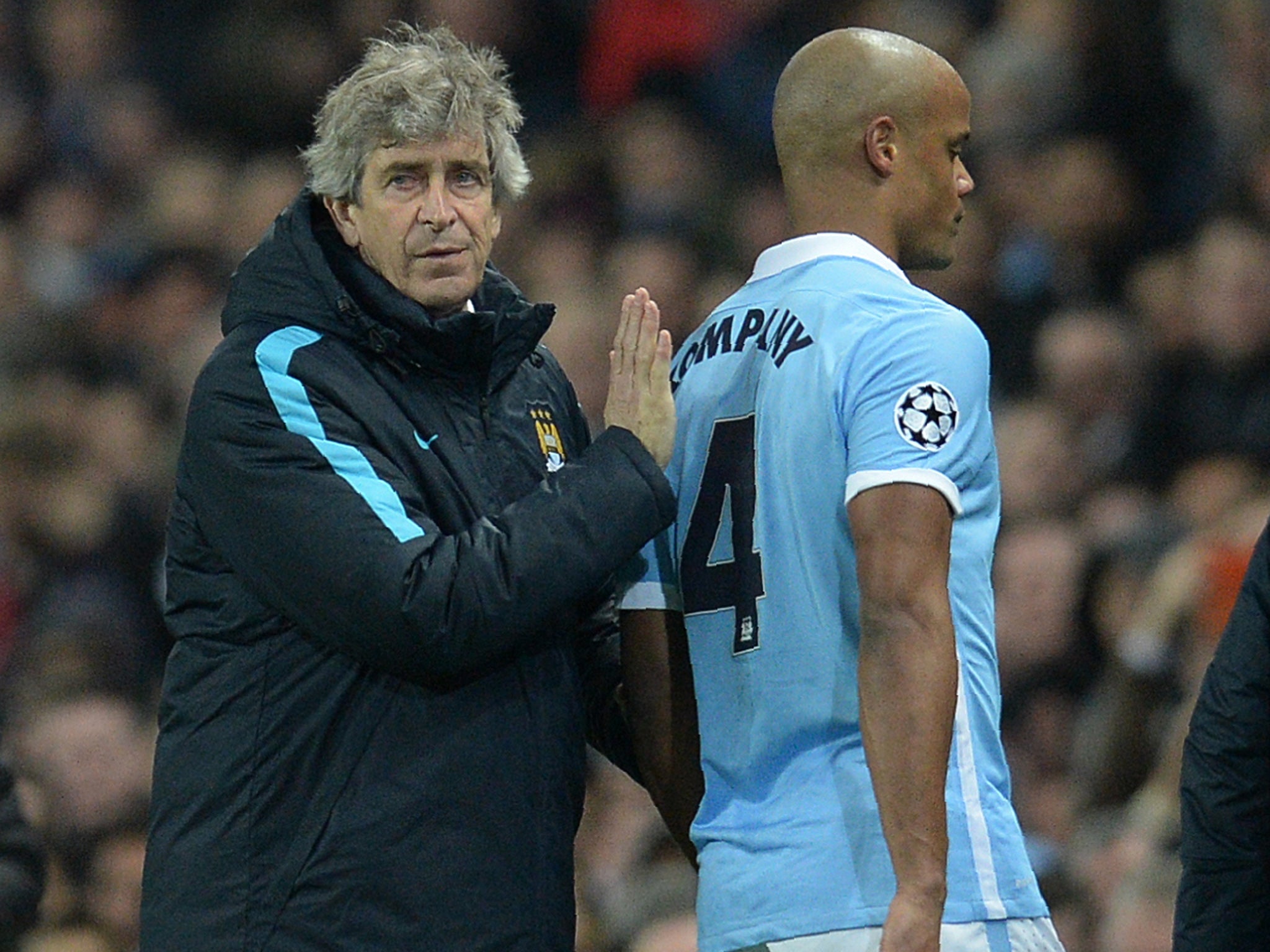

Manchester City 0 Dynamo Kiev 0 comment: Vincent Kompany's calf puts onus on Eliaquim Mangala's form

Kompany pulled up with another injury, this time his calf, after just five minutes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For Achilles, it was his heel. For Vincent Kompany it was his calf. When the Manchester City captain pulled up a few minutes into a game whose result was already foretold, it was the 14th time he had suffered a calf injury since becoming one of the club’s finest signings eight years ago.

The look on Kompany’s face as he walked away, tearing off his armband and handing it to Sergio Aguero, was the fury and frustration of an athlete constantly betrayed by his own body. Kompany is nearing 30, an age when persistent complaints start to matter.

On Boxing Day, against Sunderland, Kompany had returned as a substitute after a six-week absence in which Manchester City had not managed a single clean sheet, lasted five minutes and then came off almost in tears.

This time, he had attempted to turn Oleh Gusev and immediately felt something was wrong. Kompany pushed the ball out of play, sat on the pitch and informed the referee he needed to leave.

Before the game Kompany had given an interview in which he discussed his comeback. When he talked of his return it was in terms of a man looking back on the bad times from a position of strength. “My whole life at the moments is about forgetting what has gone before,” he said. Now what had gone before came back, cruelly and spitefully, to torment him.

Perhaps it would have been better had Manuel Pellegrini been allowed to ease his captain back in but, as Kompany himself acknowledged, February and March are not the months when footballers can be given gentle reintroductions to the game.

A little over a quarter of an hour later, Kompany was joined in the home dressing room by Nicolas Otamendi. The Argentine had collided with Vitaliy Buyalskiy, and then punched the air with frustration after he had launched the ball forward. Otamendi limped to the sidelines, fell flat on his back and crossed himself as Martin Demichelis replaced him.

The loss of Kompany will be the one that causes the most anguish in the blue half of Manchester but if Otamendi is out for any length of time, it will hurt City’s attempts to go beyond the quarter-finals of the European Cup. The sight of Eliaquim Mangala taking a swipe at thin cold air as he attempted to clear one of Dynamo Kiev’s rare attacks will not fill Europe with fear.

If Manchester City are to fail to win back the Premier League title, it will be because they have managed to beat only one team, Southampton, in the current top eight. Their best performances have been reserved for away games in the Champions League.

The 3-1 wins in Seville and Kiev each featured Otamendi and Kompany at their best. Here was evidence of a central defensive partnership that would survive the transition from Pellegrini to Pep Guardiola, who would most certainly not be enthused about the prospect of anchoring his defence around Mangala.

At £42m – five times what Mark Hughes paid for Kompany – Mangala threatens to match Malcolm Allison’s £1.4m cheque for Steve Daley, which has been described as “the biggest waste of money in football history”.

With the game an hour old, Mangala was turned by Andriy Yarmolenko, who produced Dynamo Kiev’s first and almost only worthwhile opportunity of the night, which turned out to be a shot straight at Joe Hart.

Kiev, who had never won any sort of game in England, let alone by three clear goals, knew they had wrecked their chances in their own stadium.

There have been only five teams in the history of the European Cup who have progressed after losing the first leg at home and only one, Ajax in 1969, have done it after losing 3-1 at home. Ajax had Johan Cruyff to unleash against Benfica and even Cruyff in his pomp would have struggled to raise this game from the dead.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments