The crying Caesar: Paul Gascoigne's Roman days

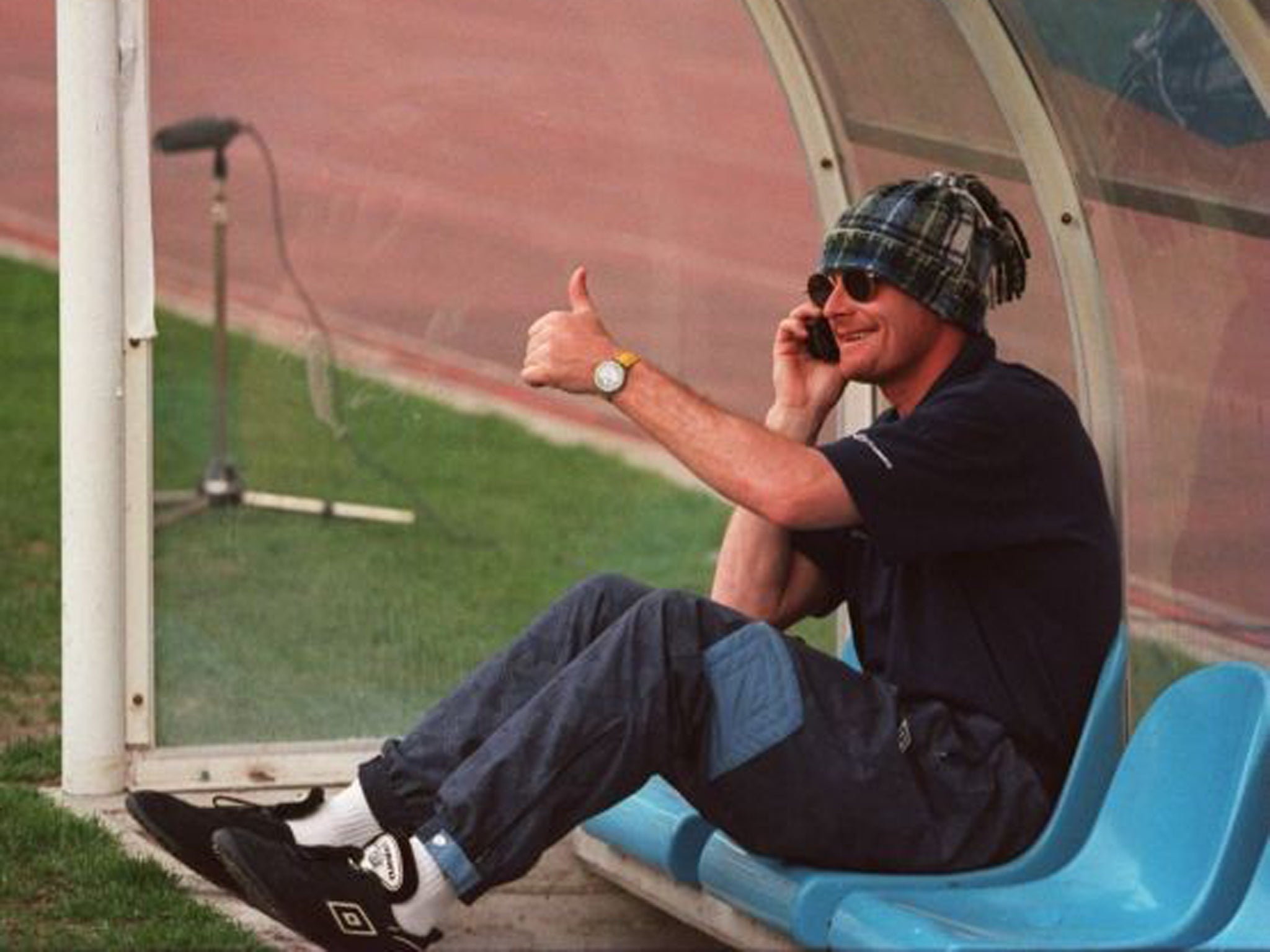

On Thursday the England legend returns to Lazio, where he briefly shone in the 1990s. His former assistant tells Tim Rich of the adulation, loneliness – and some disastrous Italian lessons

For the first time in 15 years, Paul Gascoigne will set foot in what was once his own coliseum, Rome’s Olympic Stadium.

There were not thousands at Fiumicino Airport to greet him as there were when he made his first journey to join Lazio when a high court judge asked if he was more famous than the Duke of Wellington after Waterloo.

The Olympic Stadium will not be full for the Europa League fixture with Tottenham as it was jammed when he scored in the Rome derby in 1992. However, he might just break down in tears as he did then, running arms outstretched towards the Curva Nord, where the flares had turned the air blood red.

Gascoigne’s time at Lazio was stained by too many tears and very few of them were of joy. “Looking back, I don’t think too many people had Gazza’s best interests at heart. We let him down. Everyone did, from the president downwards,” said Jane Nottage, who was Gascoigne’s personal assistant and commercial manager.

“People could have stopped the downward spiral but they didn’t. Lazio wanted to keep him playing and, if they had sent him for psychoanalysis, they could have lost him as a player for months.

“He wouldn’t have been able to do the commercials and so it wasn’t in anybody’s best interests to help him. The only people who did have his best interests at heart were his parents and they couldn’t cope with everything else that was going on in Rome.”

When John and Carol Gascoigne did come to what the media called the “Villa Gazza”, they tried to help by creating an allotment, although Nottage had to explain to the owners why their manicured gardens now contained carrots and peas.

What astonished Nottage was how little research clubs did into the men they signed. Racehorses would have had their personalities more deeply examined. “I did some work with Ian Rush at Juventus,” she said. “He grew up sharing a bedroom with his brothers and, when they stuck him in a villa on his own, he couldn’t cope. The only time he did well was when two of his best mates had come over and I’d put them in a hotel. His mates had the twin beds and Ian slept on the floor.

“If you think about Gazza, he had been dumped out in this villa with a girlfriend [Sheryl] whom he had met relatively recently and didn’t, I think, really know and he suddenly had two step-children to deal with.”

There were not many people he could talk to. “He had Italian lessons but they didn’t produce the results the club wanted. There was one incident when the Lazio president, Sergio Cragnotti, arrived at the training ground, surrounded by his hangers-on and Gazza went over and said, in Italian: “Your daughter has big tits”.

To Nottage it was an example of Gascoigne’s unaffected character, less calculated than David Beckham’s, less guarded than Wayne Rooney’s. He had no interest in being a brand, although he had a surprisingly good head for figures: “he could tell his income in a heartbeat.” To Lazio’s coach, Dino Zoff, the conversation with his president was another example of a fatal lack of discipline.

Nottage found Zoff icy and remote: “not the sort of person you could go to with a problem”. The contrast with the managers Gascoigne was used to, Bobby Robson and Terry Venables, was acute.

Only with the fans, in Rome and beyond, who recognised in Gascoigne the street footballer in themselves, was he a success. With ordinary people he had, in Nottage’s eyes, a “Princess Diana” quality.

Attendances at Lazio were up 5,000 a game, coverage of Serie A on Channel Four drew in four times as many viewers as the first season of Premier League football on Sky.

Not much of this benefited Gascoigne, who in two seasons flitted sometimes brilliantly sometimes fitfully through 39 games for Lazio. His reported salary of £10,000 a week was dwarfed by what Ruud Gullit earned at Milan.

When he left for Rangers, the newspaper La Repubblica commented: “What does it matter if he has not earned millions in endorsements? In Italy, Gazza was supposed to have been a front-cover personality and a money-making machine. He has been neither but he has excited everyone with his impishness and his tears.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks