James Lawton: Sneijder's brain power makes difference for sparkling Oranje

In added time there was a moment when all the logic of this game was put into the most severe peril

The superstars have failed in this 19th World Cup, we keep being told, but do not whisper it in the bars of old Amsterdam today and any time this side of Sunday's World Cup final.

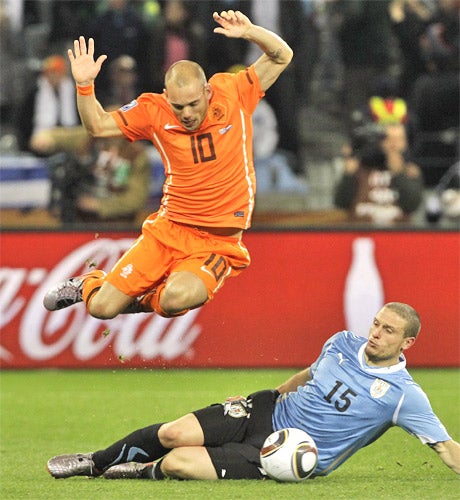

Here last night Wesley Sneijder and Arjen Robben defined quite what it was to go out and meet their responsibilities as footballers of vast reward and national following.

There were times when the Dutch were less than magisterial but they had something that will always remain utterly decisive. In Sneijder and Robben they had two players with the moral courage to accept responsibility for all that was happening around them. They played and they thought their way through any hint of crisis.

They broke down Uruguay and their hero Diego Forlan with a combination of craft and moments of brilliance which made their passage into the final entirely appropriate.

Between them they settled to the job of inflicting the quality of their talent and the depth of their understanding of how to win the big games.

Robben had moments of bewitching creativity but in the end it was Sneijder who wielded the most systematic influence, the most persistent intelligence.

Earlier the Dutch believed they already had the history, the football pedigree and the goal to light up their path to the World Cup final.

It was a reasonable assumption because Giovanni van Bronckhorst's strike would have graced any pinnacle of the game. He hit it perfectly from 40 yards and Uruguay's goalkeeper Fernando Muslera was a doomed figure flying through the air from the moment it left the veteran's boot.

What more did the Oranje need as they pursued the business left unfinished by their great predecessors in the finals of 1974 and '78? They had the inspiration of a goal from the heavens and had placed themselves back at the highest level of the tournament whose challenge has haunted them since the day Johan Cruyff's team failed to exploit fully the range of their astonishing talent.

They also had Sneijder, a Champions League notch on his belt already, justifying the growing belief that in this time of the wilting superstar he is a player offering the rare combination of high skill and the most severe football intellect.

His movement, his eye for anything like an opening in a Uruguayan defence forced out of its trenches by the Van Bronckhorst bolt, seemed to be inevitably carrying the Dutch to their third final – and possibly a historic rematch with their nemesis Germany.

The trouble was Uruguay carried a little bit of history of their own, more than a little pride and someone capable of scoring a goal to match the one of Van Bronckhorst. Forlan, whose impact for Uruguay had matched that of Sneijder on the way to this game, picked up a ball directly out of defence, turned and shot from nearly 30 yards. It meant that suddenly we had a match doing more than stirring the embers of history, but one with a distinct potential to make some of its own.

Indeed, the impetus provided by Forlan's superb strike had plainly given Uruguay a potent reminder of some the glories of their own past. They were, after all, doing more than merely striving to reach a final for the third time. A nation with a population of just three million was, astoundingly, just two wins away from a third triumph. It briefly seemed a little closer than that when Forlan again threatened Holland's goal, this time with a biting free-kick which required a desperate save by Maarten Stekelenburg.

However, the Dutch in the end had somewhat more urgency and rather more talent. Certainly, they had the men to win their first World Cup, and they stepped up to move closer to the ambition with goals that tore away Uruguay's resolve.

The goals came from Sneijder, Holland's supreme organiser and thinker, and Robben, a player who can be as luminous and as acute as he is sometimes exasperating.

They were not the result of mere bursts of virtuosity. They came from the Dutch ability to analyse, to probe and then, when their opponents are beginning to stumble, to go for the cleanest of kills. In this Sneijder was the quite relentless instigator.

It is true Uruguay struck back with nerve at the end and when they scored in added time through Maxi Pereira, there was a moment when all the logic of this game was put into the most severe peril. Uruguay had, not for the first time in their history, performed with honour – right up to the moment of the final whistle.

Then the pain of defeat enveloped them for a little while and they scuffled with their conquerors. It was a pity because this had grown into an absorbing match, with the best team claiming another date with football history.

HOLLAND'S FINALS...

1974: West Germany 2 Holland 1

The exponents of 'total football' took an early lead when Johan Cruyff won a second-minute penalty, which Johan Neeskens scored. The Dutch continued to dominate but couldn't score again and soon trailed to Paul Breitner's penalty and a typical close-range Gerd Müller strike.

1978: Argentina 3 Holland 1 (aet)

Dick Nanninga scored a late equaliser against the hosts in a hostile Estadio Monumental. Rob Rensenbrink hit the post in stoppage time, but a brilliant Mario Kempes goal – his second – put Argentina ahead in extra time, before Daniel Bertoni made sure.

Ollie Wright

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks