Ray Wilson dead: England World Cup winner and one of the finest left-backs of his generation

A study in nimble poise and calm concentration, Wilson exuded style and efficiency, and although he shunned the limelight off the field, on it his voice could be heard constantly

By common consent England World Cup winner Ray Wilson was the finest British left-back of his generation, and there are plenty of astute judges who contend that, in his 1960s prime, he had no equal anywhere around the globe.

A study in nimble poise and calm concentration, Wilson exuded style and efficiency in equal measure, and although he shunned the limelight off the field, on it his voice could be heard constantly, his presence both ebullient and gritty. Above all, he was a team man to the core of his being, one who would never flinch at the moment of pressure.

Ramon Wilson, who was named after pre-war film star and singer Ramon Novarro, was the son of a Derbyshire miner who had been forced to quit the pit through serious injury.

Wilson’s parents had separated during his childhood and his mother died when he was 16. The upbringing was tough and frugal, there was no money for fripperies and he had no toys, but he wasn’t bothered as long as he had a football.

Always a gifted sportsman, he was imbued with a burning need to win at everything, but although he was invariably the star performer in lunchtime kickabouts, his games master refused to pick him for the school team on the grounds that he was too small.

However, justice was done when the teacher was off ill, selection was left to the boys and Wilson was allotted a place on the left wing. He shone and thereafter thrived in local junior football, playing for East Derbyshire Boys, then Shirebrook Victoria and Langwith Junction, eventually earning a trial with Huddersfield Town.

By then circumstances had made him a hard-headed and self-sufficient teenager, and being no academic he had left school at 15, working first as a wagon-repairer, then an engine-cleaner in a railway yard at Shirebrook, near Mansfield.

But when Huddersfield, mightily impressed at the way the diminutive youngster had dealt with a hulking opponent during the trial, offered him a place on their ground staff at a wage of £5 per week, he took the gamble of ditching his railway job, which paid twice as much, to tilt at the windmill of professional football.

However, his enlistment at Leeds Road in May 1952 did not bring rapid advancement. After signing as an apprentice, he spent more time sweeping, cleaning and painting the ground than playing the game and, having failed to make a mark both as an inside-forward and a wing-half, he became despondent at his lack of early progress.

Having spent two years at the club without as much as a reserve outing, and with National Service looming, he even contemplated coal-mining – which he had always abhorred, due to his father’s gruesome experience – as a long-term future, partly because it would secure deferment from joining the Army.

That plan failed because he had left it too late, so he spent two years, including a stint in Egypt, with the Royal Corps of Signals, after which his fortunes took a dramatic turn for the better when the shrewd Huddersfield manager, Andy Beattie, offered him a first-team debut at left-back, against Manchester United at Old Trafford.

It was October 1955, with United’s Busby Babes on their way to becoming champions and Huddersfield struggling desperately near the foot of the First Division, but although the Terriers duly lost, Wilson performed capably enough against England winger Johnny Berry to make it clear that finally he had found his best position.

Relegation followed, and Wilson did not gain a regular place until 1957-58, but then, despite suffering a succession of injuries, he blossomed under inspirational new boss Bill Shankly – the man destined to transform Liverpool from chronic under-achievers to one of the mightiest powers the game has known – relishing his role in an enterprising line-up which included the brilliant Scot Denis Law, who would later taste fame with both Manchester clubs.

Testimony to Wilson’s emerging excellence came with selection for the Football League against the Irish League in September 1959, and he was awarded his first full England cap against Scotland at Hampden Park in April 1960.

Such elevation was a massive achievement for a Second Division player, but after appearing to cement his international berth for the foreseeable future he was sidelined by knee damage and replaced by Mick McNeill of Middlesbrough, another high-attainer from outside the top flight.

Now Walter Winterbottom’s England went on a long unbeaten run, so it was not until McNeill, in turn, suffered injury in the run-up to the 1962 World Cup Finals in Chile that Wilson regained his role.

Meanwhile, not surprisingly, he was becoming disillusioned with Second Division life at Huddersfield. He had made protracted efforts to leave – Sheffield Wednesday had offered to buy him in 1959, since when more illustrious suitors had made enquiries – but his attempts had been frustrated, mainly because he was operating in the era of so-called soccer slavery, which gave clubs overwhelming power over their players.

In the early 1960s that iniquitously one-sided arrangement was swept away by a Jimmy Hill-inspired revolution, so when Wilson returned to Huddersfield after splendid displays during England’s progress to the quarter-finals of the Chile tournament, the climate for a move was much more favourable.

Keen to test himself at a higher club level and to earn more money, and perturbed by Huddersfield’s continuing mediocrity, he fell out bitterly with Eddie Boot, Shankly’s successor at Leeds Road, during contract negotiations, but it was not until July 1964 that he secured a transfer, to Everton in exchange for £35,000 plus Republic of Ireland international Mick Meagan.

As he was now approaching his 30th birthday he might have been daunted at stepping up a grade, and he struggled at first with the Merseysiders’ more rigorous fitness regime, then was hospitalised with a hip injury which kept him out for four months.

But Wilson was a thoroughbred performer with 30 England caps already to his credit, his reputation that of one of Europe’s finest, and soon his game, stimulated by the array of talent around him at Goodison Park, reached new heights. Wiry, compact and startlingly quick in short bursts, he was a tremendous all-round defender whose sound positional sense and assurance on the ball was matched by his courage in the tackle, and he settled seamlessly into a high-quality side containing the likes of visionary Scottish attacker Alex Young and commanding stopper Brian Labone.

That season proved to be the newcomer’s most successful in League competition, as the Toffees finished fourth, but in 1966 he helped to lift the FA Cup as Everton came from two down to beat Sheffield Wednesday 3-2 in an enthralling Wembley final.

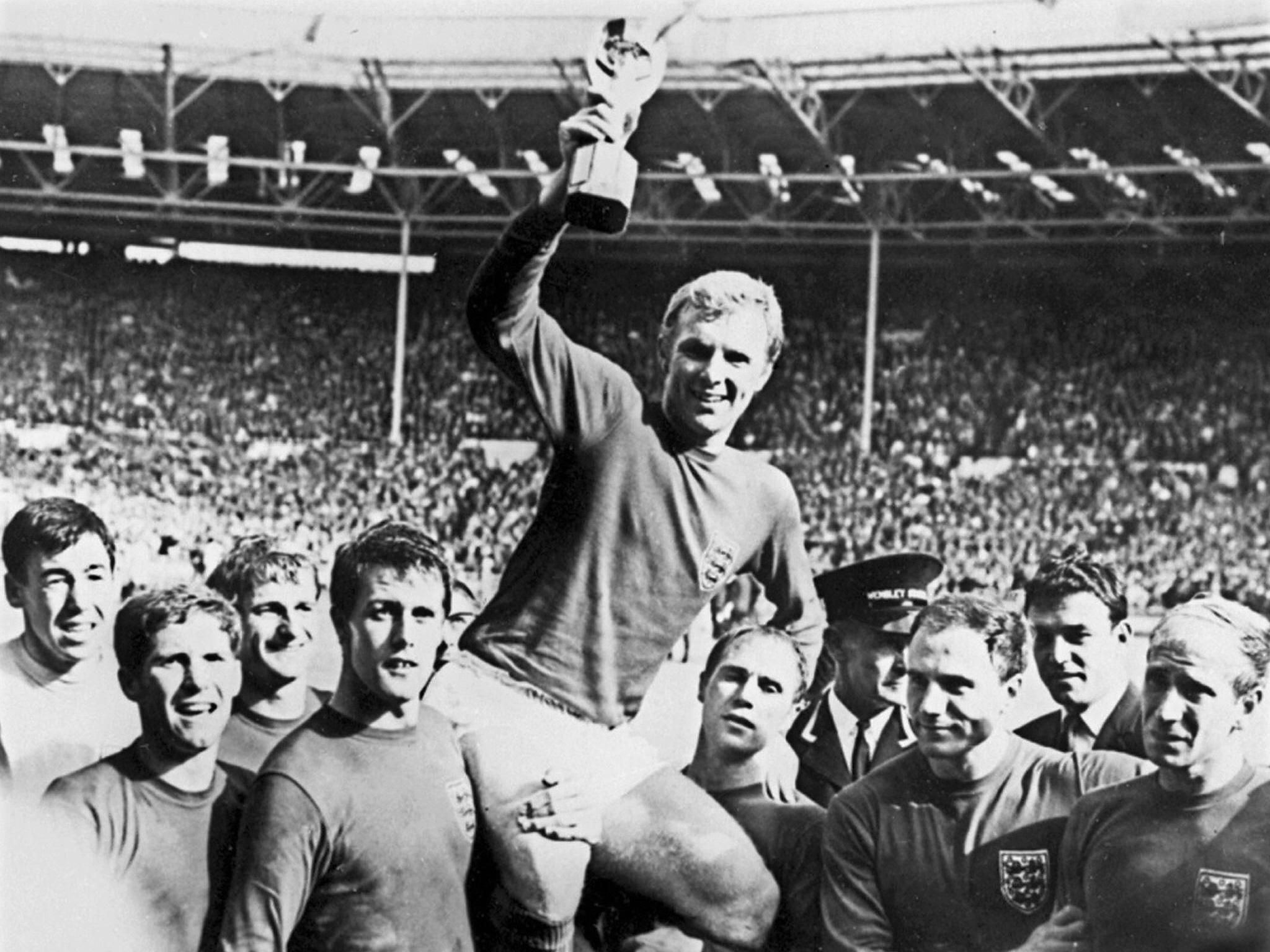

Ten weeks later, in that same stadium, Wilson was to experience a triumph which would dwarf even that, when Alf Ramsey’s England team confounded their many doubters by winning the World Cup.

After surviving a back scare during preparation for the tournament, he played in all six games, and was not seen to make a mistake until 12 minutes into the final when his uncharacteristically soft clearance, a veritable marshmallow of a header, fell to Helmut Haller, who gave West Germany the lead.

Typically unfazed by his blunder, he returned instantly to his customary impeccable standard, displaying perfect understanding with fellow full-back George Cohen – when one moved forward, the other held back to cover – and played a full part in securing a glorious 4-2 victory in extra time.

As the oldest player in the side at nearly 32, some observers expected him to make way now, but he remained a paragon of consistency and retained his England shirt until the third-place match against Russia in the 1968 European Championships. By then he was England’s most-capped full-back, with 63 appearances, a record later broken by Kenny Sansom.

Back at Everton Wilson reached another FA Cup Final, this time experiencing defeat by West Bromwich Albion against the run of play in 1968, but then twisted his knee during the following pre-season. His pace diminished and, deprived of that vital piece of his armoury, he was never the same again.

Thus in the summer of 1969 – just as Everton were about to kick off a term in which they would finish as champions – the man Goodison boss Harry Catterick described as the finest professional he had ever known was freed to join Oldham Athletic of the Fourth Division.

At Boundary Park Wilson was made club captain, but before long he was injured and he accepted the post of player-coach with Third Division Bradford City for 1970/71. Soon, though, his playing days were plainly done, he became caretaker manager at troubled Valley Parade, then was offered the job on a permanent basis, but he declined, relishing neither the responsibility nor the insecurity inherent in the position.

Instead he became an undertaker, joining his father-in-law’s business at Outlane, near Huddersfield, an occupation that suited his mordantly dry sense of humour.

When George Cohen was seriously ill, Wilson rang to offer his World Cup comrade a deal and to ask if it was true that Jews died standing up so the money didn’t fall out of their pockets. Cohen, who was delighted by the joke, recovered, and Wilson continued to ply his trade in relative obscurity, which he loved, with wife Pat and their two sons Russell and Neil.

His impact on Huddersfield was not forgotten though. The second-change kit for the 2016/17 season was released in his honour on 30th July – 50 years to the day after the World Cup triumph – while the Premier League game between the Terriers and Everton this April was recognised as Ray Wilson Day.

Ramon Wilson, footballer, born 17 December 1934, died 15 May 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks