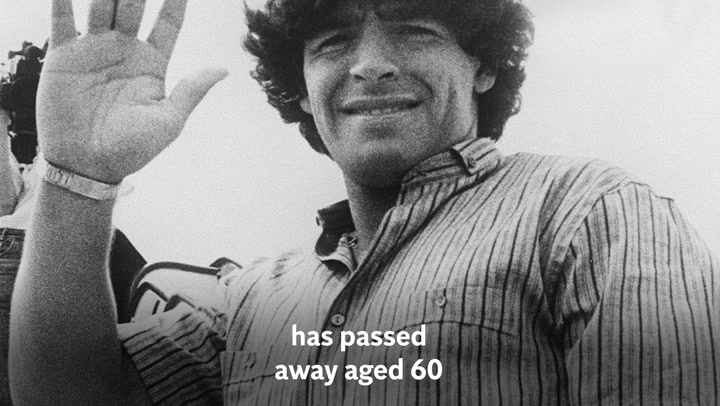

Diego Maradona, the two-faced god of football who never grew up

He was the best and the worst, predictably unpredictable and untrustworthy with anything but a ball. That is what made him the greatest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Old age was never an option for Diego Armando Maradona. He was the worst sort of child, someone who never grew up. The only place he felt a sense of responsibility was on the pitch. The only time he did not let anyone down was when he had a ball at his feet. Or his hand.

It is too easy to say he had a childlike quality. He was more like a regressed, indulged teenager who never quite realised where the boundaries were. Football is a haven against adulthood for us all, though; a place where players and fans can act like kids. Maradona was the essence of mischievous adolescence.

How good was he? No one was better. Playing was the only outlet for his maturity. He was so outrageously talented he could win a game on his own. But if he thought a three-yard pass to the left back was better for the team, he would play that ball. When he decided the only option was to beat an entire defence, he could do that too. With ease.

The infamous ‘Hand of God’ incident colours English opinions on the Argentinian genius. His two goals in the 1986 World Cup quarter final against England illustrated different sides of his personality: the cheat and the champion. It is sometimes forgotten how Bobby Robson’s team stormed back into the game in the last 15 minutes in the Azteca 34 years ago. Argentina were exhausted and on the back foot in the closing moments and Gary Lineker came very close to levelling the scores. It is a tempting notion that, had Lineker scored, England might have gone on to win not just the game but the tournament. John Barnes shut that theory down.

READ MORE: Pele leads football’s tributes for Diego Maradona

“If we’d have equalised, Maradona would have got the ball, gone up the pitch and scored,” Barnes said, dismissing the theory that England had any chance. “And if we’d have equalised again, he would have done it again.”

He was unstoppable in Mexico. And beyond.

The greatest feat of Maradona’s career was not winning the World Cup but leading Napoli to the Serie A title twice. Italian football was at its peak in the second half of the 1980s and early nineties but the Argentinian towered over the league. Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan are often spoken about as the greatest club side in history. They were brilliant, grown-up and cynical. They could not stop Maradona, even in the season they won their second consecutive European Cup.

Naples, a city of urchins, embraced him. He had that backstreet, threatening dynamic that Neapolitans embrace. Watch the brawl after the 1984 Copa Del Rey between Barcelona and Athletic Bilbao. Maradona, whose ankle had been snapped by Andoni Goikoetxea, the ‘Butcher of Bilbao,’ the previous year, drop-kicked an opposition coach in the head in a wild melee. His disregard for consequences defined not only his career but his life.

His team-mates at Napoli – and most of the port city – knew about his drug use and womanising but they chanted his name as heartily as did the ultras on the terraces of the San Paolo. Dressing rooms are places where jealously can run rife and egos abound but Napoli’s players were as in thrall to their talisman as the supporters. They were fans as much as colleagues. He turned fellow professionals into wide-eyed acolytes.

Much of his behaviour was infantile but that was part of his appeal. Childlike is often a synonym for innocence but there was nothing pure about Maradona. He was the embodiment of smirking shame; an imp that radiated danger, with a seductive power that drew people to him. He radiated magic. Sometimes it was of the black variety but it was always spellbinding.

He is gone too soon but it is awe inspiring that he lasted so long given his lifestyle and appetites. Maradona was as destructive to himself as he was to defences. He was the best and the worst, the two-faced god of the game, predictably unpredictable and untrustworthy with anything but a ball. That is what made him the greatest. It is hard to decide whether to be sad or happy that he died before he had the chance to grow up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments