Alun's story: a new Hillsborough film reveals the unremitting memories of the survivors

Tuesday night's S4C documentary revealed new, extraordinary testimonies

The sorrows of Hillsborough reside in the small details. The conclusion of last year’s inquests brought to light, for example, how those who died were referred to by a number in correspondence that their families subsequently received. Arthur Horrocks was ‘No 92’, though to his family he was the father and husband who taken on a job which, in some ways, he’d not been so comfortable with – selling insurance policies for ‘the Pru’ – just to make a better life for them all. Even 27 years on, when the inquest verdicts came, the wife Mr Horrocks left behind did not feel comfortable speaking publicly about her loss. So deep are the scars.

On the face of it, another documentary committed to describing the lasting psychological toll seemed unlikely to shine new light through these windows. Tuesday night’s S4C film Yr Hunllef Hir (‘The Long Nightmare’) had been a reminder of the more subtle struggles of some survivors – for example, feeling that their kind of grief is a self-indulgence when others have lost so much more. And then one searing and quite extraordinary piece of new testimony emerged.

The film focussed on those from North Wales who travelled to the Sheffield Wednesday ground – the affinity and links between that part of the world and the sea port 50 miles away always having been strong – and it was supporter Alun Wyn Pritchard whose story broke new ground. Quietly and steadfastly, he described how it was to have been one of those who, by an indefinable process of fate or chance, managed to land on the right side of the line between those lived and died that day in 1989.

The supporter standing beside him had asked him to make some space so he could pass his child up out of the Leppings Lane terrace to those in the tier above and though that process briefly seemed to have succeeded, the boy did not make it out, for reasons which were never clear. (“He came back, crying. I still don’t know what happened to that little boy.”) That was just before Mr Pritchard began to suffer the unimaginably terrifying consequence of being among “too many people, squeezing the life out of one another,” as the programme’s main witness, Dylan Llewelyn, described it.

The man beside Mr Pritchard began to suffer nose bleeds and other clinical consequences of the crush, related in the film, which proved fatal, and then he began to experience the same. Mr Pritchard’s recollections of the fateful minutes which followed are flashes, as were those of Mr Horrocks’ family, who also just about made it out alive. The sound of swearing. The bleeding. An inability to raise so much as a finger, amid the sardine tin compression. The awareness of being lifted onto one of the advertising hoardings which were commandeered, there being so pitifully few stretchers available. Seeing, at some stage in the mayhem – perhaps when being led towards the hoarding, what it advertised, ‘Heals of Sheffield.'

The programme’s other disclosures are equally matter-of-fact and the more powerful for it. The brother-in-law of Andrew Sefton, who died, had already been asked to examine two bodies before the zip of a third bag was pulled back to reveal his son. The mother of Andrew Sefton was on the floor of the place where that process had taken place, inconsolable, when two police officers walked around her. But it is Mr Pritchard, a North Walian clearly disinclined to show of emotions, whose words go to the core of it all. “I was going in and out of consciousness. I thought it was a dream,” he said. “It’s something I’m trying to forget. It’s difficult. Yes. It doesn’t matter. It always comes back.”

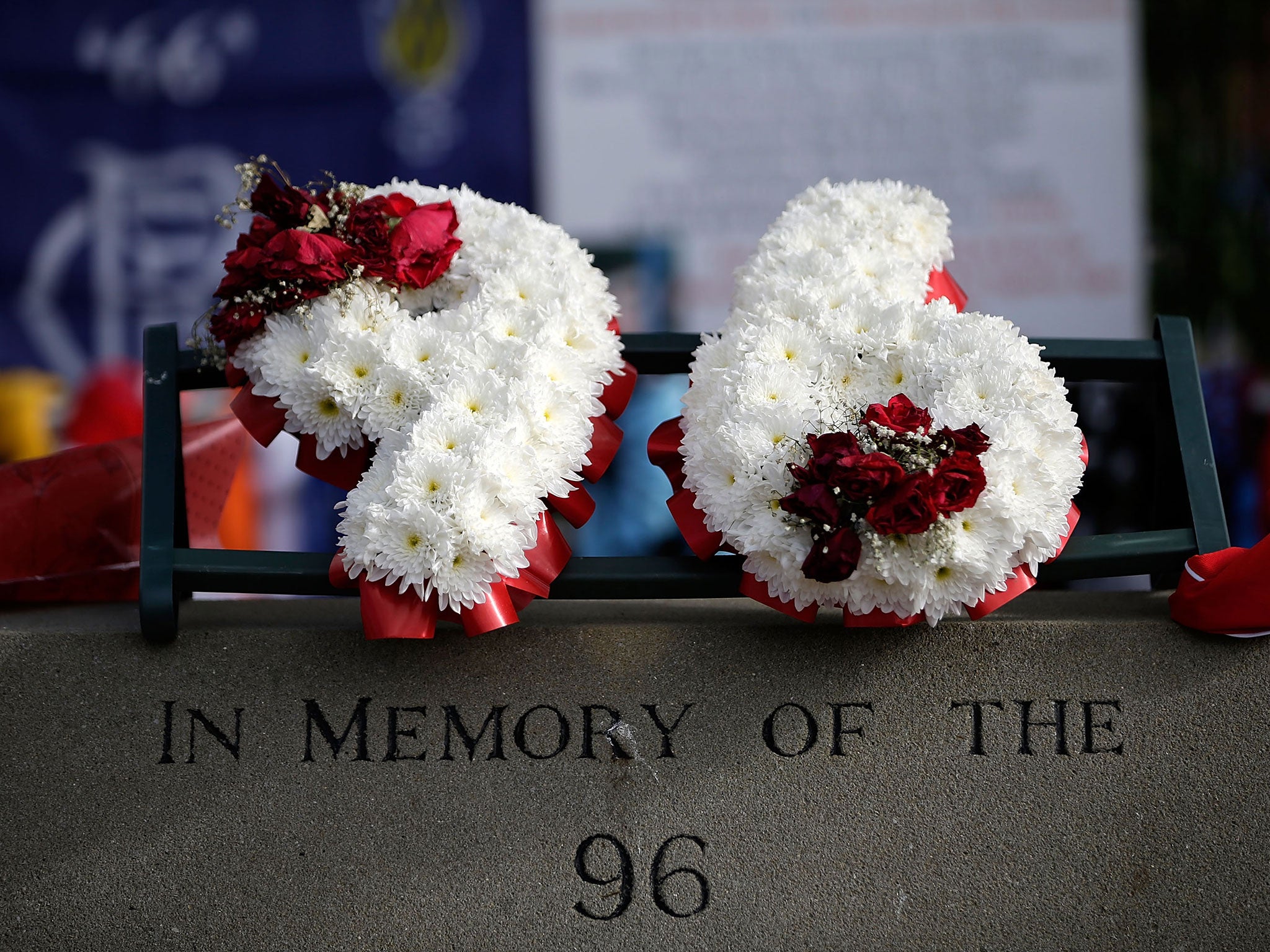

Though 96 died, just as many - or more - very nearly did and have lived with that realisation. As Professor Phil Scraton, principal Hillsborough investigator, reveals, we will never know quite what a toll that bright Spring day in 1989 really took.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks