Euro 2016: Lars Lagerback's Iceland have cometh and they could be here to stay

The team of the tournament so far can attribute their succes to an old school coach who believes in doing the hard yards

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The three policeman were jovial, but firm. One indicated his gun with a grin and said, ‘you could go in, but you would have to get past this’. We were stood outside Iceland’s new field of fantasies, the Complex Sportif D’Albigny, a cluster of training pitches in this picture-postcard town in the foothills of the Alps. But we were not going to get in.

Behind the ‘ring of steel’, as these security operations are traditionally called, the breakout team of the Euro 2016 were beginning their preparations to unseat another of the game’s giants. England may now have reached a half-century of hurt but they remain, in Icelandic eyes at least, as much giants as the Dutch team despatched in qualifying, and the Portuguese irked in the group stages.

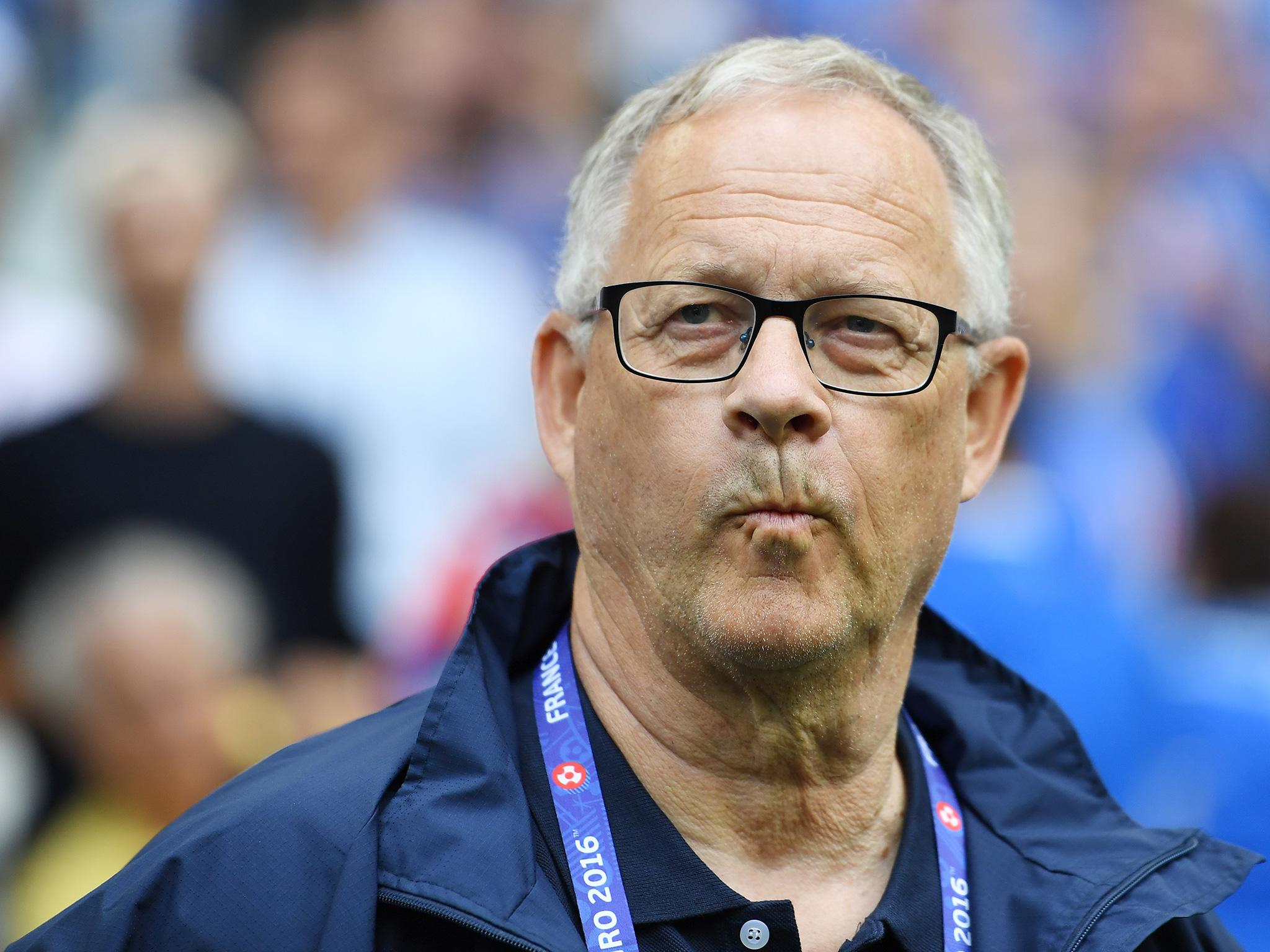

Thus, as the mercury headed past 30C, and 250 yards away sunbathers relaxed and swam in Lake Annecy, players nurtured in far cooler climes readily sweated under Lars Lagerback’s demanding gaze. The Swedish coach, a veteran of five major tournaments with his native country and one with Nigeria, has incorporated some of the new methods of player psychology and sports science, but at heart remains an old school believer in doing the hard yards on the training pitch drilling his players. In that respect he is much like the man he hopes to defeat in Nice on Monday, Roy Hodgson. This is hardly surprising as Lagerback is a Hodgson disciple.

When they began working in Sweden in the 1970s, Hodgson and his erstwhile coaching partner Bob Houghton influenced a generation of Scandinavian coaches, including Lagerback. “They inspired me with their methods,” he says to the international media, who have come to a town centre hotel to find out how Iceland are doing it. In his perfect English, Lagerback adds: “We didn’t work organising a team in such a concrete way as they did in training. It was logical. You would have been stupid if you didn’t adapt to that kind of way of working.”

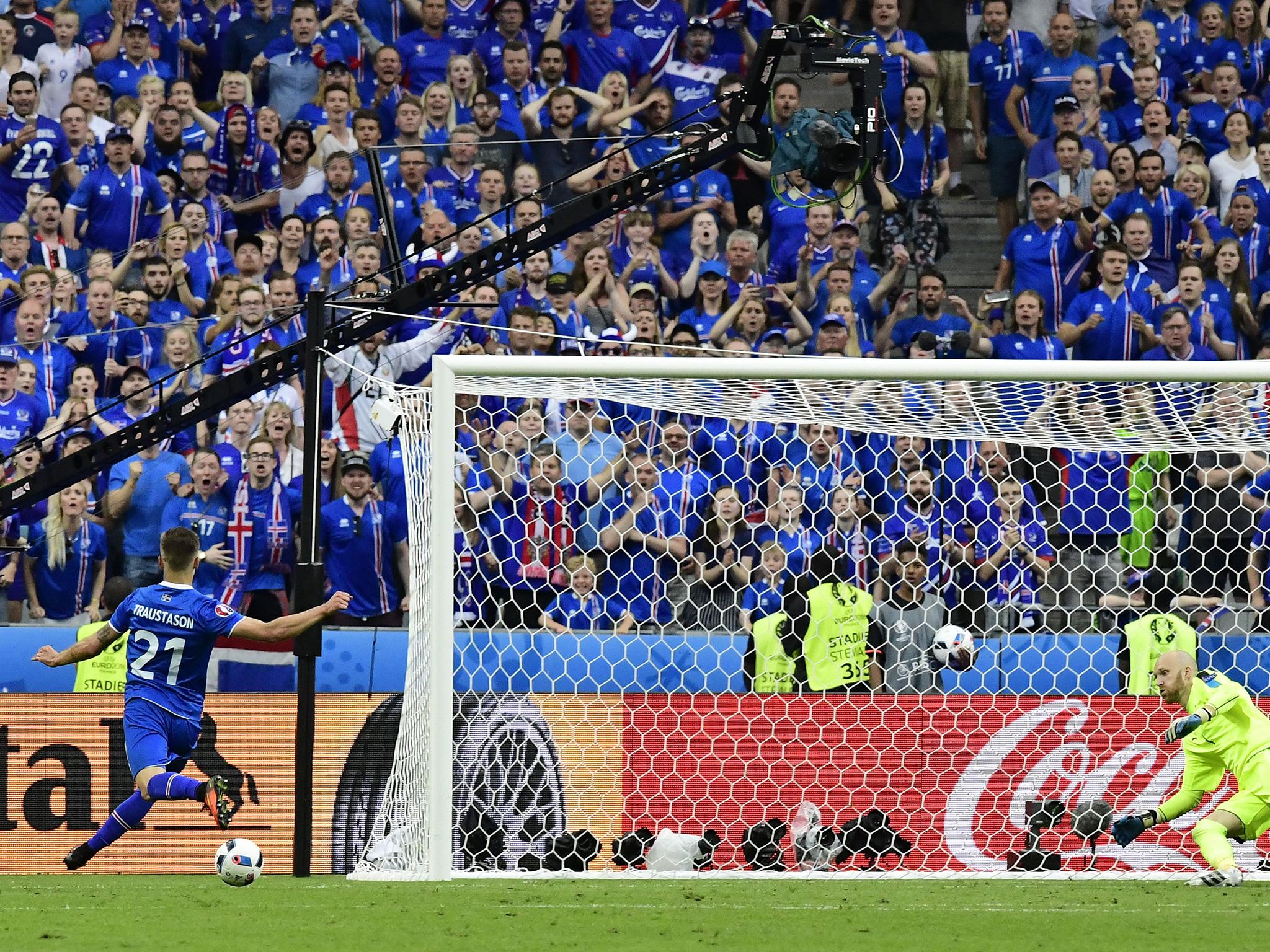

Beside him sit Arnor Traustason and Eimar Bjarnason, the taker and maker of the last-minute goal that beat Austria to seal Monday’s meeting with England. They played respectively for Norrkoping and AGF Aarhus last season and have never experienced anything like this, but seem unflustered.

Lagerback has adopted the use of motivational phrases and images beloved of the new breed of coach. In their meeting room, says Bjarnason, “is a picture of a chihuahua chasing the rhino - not that we are the chihuahua!” he laughs. There are also quotes from the likes of Einstein, but all this is back-up to the tactical work.

“We try to find good quotes from people to underline the mental approach,” says Lagerback. “They always get something from it, though I don’t know how much. From a leadership point of view, the most important thing is on the pitch. A well-organised team should know what they are doing on the pitch.”

Like Hodgson, Lagerback also has the self-confidence and experience to allow input from leading players. “We had a team meeting,” he says, “and Eidur Gudjohnsen stepped in to say a few words about not being satisfied. He challenged them to take the next steps now. We are not satisfied with the way we have performed, especially in the attacking part. Of course what we do in the training pitch is most important now, because we are not satisfied.”

What Lagerback has brought to Iceland is professionalism and higher expectations. This has led to improved results and, consequently, self-belief. It is the same with Hungary under German coach Bernd Storck, and Albania under Italian Gianni Di Biasi. The coach of another minnow, Northern Ireland’s Michael O’Neill, has less experience, but is equally meticulous, adapting his team game-by-game depending on the opponent.

This is one reason these less fashionable teams have impressed at Euro 2016. Another, says Lagerback, ironically given the day’s seismic events, is the globalisation of European leagues that followed the Bosman ruling, made by the EU’s European Court of Justice.

“You’ve seen this development since 1992 when the Bosman ruling came in,” he says, “and it’s accelerated in last five or six years. All countries have players in good leagues and good clubs. That’s why it’s getting tighter and tighter. Also, I think smaller countries are getting better in developing football, with better facilities and more professionals on the playing and coaching side.”

Iceland are an exceptionally good example of this. At the turn of the century, inspired by Norway’s progress on the back of constructing indoor facilities, the football federation began an investment that puts countries like England and Scotland to shame. There are now 30 full-size all-weather pitches in this country of 320,000 people, including seven indoors, and nearly almost 150 smaller artificial arenas - enough to ensure every school has access to one.

Investment was not just in buildings. Everyone who coaches must be qualified to Uefa B level - a standard that requires two weeks training followed by months of logged coaching sessions then assessment. That’s everyone, including the level at which British kids are being ‘coached’ by a parent with little technical knowledge and, all too often, a fixation with the result rather than the performance.

Norway’s bubble has long since burst but Iceland hope their focus on coaching will ensure the current tournament will not be a one-off adventure, but the start of regular participation. “It’s hard to speculate on the future,” says Lagerback, who will step down after this tournament, “but the U21s, they have beaten France in Euro qualification, the U17s are doing well. As a small country, like Iceland or Sweden, it’s always difficult to qualify. You don’t have the number of players to choose from as other countries, but the situation is positive.”

Iceland are staying at a lakeside spa resort on the other side of Annecy. Security is tight there too. "We are used to more freedom and less security,” defender Kári Árnason has said, a view echoed by Alfred Finnbogason who added: "We Icelanders are not used to this". They may have to get used to the presence of armed policeman, and Europe to their presence at the top table. The Icemen have cometh, and they are here to stay.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments