James Lawton: Old Trafford's two greatest men share one crucial characteristic: an undying yearning for victory

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

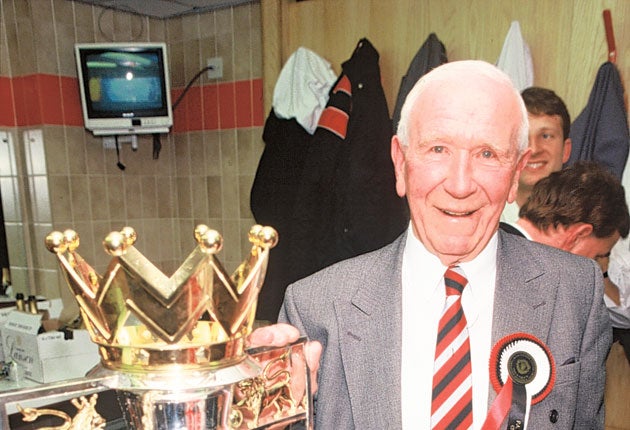

Your support makes all the difference.Some things history never gets quite right and the certainty of this at least will be confirmed again when Sir Alex Ferguson tomorrow at Stamford Bridge strides beyond his great predecessor Sir Matt Busby as the longest serving manager of Manchester United.

No one can quibble, of course, with the record of the days and the months and the years, or the fact that Ferguson long ago surpassed, at least in the mere accumulation of trophies, a man once described as the father not just of United but all of football. But we can say that the milestone Sir Alex now passes is also dressed in a massive misconception.

This is the one that says that in their style and their meaning Busby and Ferguson are linked only in their achievements and that as men they could scarcely have been more different.

It is simply not true. There are, no doubt, differences that can be scrawled in something no finer than crayon.

There is Busby the gently soothing diplomat, who remembered your name and used it in the most friendly manner whatever wrong you may have done him, and there is Ferguson, the born agitator who will doubtless carry a thousand hurts and grudges to his grave. There is Busby the kindly uncle and Ferguson the remorseless avenger scything down his enemies.

But then there is this other reality and one which, when you think about it, only makes sense when you consider what one man did and the other continues to do in pursuit of extraordinarily consistent success. It is that football has never known more ruthless, more obsessive men of ambition than Matt Busby and Alex Ferguson.

No men in football have ever been more jealous of their reputations or their ability to inflict their will.

No men in football have ever understood more clearly that there is only one relevant question to ask of any player prosecuting their day-in day-out ambition to win and that it is one that has to be stripped of the merest hint of sentiment.

History says that Ferguson has displayed the greater appetite, the more relentless ambition but at 68 he would be the first to say that Busby might have stayed on in the game far longer if the Munich tragedy had not come so close to breaking both his body and his spirit.

In fact, Busby never brushed failure in football more acutely than in his handling of the transfer of his power to a series of successors who, to greater and lesser extents, were traumatised in their attempts to walk in the great man's footsteps.

Wilf McGuinness, an ultimate Old Trafford zealot, lost his hair in the pain that followed the swift ending of his regime and Frank O'Farrell, who came with the most promising of reputations, complained bitterly of the all-pervading presence of the man who still occupied his old office who he believed had only superficially surrendered the reins of power.

O'Farrell, too, went quickly to the wall and later he wrote an unpublished book with the self-explanatory title, A Nice Day for an Execution. For different reasons, Tommy Docherty, Dave Sexton and Ron Atkinson all went the same way and it was not until the arrival of Ferguson that the "Old Man" relaxed in the belief that, sooner or later, the destiny he had so reluctantly bequeathed would be carried forward.

With the help of Sir Bobby Charlton, Busby protected the back of Ferguson in those perilous years when vital work was done in the rebuilding of the scouting system that brought forth Giggs and Scholes, Beckham and the Neville boys but time had to be bought. As the transition prospered the founding father who had long worn the sash of the highest honour bestowed by the Vatican on a Catholic layman, Knight Commander of the Order of St Gregory, could congratulate himself that an earlier award, the one of a paid-up street fighter of the game, had been entirely justified.

Busby's genius, as has been Ferguson's, was to get the best out of his players but we do not have to delve too deeply to know that if he regarded, genuinely, the fallen of Munich as lost sons for whom he would always bear a burden of responsibility, there was never any question about his highest priority.

It was the safekeeping of his club, his creation, and Nobby Stiles, one of his most diligent of servants, who as a United apprentice rocked with grief when the news came in from Munich, discovered it soon enough. The evidence came when Busby called him to his office and suggested he turned down a call from the new England manager Alf Ramsey because of a conflict with United's needs.

Stiles' recall of the conversation still carries a chill all these years later. "I couldn't sleep that night. I thrashed about thinking, 'Football shouldn't be as complicated as this." Partly through the urging of his young wife Kay, Stiles elected to take his chance with England and, as it turned out, claim a World Cup place. But it was not with the blessing of the Father of Football.

Stiles's brother-in-law John Giles never felt the glow of Sir Matt's patronage and was banished to Leeds United following a wage dispute involving less than £5 per week. Eventually, and after Giles had become one of the game's most influential midfielders, Busby conceded that it was possibly his greatest mistake in football – but a principle had been challenged and the result had been inevitable.

There is a pattern here and it is not so hard to trace. It builds around the central thrust of both Busby and Ferguson and it is about an understanding that if you have a plan, and a set of priorities, they cannot be disturbed by any notional sense of what is right or wrong.

Busby could hardly have disapproved more thoroughly of the errant, much publicised behaviour of his most gifted, and problematic recruit, George Best.

He knew the damage Best's lifestyle was causing to the image and discipline of the club but the judgment had come not in moral but practical terms. At what point did the problem of Best outweigh his dwindling value? It could be the only consideration and maybe now is it not unreasonable to read Ferguson for Busby and Wayne Rooney for Best?

You take the best and you live with the rest if it is for the benefit of Manchester United.

You also compress all your experience of life into what you are trying to achieve both for yourself and your football club and if both men proved faithful to nothing so much as their ambition, you do not have to look far for the origins of such attitudes.

Busby learned his in the pits and the strikes and the politics of Lanarkshire and when he also looked at the cost to his family of fighting a war imposed from above.

He was left fatherless by a sniper's bullet in the Battle of the Somme and beneath the gentlemanly image – he was remembered on Merseyside from his days as a Liverpool player as the most upright of commuters, a newspaper folded, immaculately tucked beneath the arm of a tweed jacket – we know there was a still smouldering anger.

Ferguson fought his early battles in the shipyards and the factories of Govan and what he learned there has always informed his work in football.

In the early days at Old Trafford he suffered terribly from the effects of a heavy defeat by Manchester City. He reported a desperate sense of guilt, of a failure of responsibility that haunts him when he thinks of those days when his place as Busby's heir was far from secured.

Perhaps here is the truest link between the men who made Manchester United: this ferocious need to prove that, whatever a result, you have given everything within your power.

When Busby died in 1994, soon after Ferguson had made United champions again, his coffin was borne past Old Trafford, where the streets were lined with people on a glum, rainy day. Charlton said: "When we looked at all the thousands of people crowding the streets we could see in their tears the meaning of the best that football can achieve. The Old Man always told us that football was more than a game. He said it had the power to bring happiness to ordinary people. In the sadness and the rain you had to believe that was the glory of his life."

Whatever is left for Alex Ferguson to achieve, he is surely entitled to a little of that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments