Jack Charlton: Four words and an honorary Irishman who changed the way a nation was viewed on a global scale

Charlton’s 10 years in charge of the Irish national team helped to change history on a scale wider than just a sporting sense and strengthened relations between the two nations at a time of great difficulty

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was four little words that did it, and brought tears of joy to Jack Charlton’s eyes.

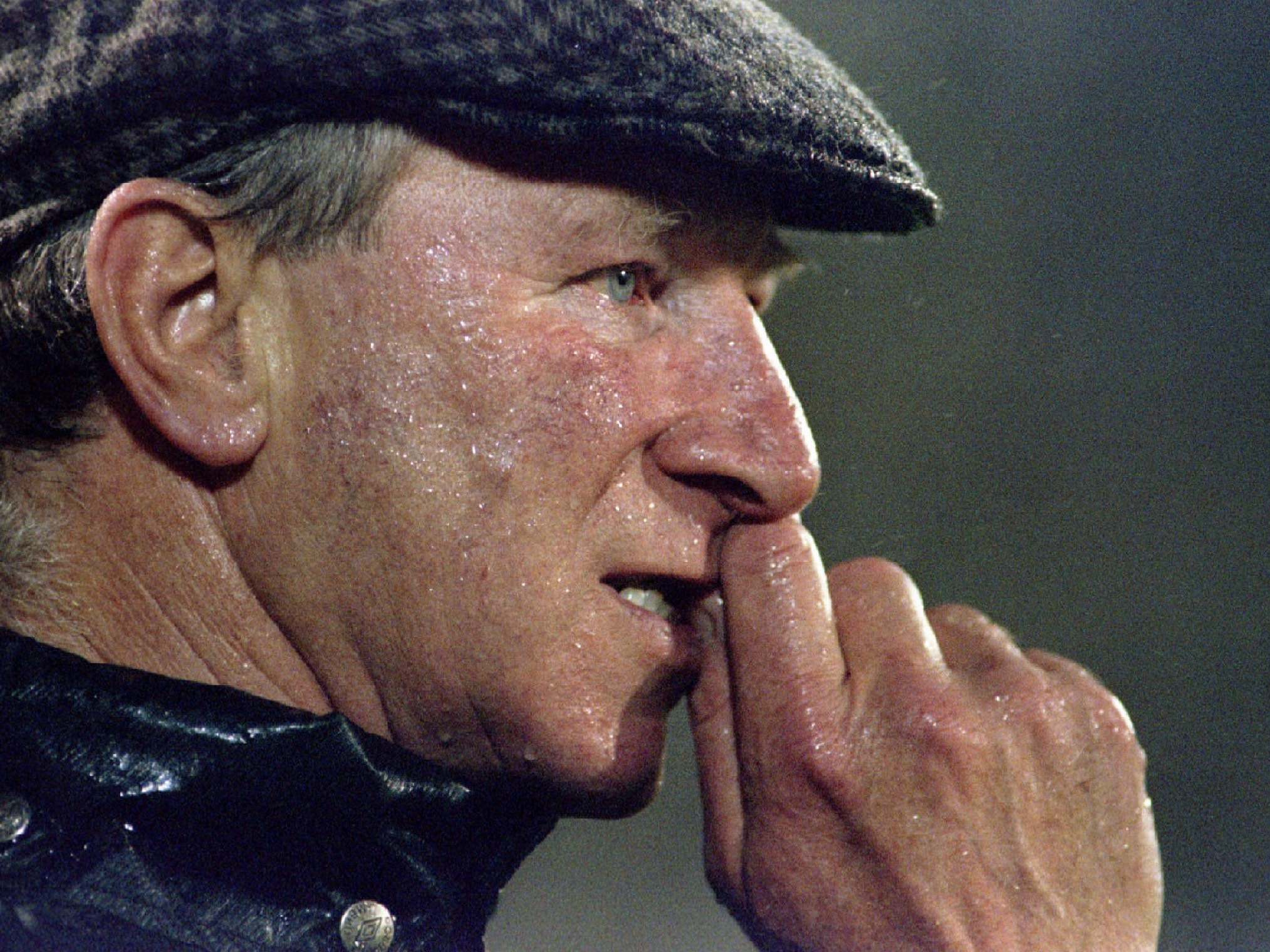

In June 2015, ahead of a friendly between Ireland and England at Lansdowne Road, the man that represents the greatest link between the two countries was brought out onto the pitch.

The whole crowd immediately started singing the only thing they could sing.

“Olé, olé, olé, olé…”

Those four words were the chorus of the Ireland team’s song for the 1990 World Cup, titled ‘Put ‘em under pressure’ - which were another four words always associated with ‘Big Jack’.

Within that refrain were a host of joyous memories and emotions, that all came flooding out in an instant. Charlton himself, so endearingly gruff through those glory years, let it out himself.

To any Irish person, that chant immediately brings you back to that glorious summer, and has become the soundtrack of every Irish sporting celebration since. You’ll even hear it at Eurovision.

Nothing, however, compares to Italia 90.

And nobody compares to Charlton.

An honorary Irishman, he was probably the country’s greatest ever sporting figure, and certainly its most influential. He was easily the most famous person in Ireland for a decade, and the most celebrated.

It’s difficult to overstate his impact, or even articulate it, without having experienced it or lived through it.

The Ireland that Charlton came to in 1986 was a very different country, and a very grim one.

The news was dominated by a dismal economy, mass unemployment, emigration, a heroin epidemic and the Troubles.

The conflict in Northern Ireland continued to completely condition Irish attitudes to the UK. Charlton’s first game, against Wales in February 1986, saw a banner that read ‘Go home Union Jack’.

He’d almost got the job by accident, due to a split in the vote, when Bob Paisley had been the favourite.

This kind of dysfunction summed up Irish football at the time, and a lot of Irish sport. There had been very little to celebrate, beyond a handful of Olympic medals, maybe the very occasional victory in the Five Nations.

Ireland had just never experienced any kind of success on a truly international stage. The football team had always had talent, but never enough, and never did enough.

Ireland had never qualified for a tournament, with their history characterised by catastrophic campaigns or agonising near misses.

Charlton was to change all that, and so much more.

He is even said to have had a tangibly positive effect on Anglo-Irish relations.

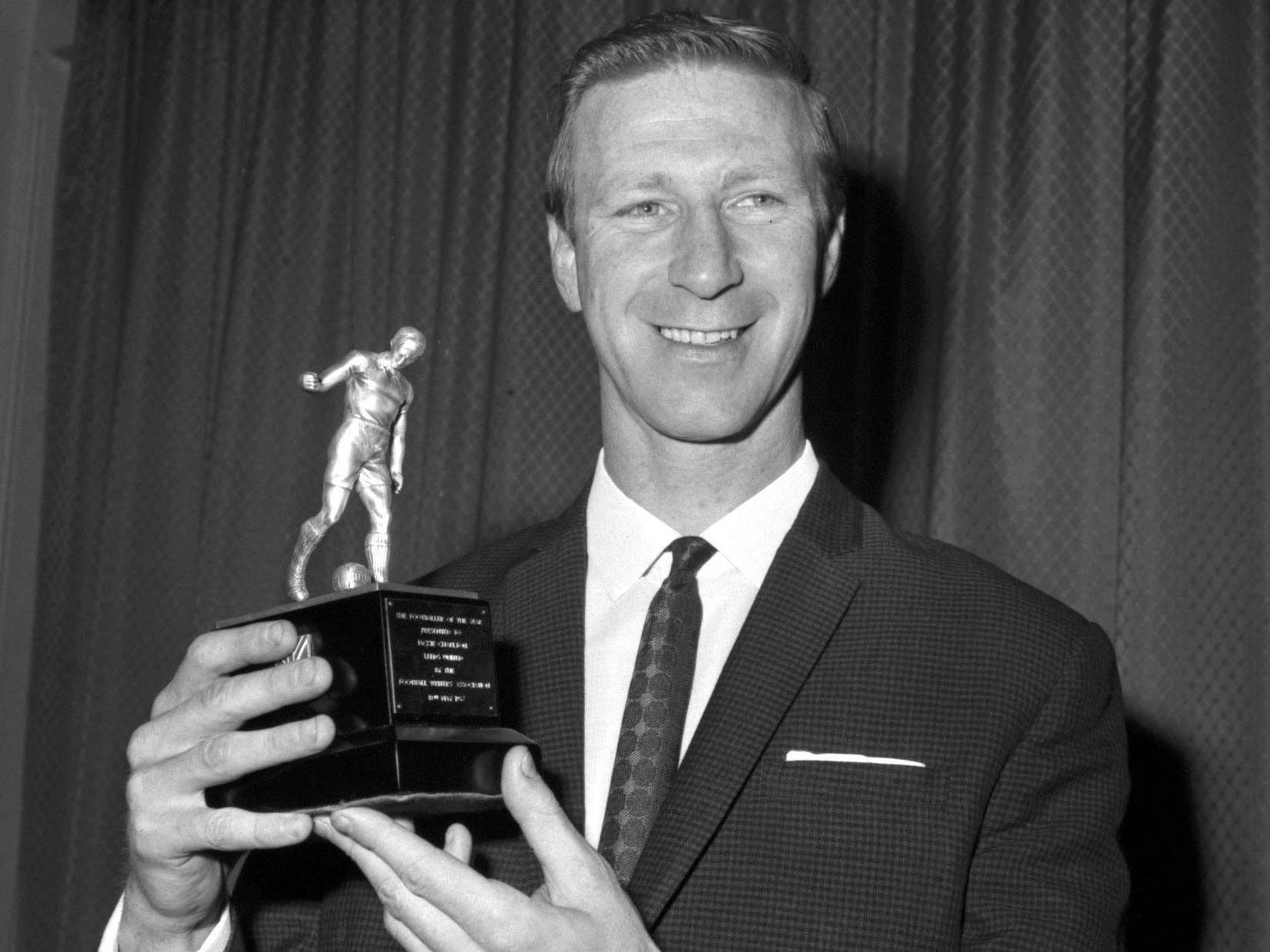

Twenty years after winning the game’s greatest tournament with England as a player, the new Irish manager travelled to Mexico for the 1986 World Cup, and declared he’d seen “nothing new”. That was a remarkable statement for a competition that saw Diego Maradona reach historic peaks, but Charlton wasn’t looking at the game that way.

He actually looked at the game in a completely different way to anyone, and in a manner that was truly visionary.

It was this that initially helped a limited player - by Charlton’s own admission - become a pillar of a centre-half for England’s World Cup-winning side and Don Revie’s great Leeds United team.

“I can’t play football but I can stop others from playing,” he said once, before unfavourably comparing himself to his brother, Bobby.

It was this that manifested itself in what almost seemed clairvoyance in his second life as a pundit. The best example was when he predicted how Nottingham Forest’s 1980 European Cup final against Hamburg would be won as the game played out.

It was this, however, that helped to change Irish history - and not just in a sporting sense.

In a piece of spatial perception that people would most associate with football figures like Pep Guardiola or Marcelo Bielsa, Charlton realised there were vast areas of the pitch behind international defences that were rarely used. The majority of play happened between both back lines.

“I’d seen the World Cup in Mexico, and it was like peas and a pod,” Charlton said on, of all places, Desert Island Discs. “Everybody played the same way through a playmaker in midfield, and unless the playmaker was in a good position to go at the back four, nobody would commit themselves forward.”

So, Ireland would commit themselves forward. Charlton’s team would attack those areas behind the defences with what now looks very modern pressing - “put em under pressure” - and then seek to maximise it by bombarding balls into the box from there.

This was the blueprint that can be seen in so many of the great moments, especially that first symbolic 1-0 win over England in Euro 88.

There were criticisms it was little more than long ball. There was also some dissent in Ireland - most memorably through former player Eamon Dunphy - that this was an unnecessarily crude use of what was a genuinely gifted generation of players like Liam Brady.

There was some merit in that argument, but a number of crucial counter-points.

First of all, that generation had been greatly boosted by Charlton’s intelligence in another way. He realised the advantage that Ireland’s citizenship laws allowed - whereby third-generation migrants could qualify for a passport - and scoured the UK for potential call-ups. John Aldridge and Ray Houghton were two of his greatest finds, who added an even greater emotional dimension to the team’s success, given the history of the diaspora.

Secondly, as basic as the football looked, it was from a truly sophisticated mindset. It was almost mathematical thinking.

“We had to design a game that would frustrate international teams at a level we wanted to compete at, and I had to come up with an idea,” said Charlton. “I give each individual player one individual thing to do.”

There were scenes of unbridled joy all over the country, people dancing in fountains, kids hanging out of cars with the flag, and the horns blaring. I was one of them

Finally, and most importantly, Charlton had to break this immense mental block that the international team - and maybe Irish sport - suffered from. You can take Liverpool’s complex about a 30-year wait for a title and multiply it several times. There were all sorts of Irish national neuroses and inferiority complexes wrapped up in previous failures.

Charlton smashed all that, and gave the country the most jubilant release.

There was naturally some luck to set it off, as these things tend to go. Ireland only qualified for Euro 88 thanks to an unexpected Gary Mackay goal for Scotland in Bulgaria.

That just fostered the feeling this was a blessed time, in so many senses.

The country was about to be taken on a magical, transformative journey, that it had never experienced before.

The 1-0 win over England at Euro 88 was a peak in its own right, rich in symbolism and history - “pandemonium” as goalscorer Houghton put it - but it was only the start.

Italia 90 was the true high point, maybe in Irish history. That is no exaggeration.

Anyone else watching on may be a bit puzzled about that.

From the outside, a small country that played reductive football failed to win any of their five matches, and only scored twice.

From the inside, it was just … pure joy. There’s no other way to put it. There was no other way to feel about it.

The Irish line most repeated about Italia 90 is from the late sports journalist Con Houlihan.

“I missed Italia 90. I was at it.”

That was because the country saw scenes of celebration it had never witnessed for anything else.

Streets were literally empty for games. The country came to a standstill.

That is emphasised by one story from the very height of Irish politics. During the last-16 penalty shoot-out against Romania - that has gone down as the greatest moment in Irish sporting history - prime minister Charles Haughey was giving a press briefing at the EU summit, since Ireland held the presidency.

He interrupted proceedings to tell journalists there was something on TV they should watch. Packie Bonner saved from Daniel Timofte, David O’Leary scored.

Ireland were into the quarter-finals of the World Cup. It was scarcely imaginable. Haughey danced. Grown men burst into tears. There were scenes of unbridled joy all over the country, people dancing in fountains, kids hanging out of cars with the flag, and the horns blaring. I was one of them.

It was all more reminiscent of liberation after war than sporting success. But then it wasn’t really about sport, either. It was the first time the country had done anything in a truly global sense. It was happiness that finally offset so many worries.

It may have gone even further than that. One economic theory has it that the new national confidence derived from Italia 90 was the driving force of the Celtic Tiger.

Whatever the truth of that, it’s certainly true that not even England’s victory in 1966 compares in terms of the impact on the whole country.

And it was all because of ‘Big Jack’.

When the team returned after being knocked out by hosts Italy, almost half a million people came out in Dublin for the homecoming.

Charlton’s last great victory came against the Italians four years later in New York. Another World Cup, another moment that meant the world to the country.

He gave the country something they’d never seen, something they’d never felt.

Those four little words, which will doubtless be played all over Ireland on the day of Charlton’s passing, brings it all back. It’s all because of one giant figure.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments