Alan Shearer connects Blackburn and Newcastle to football’s lost era

As two of Shearer’s former clubs meet in the fifth round of the FA Cup tonight, Richard Jolly salutes a No 9 whose goals and records meant more because of who he scored them for

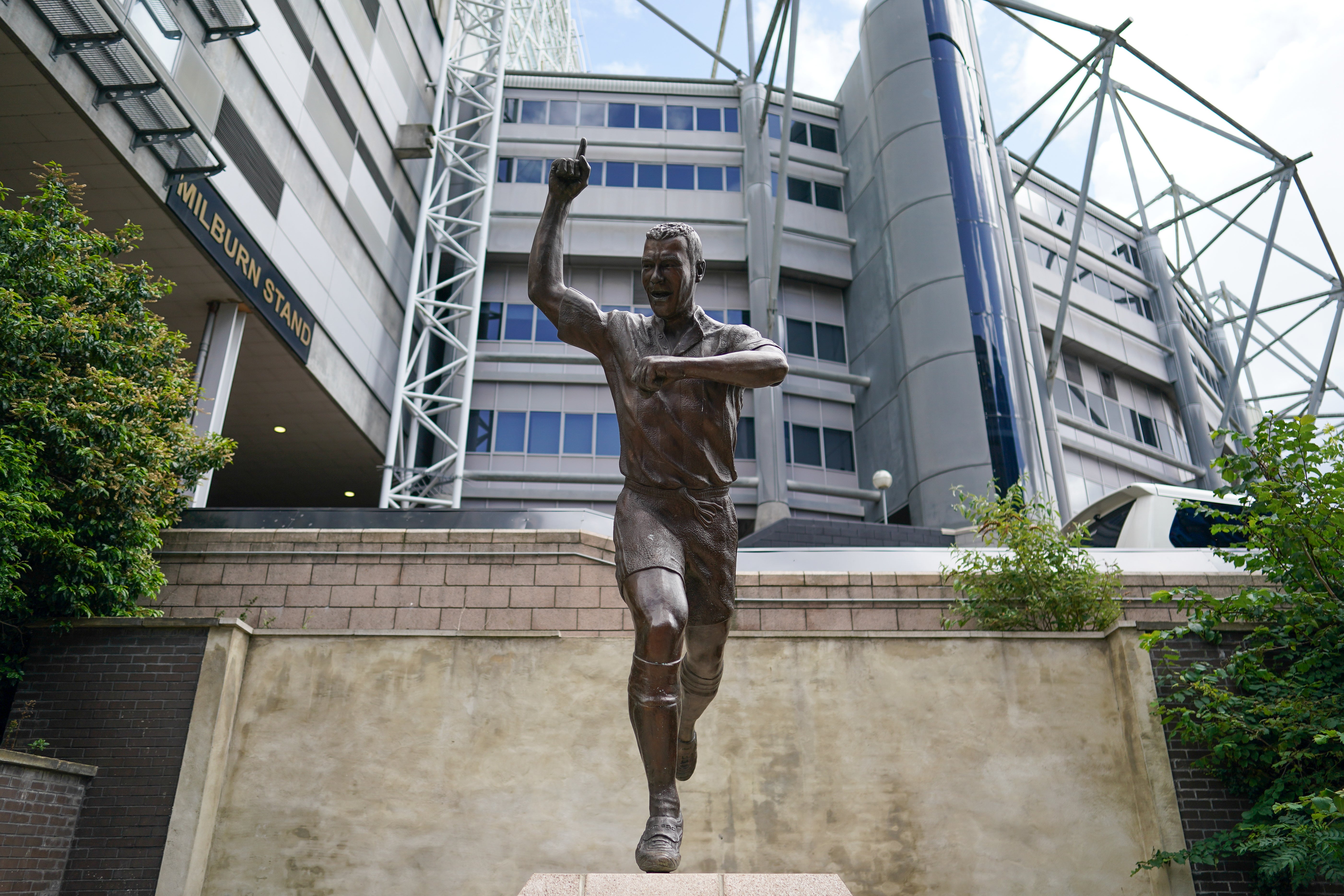

Alan Shearer’s statue is the best part of 100 miles from Alan Shearer Way. The former is famously just outside St James’ Park, a bronzed right arm up in trademark celebration which, it is to be hoped, he performed after all 206 of his goals for Newcastle United. But the road named after Newcastle’s local hero is on the other side of the Pennines, a stretch of A666 that runs past Ewood Park as far as Shearer’s Island; which, it has to be said, is a rather grandiose name for a roundabout.

Blackburn Rovers against Newcastle is a meeting of six-time FA Cup winners, but when they have not triumphed since 1928 and 1955 respectively. It is also the Shearer derby, a clash of clubs united by their love for a prolific No 9. Shearer became Newcastle’s record goalscorer, dislodging another prolific Geordie, in Jackie Milburn. He made history of a different sort with Blackburn: not merely with his scoring feats, but by making them champions of England for the first time since World War 1.

When Rovers dropped into League One in 2017, they were a still more anomalous presence on the Premier League’s roll of honour. A traditional club, founders of the Football League, were ahead of their time in one respect, accused of buying the title, but while both they and Newcastle were big spenders in the 1990s, smashing transfer records – Blackburn the British and Newcastle the world – to sign Shearer, the expenditure came in a different context.

Blackburn’s was funded by Jack Walker, the Lancastrian steel magnate, Newcastle’s by Sir John Hall, the Northumbrian property developer who oversaw the construction of the Gateshead MetroCentre. All of which, with Blackburn still unhappily owned by the Indian chicken firm Venky’s and Newcastle’s recent spending funded by the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund, feels like another era.

In a different millennium, Shearer was a front man for ambitious teams and projects alike. Symbolically, he joined newly-promoted Blackburn in 1992: his career took off with the start of the Premier League. He mustered 23 goals in 118 top-flight games for Southampton but has been the new division’s record scorer for virtually all of its existence, his tally of 260 looking safer as long as Harry Kane stays in Germany.

But, besides Walker’s largesse, with a new division, transfer fees mushroomed. Blackburn paid £3.3m for Shearer, which then seemed a colossal sum. His heavily pregnant wife was initially unimpressed. As they first drove around Blackburn, Shearer recounted last year, she said: “What the f*** have you done?” And if, perhaps in different language, the same question was posed of Kenny Dalglish, Shearer’s success showed his manager had the financial acumen to accompany his footballing knowledge.

Dalglish was always defensive about his spending. “When considering whether to buy a player, I always thought of his resale value,” he wrote in his autobiography. Many of Dalglish’s deals made Rovers money and they pocketed a huge profit when selling Shearer to Newcastle for £15m four years later. But there were three clubs in the relationship: Manchester United missed out on Shearer in 1992, expressing an interest but asking him to wait while Dalglish pounced. The striker met Sir Alex Ferguson in 1996. “At one point, I thought I was going to Manchester United,” Shearer said years later, but the allure of Tyneside proved too strong.

United, of course, did well enough without Shearer and there is a separate question if, had he joined in 1992, Eric Cantona would have been required. But he denied them a league title in 1995. He was potent from the start for Blackburn, scoring 22 goals in his first 26 games before snapping a cruciate ligament.

He returned even better. Only one player has scored at least 30 goals in three Premier League seasons: Shearer, in his last three campaigns at Ewood Park. Two were in title challenges, one for a side who limped in seventh.

“He was incredible,” his teammate Jason Wilcox recalled in 2020. “He could score every type of goal. He was extremely brave and courageous.” He was an extraordinary finisher. The later Shearer, reinvented as a target man at Newcastle, retained his hunger but lacked the pace of the Rovers version: he ran in behind defences more there, preferring to play off someone who could win flick-ons. The ‘SAS’ – Shearer and Chris Sutton were the title-winning double act, though he preferred partnering the unselfish Mike Newell.

Rovers’ tactics evoke another age, too: 4-4-2 with two wingers and a certain directness. But there was an effectiveness, too. Newcastle remain celebrated for Kevin Keegan’s team of ‘Entertainers’ but they actually scored 14 fewer goals in 1995-96 than Dalglish’s more pragmatic Blackburn had done in winning the league the previous campaign.

That remained Shearer’s lone trophy – the chances are that Gary Lineker will remind him he won the FA Cup with neither Blackburn nor Newcastle – but that one that owed huge amounts to him: he scored in 18 of Rovers’ 27 wins and four of their eight draws. “Blackburn’s critics accused us of being a one-player team,” Dalglish wrote. Which, as Rovers declined when he moved upstairs, was disproved in a way: Shearer kept scoring, but the team regressed. In 1999, three years after Shearer’s sale, without the one player, they were relegated.

After his glorious Euro ’96, he moved on, though Blackburn had offered the 25-year-old the position of player-manager in an attempt to keep him. Shearer has long insisted he had no regrets about picking Newcastle over Manchester. In the process, he turned down Barcelona, Juventus and Internazionale as well. He became the first English player since Jackie Sewell in the 1950s to become the most expensive footballer ever, a status he had for a year until the Brazilian Ronaldo displaced him. The tag scarcely seemed to trouble him: he scored 28 times in his debut season and won his third Premier League golden boot as Newcastle finished second, behind United.

In a decade at his boyhood club, he captained them in an FA Cup final and in the Champions League, scored more than 20 goals in six seasons, entrenched his position as the Premier League’s most relentless goalscorer; for those who prefer their statistics to date back to 1888, he is the fifth highest top-flight scorer ever in English football. Perhaps he was a bigger figure at each of Blackburn and Newcastle because he was a great player in what were not actually great teams; in some cases, not particularly good ones. But if the statue, the road, the island (roundabout) are forms of recognition, the goals mattered most. And for Blackburn and Newcastle alike, Shearer specialised in them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks