Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

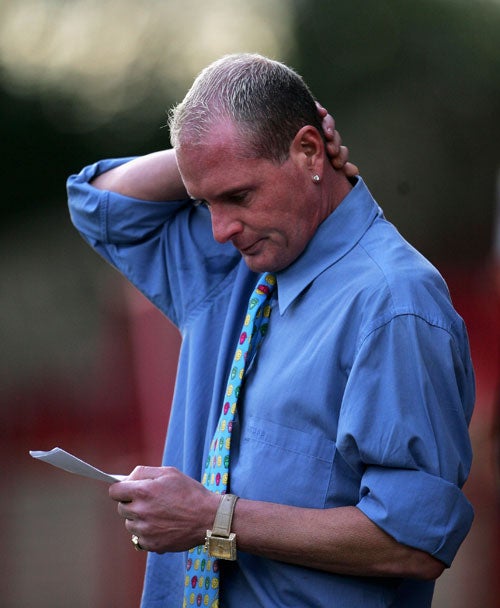

Your support makes all the difference.If you want to know what it was like having Paul Gascoigne as manager of Kettering, imagine Oliver Reed appearing at the local amateur dramatic society or John Daly installing himself as the pro at the municipal golf course. The personality was huge, the stage tiny; the ending predictable and messy.

Leeds, who visit Rockingham Road in the second round of the FA Cup today, had the 44 days of Brian Clough. Kettering had the 39 days of Gazza, intimately portrayed in a book of the same name by Steve Pitts, who was sports editor of the Kettering Evening Telegraph on the day in October 2005 when Gascoigne, having just injured himself in rehearsals for Strictly Ice Dancing, arrived for his first job in football management.

His brief, laid out by the new chairman, Imraan Ladak, was to put bums on seats and transform Kettering into a League One side. The first was fleetingly achieved; the second was a non-starter, although major strides have been made since the spotlight was turned off.

As ever, Gazza was likeable. He bought pizza for the players after training – "because that's what they do in Serie A"; he turned on the town's Christmas lights; he signed every scrap of paper put in front of him; he insisted on a jacket and tie in the boardroom. One middle-class caller phoned the club to ask if Gascoigne would like to join his dinner party. However, he appears to have barely understood the level of football he had descended to.

"It wasn't even the Conference, it was the Conference North," said Pitts. "It is a world of long balls, hard work and crap pitches. And Gazza shows the team a video of France winning the 1998 World Cup and tells them this is how they are going to play. He hadn't got a clue about football at this level.

"Kettering had a close-knit dressing room that enjoyed the prospect of Gascoigne becoming their manager more than they enjoyed being managed by him. They were a team of factory workers and warehousemen, whose jobs were more important than their football. When he said he wanted them to go full-time it scared them – let alone the fantasy talk of Les Ferdinand or Steve McManaman coming. They wondered where they fitted in to all this."

Even the publicity was problematic. By then, Gascoigne loathed the press to the extent of devoting one of his first team talks to advising his players how to cope if they were followed into a nightclub or pictured with a woman, although as the player Christian Moore pointed out: "I am married, but if I were out with a girl, do you really think it would be front-page material?" Not even in the Kettering Evening Telegraph.

"The trouble was, Gascoigne craved publicity," said Pitts. "There were 70 journalists for his first press conference and a dozen for the next. Then I [was] the only reporter and he kept me waiting two-and-a-half hours. They resorted to bussing in students from a journalism college. The lack of interest hurt. He quickly became just another manager in the Conference North, then a manager in the Conference North who was not doing well and finally a manager in the Conference North who was falling apart."

The problem was not so much results, which were average (Kettering won three of eight games under Gascoigne), but the booze. Kettering's former chairman, Peter Mallinger, said: "Apart from a pub, a football club is the worst place for an alcoholic – it is full of drink."

Mallinger's first encounter with Gascoigne saw him swig from a bottle of Harvey's Bristol Cream that had been gathering dust in the manager's drinks cabinet since the Christmas raffle. Kettering trained only on Tuesdays and Thursdays and there was an ocean of time to fill. White wine replaced sherry, brandy replaced wine and, with the death of his fellow alcoholic, icon and friend George Best, Gascoigne collapsed completely.

The Damned United ends with Clough driving away from Elland Road in his Mercedes shouting: "I've come up on the bloody Pools." The £25,000 severance payment he received in 1974 set him up for life. Gascoigne does not appear to have asked for anything and spent the night after his sacking soused in alcohol in a police cell in Liverpool. For Clough, European Cups and League championships beckoned; for Gascoigne there were only requests to appear on I'm A Celebrity... Get Me Out Of Here!

'Thirty-Nine Days of Gazza' by Steve Pitts is published by Pennant Books. Kettering v Leeds is on ITV1 today, 1.30pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments