James Lawton: In a city divided by past and present Charlton proves constant who unites

"There was one constant in my football career. It was the vital life of Manchester"

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

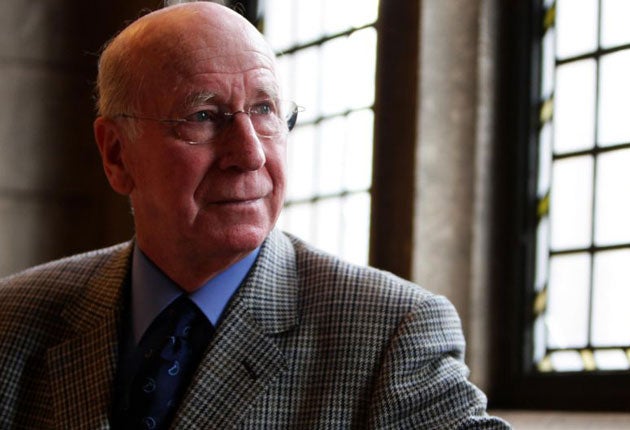

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Bobby Charlton was an apprehensive 15-year-old when he arrived in Manchester. He stepped off the train at Exchange Station in an ankle-length pea-green raincoat into which his mother Cissie had assured him he would one day grow.

She was right, and in more ways than any mother could reasonably imagine, and her boy was wrong to fear, as he stood amid the locomotive steam and winced at the sight of the grim, soot-stained buildings, that he might be overwhelmed by his new life and his new city.

The extent of that first miscalculation was made clear last night when Manchester symbolically and officially confirmed a reality of, roughly speaking, around 50 years, and gave him the freedom of the city.

There was still, inevitably, a hint of the shyness so apparent to the old ramrod of Manchester United, Jimmy Murphy, when he met the boy at the station, but it was impossible not to note at the civic ceremonials that if Bobby Charlton was still mystified by how much he had gained from a natural ability to play football consummately well, so much else had changed.

Most obviously, and immutably, is the idea that a footballer at such an early age would elect himself not only the hero of a city for his brilliance on the field but also as a tireless ambassador and advocate for all its endeavours as one of the great manufacturing centres of the world. This is not necessarily a criticism of today’s equivalent of the young Charlton.

It’s true that when Robinho signed for Manchester City last year he more or less admitted to being more interested in the colour and the extent of the money than where he happened to be earning it – and that the moment Cristiano Ronaldo established himself as the heart-throb of at least half of the city he made it clear he would rather be somewhere else.

No, you might yearn for the days of loyalty to a community, and when fans did not bark like Pavlovian dogs when one of their former players touched the ball, but not the iniquitous treatment of great entertainers like Charlton and, you name them, players like Matthews and Mannion and Finney, who despite filling stadiums across the land could hardly dream of the wages of a junior bank manager, and still less a profitable change of employment if it was not deemed to be in the interests of their clubs.

There are a hundred reasons why Bobby Charlton couldn’t happen today and one of them is that no one playing the game professionally is ever likely to have to serve a trade apprenticeship, as he did in a local factory, a chore that was initially made more difficult because of his lack of a watch that would have told him more precisely than the lightening sky over his digs when it was time to get out of bed and off towork.

So, given all this, the impulse last night was not to mourn old days, and complain about the different values of the ones that have replaced them, but simply to celebrate the exchange of affection and respect between one of our greatest sportsmen and most important cities.

No one has defined the strength of such a long-living relationship more emphatically than Charlton himself. He says, “In all the highs and the lows of the football career I was attempting tomake there was one constant character.

It was the vital life of the city which revealed itself to me a little more each day. The power and energy of Manchester pressed against the Old Trafford ground, reminding me always of that purpose of football to bring a little light to those who worked in the soot and the clanging noise.

“There were two huge black warehouses next to the ground and two enormous chimneys, one off-white and the other dark-coloured. One of the advantages of playing at home was that whenever you looked up you saw one of the chimneys and knew precisely where you were. Because the Cliff training ground was needed for junior matches, the pitch was not really good enough for the first team to work on, so sometimeswe trained on a field in the industrial landscape beside the Ship Canal – and when that was not available, we had another works pitch next to a smaller canal. The sounds of the factories were all around us and at the approach of lunch-time we knew what was on the canteen menu at the massive Metro-Vicks plant – you could smell the spotted dick or the rice pudding.

“Wherever you looked there was steam and smoke and industry. Nearby was Glovers, a factory which produced huge coils of cable which were carried across the canal on a pulley and then lowered into the ships which would take them all over the world, and then they would go under the sea.

It was exciting to see the power at work that generated the wealth of the city, and deep down I felt great pride that I was representing such a place on the football fields of England and, maybe soon, Europe.”

Charlton, like Sir Matt Busby, another man from a fierce, proud mining culture who seemed to slip so effortlessly in the heart and the spirit of his new city – is very attached to the great picture of L S Lowry, which depicts fans striding full of anticipation and optimism to The Match.

“Once,” recalls Charlton, “I saw a picture by my friend Harold Riley that moved me so much I bought it for a friend. The picture rekindled all the emotion which came to me when I used to look at that great scene of industry, with the prows of the ships poking into the dark and gritty sky framed by cranes and chimneys and those towering warehouses.

“When I first saw the Lowry picture it took my breath away. It seemed to capture all that I had seen and felt as a boy and then as a youth in the factory; it described the lives of theworkers and the lure of that patch of green at the football stadium.”

Such is the lost world once inhabited by a great footballer – and perhaps the reason why last night it came back to life long enough to give him its key.

Revealing truth about cheats on the track

There are many shocking sentences in the new autobiography by Dwain Chambers, but the one which transcends all others – and which rips the heart out the argument that drug cheats are almost invariably destined to achieve only the status of pariahs - screams from the page with an appalling weight of bitter truth.

It says: “I went a long time with no positive tests and if I hadn’t got sloppy we would still be doing it now.” Indeed, the Balco drug factory might still be churning out its products if a disaffected coach had not tipped off the authorities by mailing in a contaminated syringe.

The sound of Chambers’ voice maybe odious but it cannot be ignored. Not if the hope that elite athletes are clean is ever going to be more than a trembling prayer.

Athletics, no doubt, will choose to ignore Chambers’ tome. In the same way that it so religiously refuses to take a peek in the mirror.

Don’t play dumb and dumber, just keep shtum

If there is anything worse than seeing England’s rugby players troop off to the sin bin with the injured countenance of errant schoolboys, it is listening to them while they discuss their outrageous fate.

Mike Tindall set the standard after the weekend one-point slaughter by Ireland, saying, “I don’t think they did really much to earn the victory. They didn’t deserve to win the game, we gave them the game. You could say we gave Wales the game. We’ve to take it on the shoulders.”

How much better, though, if rather than take on their shoulders the extremely doubtful proposition that they are a few minor adjustments away from becoming a viable team, they acquire at least one head with the capacity to think its way out of a skullcap.

If you have proved, for a fourth successive Test, incapable of meeting basic professional demands, the least said the better, especially when you are saddled with the poignant illusion you are within several streets of teams of utterly superior quality.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments