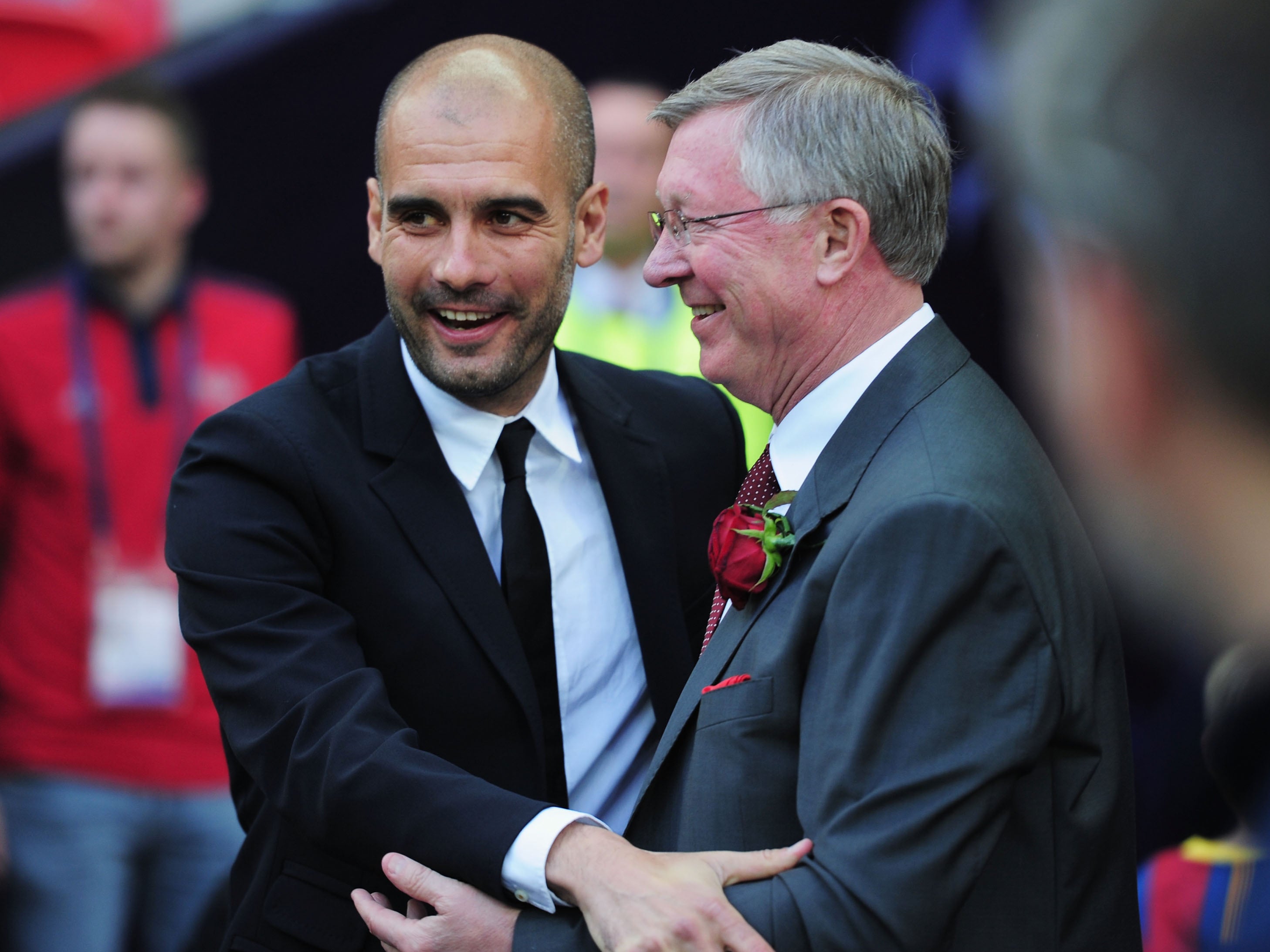

Barcelona vs Manchester United 2011: 10 years on from Pep Guardiola’s masterpiece

The win at Wembley remains Guardiola’s legacy performance, his greatest achievement and a standard he is still trying to reach a decade on, writes Miguel Delaney

Around the 80th minute of a performance for the ages, Wayne Rooney finally got close enough to Xavi Hernandez to just say something. “That’s enough,” the Manchester United forward pleaded with Xavi. “We’re dead. You can stop playing the ball around now. You’ve won.”

Barcelona did much more than win that 2011 Champions League final at Wembley against Manchester United. They offered a grand display of football perfection, as a whole team rose to their highest level. That was a level in turn lifted by Pep Guardiola, as he oversaw the culmination of his unique idea of the game.

It remains his legacy performance, his greatest achievement, and a standard he is still trying to reach a decade on. Whether he can quite do that is open to question, even as so many believe his own idea has evolved.

That victory did more than mark an era for Barcelona. It was a performance people will forever point to, as a perfect articulation of the football that was dominating and redefining the sport at the time. Wembley 2011 was one of those exquisitely rare occasions when one of the showpiece fixtures like the Champions League final offers a statement, as well as a state-of-the-game address. Barcelona’s victory was the equivalent of Real Madrid 1960, Ajax 1972 and AC Milan 1989. The defeated Sir Alex Ferguson even acknowledged this in his second autobiography, describing Guardiola’s side as “the team of their generation”.

Pedro, who scored the opening goal in that 2011 final, told The Independent it was the performance of a generation - and beyond. “It was historic. For me, it’s the best ever, and for everything - the best team, the best player in the world, and a philosophy and idea of play that was so clear.”

That was what was so special about it. Everything came together. Michael Carrick described it as “the most complete performance” he’d ever seen.

As is always the case in football, and particularly in a competition as prestigious as the Champions League, it was actually previous failures that enriched and completed the occasion.

Guardiola’s side had won a first Spanish treble in 2008-09, but there was a deep sense of regret they hadn’t become the first club to retain the modern Champions League the following season. It was felt that they needed another signature achievement to really fulfil the greatness of this generation. Guardiola even feared that so much success might have sapped the necessary intensity of his side, especially since a core of the team were just as dominant with the Spanish national team. “We had no idea how the team would be after having won so much, including the World Cup,” he later said. Earlier that season, Gerard Pique spoke of the weight of expectation that hung over the team.

“We’ve had a couple of good seasons. But what you can’t forget is that in the history of the game there have been some unbelievable teams, so we still have a way to go before reaching those levels. When the years have passed, we can calculate what we’ve achieved and draw comparisons.”

On the other side, that 2008-09 season also weighed on Ferguson. The Champions League final defeat of United in Rome was confirmation of this Barca team’s ascension, but the great Scot felt his side had let themselves down. Ferguson firmly believed for two years that the main difference between the teams in May 2009 had been an “off night” for United. He believed they didn’t do themselves justice.

This sense of legacy governed much of his thinking. United had eliminated Frank Rijkaard’s Barcelona in the semi-finals of Ferguson’s second Champions League victory, in 2007-08, but it was through a counter-attacking approach devised by Carlos Quieroz that the manager “hated”. If he was going to win that third European Cup - which at that point would have made him the only manager to match Bob Paisley - he wanted to do it in a manner befitting the feat. There was even a feeling that he might retire if he finally got that record. If so, it was little wonder he was concerned with going out in the right way. “We are not going to the Champions League final to sit back,” he told his players on the night.

“I had reached the stage with Manchester United where it was no good us trying to win that way,” Ferguson later wrote. “I used those tactics to beat Barcelona in the 2008 semi-final: defended really deep; put myself through torture, put the fans through hell. I wanted a more positive outlook against them.”

He wanted, in short, to offer the performance Barcelona ultimately did. That approach probably helped Guardiola’s side to do exactly that. Many senior United players had serious reservations. Football was that point at a stage of tactical development where the game was still adapting to the revolution caused by Guardiola. In the absence of modern pressing systems, the only approach that had even proved occasionally successful against Barcelona and Spain was to sit as deep as possible, cede the ball, and hope it bounced your way.

“We won the tie in 2008 by sitting back and frustrating over two legs,” Rooney told Jamie Carragher for his excellent account of the 2011 final in ‘The Greatest Games'. “In my opinion that was the only way you could beat them. You needed a bit of luck as well, but it worked. I think it made a difference that the assistant, Carlos Queiroz, was still there then. Carlos was brilliant with Fergie. Whenever the manager was following his instincts and thinking “we’re going to attack”, Carlos would make him rethink.”

No one as influential as Queiroz was trying to persuade Ferguson of the value of a more pragmatic approach this time, although an element of doubt was perhaps revealed by the manager asking his senior players whether they were happy with the tactics. Ferguson was insistent on doing what no one else did and pressing Barcelona high, to bring out United’s attackers. Both Ferdinand and Nemanja Vidic discussed the issue among themselves before expressing their concerns to Ferguson. The centre-halves stressed that it was going to be too difficult against this team, that this is why no one does it. “It’s different for them.” Ferguson said it would be different for United, and that the same 4-2-3-1 as in 2009 could work this time.

All of this articulated the central tension in facing this Barcelona, and why they presented one of the greatest challenges in football. Their movement and rotation was at such a level of sophistication that there was always another gap to cover. Attempting to find the balance between protection, not just inviting more pressure, and offering some kind of threat was at times close to impossible.

This was one of those times.

A particular problem for the game, and Ferguson in this fixture, was that Barcelona had evolved significantly in the two years since 2009. The core players now naturally understood Guardiola’s system - which was based on learning a map of the pitch, and memorising where to move in relation to that and the ball in any given moment - to the point that it was internalised. The players brought in from outside were meanwhile particularly suited to the play. While Thierry Henry and Samuel Eto’o may have been collectively superior to Pedro and David Villa as centre-forwards, that was the issue. They were centre-forwards, whereas Pedro and Villa were wide attackers in the way Guardiola wanted. Ferdinand described them as “the real killers”. They played their part in killing United in how they pinned the back four back, while Lionel Messi and the midfield constantly drew them out. That took an extra level of tactical discipline.

“That was the way under Pep, like clockwork,” Pedro says. “You make the movement, there’s the ball.”

If Barcelona had evolved, though, United had receded. There was a sense of Ferguson just keeping the remnants of the 2006-09 side on track, almost persevering through his own force of will.

“We were on the back end of that era,” Rooney told Carragher. “[Cristiano] Ronaldo and [Carlos] Tevez had gone and Rio and Vidic were a bit older.”

As with so much else in this game, and at that time, all of this was centred around one man. It wasn’t Guardiola. It was the bona fide great he had moved to false nine - Messi. Still just 23, the Argentine was at that point at one of about four different peaks his incredible career has offered. This was perhaps the one that was most frenetic, when he was almost a sonic blur of energy. There was one moment in the first half when Messi spun Park Ji-Sung one way before spinning him the other way, before immediately doing the same to Vidic. The change of direction was almost too fast to handle, especially with the way Messi would so quickly burst from the tip of midfield to the brink of breaking an entire defence open. United’s centre-halves never figured out how best to face him.

“We never got to grips with Messi at all,” Ferdinand says in his autobiography. “He played from deep but if I went chasing him, I’d leave a hole for their midfielders and wingers to exploit. Should I stay or should I go? I never knew.”

Such doubt was only contrasted by the utter certainty in the Barcelona dressing room. That is illustrated by the first words Guardiola said in his final team talk.

“I know we are going to be champions,” the Catalan proclaimed, his sleeves rolled up. “I have no doubt about it at all.”

Guardiola knew exactly how he wanted to play, exactly how he wanted to prepare, and exactly how he would respond to any United switches. This alone reflected the differences in quality that would become apparent during the game. Barca were just more advanced.

For the build-up, though, Guardiola almost completely concentrated on always having an extra man in midfield. Sergio Busquets, Xavi, Andres Iniesta and Messi formed a “magic square” into which United’s chances disappeared.

“In midfield, we will be four against three,” Guardiola said in that final team talk. “Here is where you are going to win the game for me.”

There were also focused technical insights to go with that tenacity of feeling. Guardiola pointed to how high Antonio Valencia plays, how Park always makes diagonal rather than straight runs, and how United had started to take short corners - so it was better to concede none at all.

“Everything he said would happen, happened as he said it would,” Javier Mascherano told Guillem Balague for ‘Another Way of Winning’. “During the match I was thinking ‘I’ve seen this already - because Pep has already told me about it’.”

Guardiola did have one surprising call, that was done to jolt his players emotionally, to help foster that intensity that really elevates such occasions. That was to play Eric Abidal, just 71 days after an operation to remove a cancerous tumour from his liver. There was an electricity around the dressing room when Guardiola announced it, an hour before kick-off. As the players then went out, the Catalan implored them to do it for Abidal.

“We cannot let him down!”

***

The first 20 minutes set the pieces in place for the entire game, in a far more profound manner than other matches of that magnitude.

Fired by Ferguson’s inspirational talk of winning the final the right way, United did come out in a frenzy, that had initial impact.

Mascherano resorted to simply whacking one ball clear, while goalkeeper Victor Valdes was forced into a pass that went way past Abidal. It was an unusual sloppiness for as composed a side as Barca. It was also a fairly typical adrenaline rush for such a fixture from United. Ferguson would later criticise some of his team for “playing the occasion”. Rooney told Carragher he quickly realised the approach wouldn’t work.

There just wasn’t sufficient co-ordination to the pressing. For almost every Barca pass from the back, one player - like Ryan Giggs or Rooney - would hare forward, only to leave 20 yards of space in behind. This was where the magic square would conjure dazzling spells of possession.

The brutal reality was that Ferguson was facing a more sophisticated level of football. This isn’t to necessarily blame him. United really required the type of triggered pressing that is widespread today, but was at that point only first being honed by Jurgen Klopp at Borussia Dortmund.

Barcelona were just playing a game ahead of its time, and above the field. They were also so well calibrated that little shifts in response to what the opposition did could have major effects. Against that early pressure, Xavi just dropped back 10 yards, and ensured United didn’t know who to press. Barca simply began to play through them.

There was a warning within 15 minutes. Busquets caught United’s forward line flat with one pass straight through the centre for Messi. Carrick was tight on the playmaker at that moment, only for Messi to instantly turn and leave him for dust. Ferdinand attempted to hold the Argentine off by holding his own position, but this was where the wingers came in. Or, rather, out. Villa stayed wide to draw Vidic out, allowing Messi to slide a pass between the two centre-halves for the forward to immediately return it. The ball back across evaded Messi by millimetres. The gaps across the pitch were getting bigger.

Chaos started to break out. Ferdinand turned to the sideline and asked Ferguson what he was supposed to do - step up on Messi or stand off. The manager would later criticise his centre-halves for not pushing on top of Messi, but they felt that was impossible. It would just leave the space from which it could get embarrassing.

This was that fundamental problem completely illustrated. No matter what United did, there was always a space left free, and a Barca star to exploit it. There was just too much to cover. United needed extra bodies creating a blockade. They were always a man - often two men - short. They were soon a goal down.

This move was really the game summed up. On 26 minutes, Edwin van der Sar attempted a long punt up, in the manner he had been instructed in order to maximise United’s superior physicality. Gerard Pique this time won the header, though, with Xavi collecting the ball to work on to his eternal partner, Iniesta. Carrick had been following Xavi, but this time felt close enough to Iniesta to intercept. The United midfielder had fallen into a classic trap, that he had set himself so many times. What really elevated these absolutely elite midfielders was not just that they passed perfectly, or through you. It went even deeper than that. There would be a psychological manipulation to the pass as much as a technical manipulation of the ball.

The delivery would be so intricately hit that it would invite an attempt at an interception. It would always, always, be sleight of feet.

“Xavi would pass the ball to Iniesta at a pace that encouraged you to think you were going to win it,” Ferguson wrote. “And you were not going to win it, because they were away from you. The pace of the pass, the weight of the pass, and the angle, just drew you into territory you shouldn’t have been in.”

Carrick maybe shouldn’t have been so easily deceived. He had often precisely done this himself with Paul Scholes.

“It’s about thinking how to drag the opponent out of position… posing a question,” Carrick wrote. “Me and Scholesy played an extra three or four passes just to work them, basically, a little game within a big game. We might not get any joy from that but, five minutes later the opponent might think ‘my legs are tired’ or switch off completely.”

This was precisely why, as in virtually every Barcelona game of that era, the two players with the most passes between each other were Xavi and Iniesta. It’s death by a thousand cuts, or in this game 777 passes. Most spread out from the 60 played between Xavi and Iniesta.

Here, Iniesta played a quick one-two with Busquets, before again giving it to Xavi. As a consequence just four simple-looking passes, Barca had unravelled United’s midfield and created a situation where it was four on four.

This was also where Messi’s movement and the wider players’ discipline were so disorienting. The centre-halves had the same problem as before, not knowing whether to stay or press. Messi himself stayed, meaning Evra was drawn to him, particularly as Pedro and Villa suddenly darted inside. This - to quote Ferdinand - was why they were the “killers”. The flanks were now free.

“You can see the design of that move,” Pedro says. “There’s first of all a movement of mine inside, where I can bring the defence and open the space outside. When you have players like Xavi or Andres who can give you those passes, well, you find yourself alone in front of the goalkeeper.

That’s exactly what happened. Pedro went one way then the other, allowing Xavi to pick what looked the easiest of passes. It came from movement United found too complicated to deal with.

“After that, it’s all about the finish.”

Pedro wrong-footed Van der Sar to put it into the corner and put Barca into the lead. As the forward ran away vigorously punching the air, Vidic turned to Evra to ask him what he was doing.

This was to prove another apparently small moment with huge consequences, and another way that Barca played on your minds as much as they just played exquisitely.

That was itself to be important, because Barca were not yet clear. They were actually pegged back just seven minutes later, from one attack largely maximised through individual inspiration. Rooney played an instinctive one-two with Giggs and smashed a brilliant finish past Valdes.

He celebrated with anger, but the truth was he was already irritated by how the game was going.

“I did not think we had any chance of beating them,” Rooney told Carragher. “Even when we made it 1-1 before half-time, there was no other game I played for Manchester United where I was thinking ‘there is no way we can win the game.’”

That feeling went right through the squad, as was illustrated by the half-time break. There wasn’t relief. There were only arguments. Vidic immediately started roaring at Carrick because he felt the midfield were leaving the defence exposed. Carrick insisted the defence had to step up. “We can’t do both!”

This was again the problem. United’s players had too much to do and cover in this system. It was why it was surprising Ferguson didn’t change it at half-time, having been given the reprieve.

He later admitted he “made an error at half-time”. He insisted they kept pressing, to keep going. Guardiola meanwhile insisted Barca keep doing what they were doing. The pattern of the game had been set by that first 20 minutes.

The legacy of the game was to be set by the next 20 minutes. It is no exaggeration to say that spell is one of the most special periods of football ever played by any team. This was art, and ascension. So much came together, from decades of football philosophy to three years of work, and little moments from this game.

Barcelona took it to another level. They were now passing the ball around at a pace that was picking United apart rather than just moving them at will. Holes were appearing everywhere.

On 53 minutes, another sharp series of passes left Barca with a three on two in midfield. Messi had the ball 25 yards from goal, right in the centre. In front of him, Villa had pulled back Ferdinand and Vidic, with Evra set to run out. So visibly mindful of what happened for the first goal, though, the left-back was too hesitant. It left Messi with too much space. He drove the ball past Van der Sar from distance, the ball swerving away from the goalkeeper and into the bottom corner.

The strike was true enough, but the celebration made it all even clearer. Messi ran to the corner flag and kicked it, abandoning himself to emotion. Barca were giving everything to the game, that was almost flawless.

There were moments in the spell after this when Valencia and Javier Hernandez were so exhausted chasing passes that they just fell into the back of Barcelona players

“We had turned Wembley into a huge rondo and there was nothing they could do about it,” Abidal said.

There was even less they could do about Messi. He was coming into his own, in a final that was virtually a career performance. It was an individual display that has almost been underappreciated, but only because the team display was so complete. On 68 minutes, Messi had the ball on the right wing, surrounded by two United players. He freed up that entire flank with one flick of the foot, before driving into the box. Nani just managed to poke the ball away as Messi was about to shoot, but the ball merely found its way to Villa. He found the top corner with the finest finish of the game, an exquisite curled shot.

That was it. That was enough, as Rooney said. The match was won. The Champions League was lifted. The entire game had been raised to a new level. The United players realised that, as did their manager.

“In my time as a manager I would say, yes, this is the best team I’ve faced,” Ferguson magnanimously stated afterwards. “They play the right way.” They played as Guardiola wanted.

“We tried to play as well as possible and we would like in the next 10, 15 years that people remember this team - I don’t know one of the best - that they enjoyed.”

Behind the scenes, the perfectionist in Guardiola wasn’t so purring. He pointed out some issues to staff, areas that could have been improved.

They couldn’t believe it, but that was the mindset that created football that people couldn’t believe.

An irony is that Guardiola hasn’t yet reached that level since. He hasn’t lifted the Champions League since. Ten years on, that game remains the standard.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks