James Lawton: The brilliance of 'United' was how it paid tribute to those who rebuilt the club

'I'm glad the film made the point that I have always believed – that but for Jimmy Murphy it could have been the end of United'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three years ago, Sir Alex Ferguson gathered his Manchester United players and told them it was the anniversary of a tragic event that happened in another age and on what might have been another planet.

Still, he thought it might be advantageous to their perspectives on football and life and, just possibly, to the level of emotion and commitment engendered the next time they pulled on their first-team shirts to get a little first-hand knowledge. He then introduced Sir Bobby Charlton, who mostly keeps the pain of what happened on the snowy airfield in Munich in February 1958 to himself.

It is probably impossible to overstate the extent of the ordeal this task represented for one of the last and the most famous of the Munich survivors – and maybe the relief he must have felt that Ferguson, as his team flew to Germany for tonight's Champions League semi-final first leg against Schalke, had a way of producing, if he cared to, a similarly inspiring effect without requiring him to revisit the worst days of his life.

The United manager merely had to order up some copies of Sunday night's brilliant – and essentially true – BBC dramatisation. There have been some negative reactions around Old Trafford but they should not deflect from an impressive reality. It is that the power of football to touch a city and a nation while it reflects some of the best of real life can rarely have been more graphically illuminated.

United unhelpfully muffed some basic details – Roger Byrne, not Mark Jones, was the pre-Munich captain, and then the armband was handed to the rugged ex-miner Bill Foulkes and not the brave but sometimes moody and erratic Harry Gregg, and if it was true the Yorkshire centre-half Jones liked to puff a pipe, he was never known to do it while running down to the field. However, unlike the extravagantly praised Damned United, the producers of United got something supremely right. They concluded that nothing could be more sensationally, or movingly, riveting than the large truth of the story.

This was that the responsibility for the survival of Manchester United fell upon the shoulders of the tough, hard-drinking No 2 Jimmy Murphy and that nothing in the history of the club – fashioned with such vision and hard brilliance by Sir Matt Busby – could ever obscure the value of the response he found among the remnants of arguably the most beautiful young team in the history of the game and the jumble of inexperienced and veteran players who were drafted into the crisis.

Nobby Stiles, a youth player sent home from the ground when the first news came in that there had been an accident in Munich the day after United had secured the 3-3 draw against Red Star in Belgrade which carried them into a second straight European Cup semi-final, did not see United.

He said he had missed it when reading his TV guide, a statement that did not dissipate entirely the suspicion that the emotions provoked might have been rated, 53 years on, nearly as draining for him as no doubt they would have been to his close friend Charlton.

Even so, Stiles is quick to separate himself from some of the fiercer Old Trafford reactions, which came most seriously over a somewhat unflattering, marginalising depiction of Busby, the man who eventually almost literally came back from the grave to continue his phenomenal life's work.

Stiles said: "I'm glad the film made the point that I have always believed – that but for Jimmy Murphy it could have been the end of United. He stood up and said that the club would not go down, despite suggestions of that coming from the board room – and he made sure this was so."

After leaving Old Trafford, numb and disbelieving, for his home in Collyhurst, Stiles changed buses in Manchester's Piccadilly, read an evening newspaper which, impossibly, carried pictures of his now-dead heroes, and finished up rocking with grief in the pew of his local church.

Stiles's father, Charlie, an undertaker, drove Murphy to all of the funerals, at some of which Stiles served as an altar-boy. Yesterday, Stiles underpinned the central theme of United, recalling how Busby returned after several months to Old Trafford physically shattered and with grief in his eyes but still able to raise the banner of hope that soon enough he would build another great team, this one containing Charlton, George Best, Denis Law and Stiles. That he would be able to do it, though, was unquestionably the gift of Murphy, the fine, tough West Brom and Wales player whom Busby was first drawn to in a wartime camp near Naples, where the Welshman was preparing an army team with impressive vigour.

"So Busby," recalled Stiles, "was always the symbol of hope and renewal. It was Murphy who held the line against submission to disaster. It was Murphy who reminded us of what we had been – and what we could be again."

And then there was Charlton, shaken to his bones by the catastrophe that he survived but would never forget; a young, sensitive man whose eyes had been opened to an unforgiving harshness of life he could never have imagined. The recovery of his nerve and spirit, confirmed when he interrupted his uncle's lunch-time pint in a North-east pub and asked him to drive him straight to Old Trafford, is the twin theme of United – and superbly realised.

The course and the impact of his experience is poignantly related in his autobiography. He says: "I will always see the path of my life as a miracle but in Munich in 1958 I learned that even miracles come at a price. Mine, until the day I die, is the tragedy which robbed me of so many of my dearest friends who happened to be team-mates – and so many of the certainties that had come to me, one as seamlessly as another, in my brief and largely untroubled life up until that moment.

"Even now, it still reaches down and touches me every day. Sometimes I feel it quite lightly, a mere brush stroke across an otherwise happy mood. Sometimes it engulfs me with a terrible regret and sadness – and guilt that I walked away and found so much. But whatever the severity of its presence, the Munich air crash is always there, always a factor that can never be discounted, never put down like some time-exhausted baggage."

Nothing is more heart-wrenching in United than the account of Duncan Edwards's losing battle and the emotion that besieged his great admirer and young friend Charlton when he found the nerve to walk up the hospital stairs to the ward where the hero of Old Trafford had staggered the German doctors with his resilience. "Where the bloody hell have you been?" Edwards wanted to know.

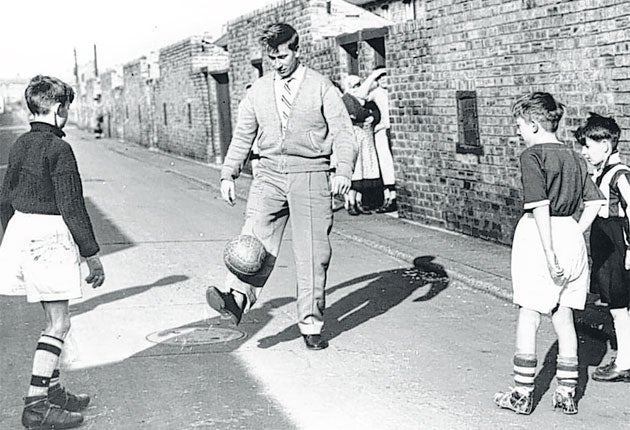

When, back in the North-east, Charlton was told that the great battle had been lost in Munich, there were times when he thought his love of football had died. But then he was drawn into the kickabout of some boys in the alley behind his parents' house and he thought of all the things that he had been taught by Jimmy Murphy.

He had taught him how to run and shoot in a way that liberated all his talent. He taught him how to run in the footsteps of Duncan Edwards. Now, maybe, it was time for the most important lesson of all – the one that tells you how to absorb the worst that life can offer, and then come back.

It would be uplifting to say that Jimmy Murphy's achievements were properly recognised by the successors to those directors who had advised him that the club should close down, but that would simply not be true.

His pension was hardly extravagant and he was pained to learn that the taxi account on which he travelled to Old Trafford had suddenly been cancelled. But then Jimmy Murphy always knew that football was a hard business.

Not the least of the achievements of United is that it explains how no one could have grown to know it better. He wept on the stairs of the Munich hospital – and then he went home to fight.

It is a story no one connected with Manchester United should ever tire of telling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments