, who has made it before them.

When Gomez was on his way up at Charlton, in February 2014, his team played a famous FA Youth Cup fifth-round game against Arsenal, at Ebbsfleet United’s ground in Kent. Up against the Arsenal of Alex Iwobi, Chuba Akpom and Ainsley Maitland-Niles, a 16-year-old Gomez was almost perfect before Charlton went down to two late goals. Legend has it that south London emptied of school children that day, so many jumped on the train to watch the teenager they wanted to follow.

Reiss Nelson went to London Nautical school in Lambeth, and his success in the Arsenal academy encouraged the boys younger than him to believe in themselves too. One of those boys was Vontae Daley-Campbell, the 17-year-old currently impressing on Arsenal’s FA Youth Cup run. The next generation of schoolboys will be inspired by Daley-Campbell’s successes, believing that they too can follow the same path.

Because while Gomez and Sancho are the stars of this year, they are not the end of the story. There are plenty more just as talented as them, following the same pathways. If not from Southwark and Lewisham then from Lambeth or Croydon instead. Like Arsenal’s Emile Smith-Rowe or Eddie Nketiah. Or Chelsea’s Tammy Abraham, Callum Hudson-Odoi or Trevoh Chalobah. Or Queens Park Rangers’ Ebere Eze, from Greenwich, one of the best young English players in the Championship.

This is no longer a London story. The Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP) means that Category 1 academies can go looking around the country for young talent. And no club has realised the potential of south London better than Manchester City. Sancho has been and gone now, but he is not the last. City signed Ian Carlo Poveda, part of the same Southwark team along with Sancho and Nelson, from Brentford in 2016. He is starring for City’s academy teams this year. Last month they bought Millwall’s 14-year-old Darko Gyabi, who is from Lewisham. Yeboah Amankwah, their young centre-back, did not even have a professional club when City plucked him from Sunday league football. Everton, Liverpool and Manchester United are trying to catch up.

Go to any Category 2 academy in London now and there will be scouts from all the big northern clubs, determined to find the next stars. The old racist stereotypes about whether black Londoners could cut it far away from home have been eroded into dust. Teams want English players and they want exciting players too. Players brought up in the challenging skill-based environments of Catford, Peckham and Croydon. The talent has always been there. But football has just woken up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks