Cyclists may be using hidden motors to help on the hills

A tiny motor has been found in the bike of an aspiring world champion cyclist. But this clever device was never intended for cheats, its makers say.

Whatever she goes on to achieve in cycling, Femke Van den Driessche will remain a footnote in the history of the sport. After a race on Saturday, officials detected a secret motor in the young Belgian's bike. After years of speculation about “mechanical doping”, this was the first discovery of a motor in a sanctioned race.

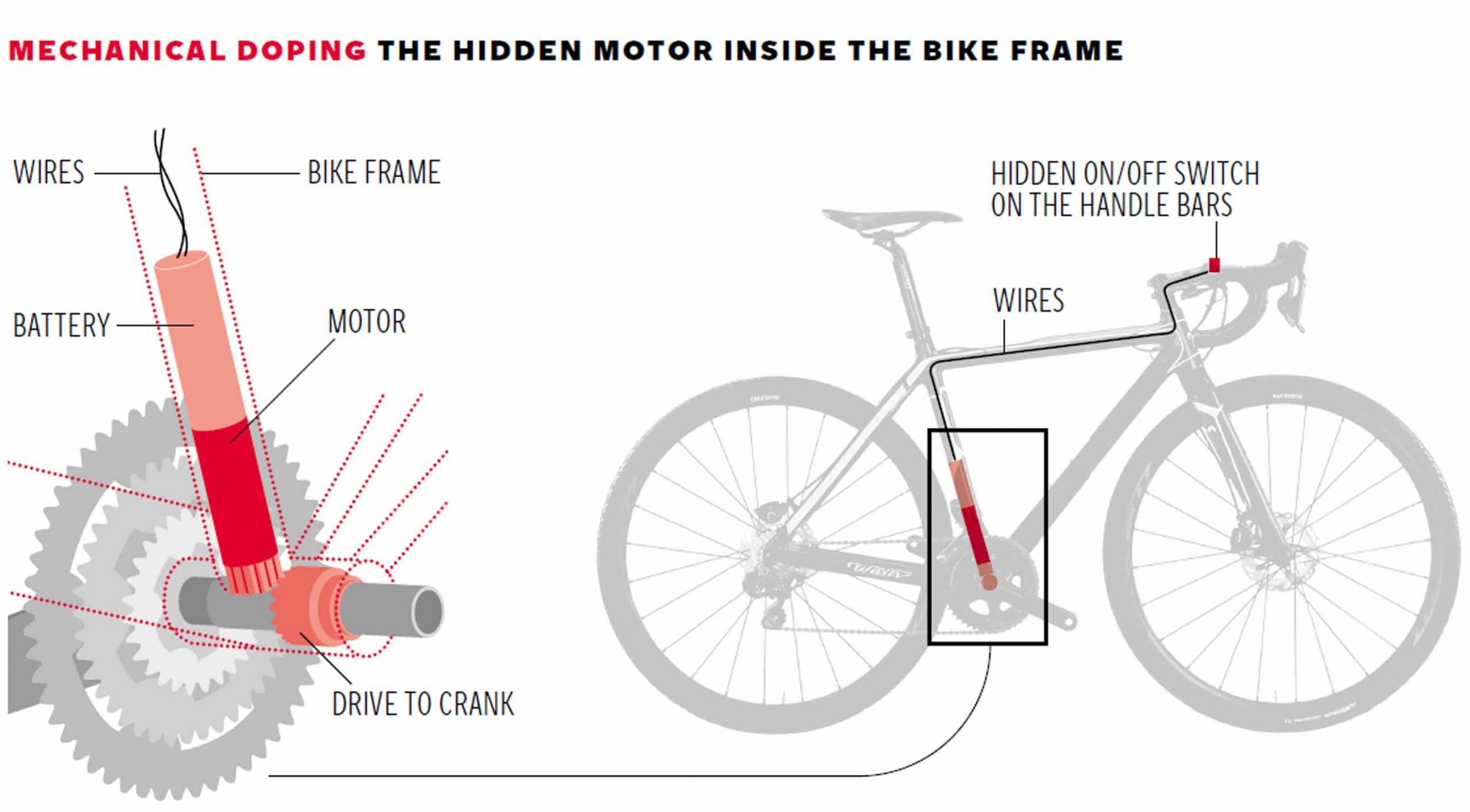

As it happened, the 19-year-old, who was favourite to win the under-23 world championship race in Belgium, snapped a chain and had to walk across the line. There was no stripping of medals. But a routine check revealed the device. Linked to a hidden button on the handlebars, the motors are designed to add bursts of power to the rider's pedalling.

Van den Driessche protested her innocence, insisting that confusion among her mechanics had allowed a “doped” bike identical to her own to make it to the start line (she told Belgian TV that she had previously sold the bike). “There's been a mistake,” she said, crying.

Regardless of what happens to the rider, the sport is now responding to the reality of a new kind of cheating as it continues to emerge from the shadow of pharmaceutical doping. If it wasn't all about the bike in Lance Armstrong's day, it kind of was on Saturday.

“I'm not surprised people are doing it, because it offers an obvious advantage,” says Michael Hutchinson, the retired British racer and author of Faster, a book about speed in cycling. More sophisticated testing is making it harder to get away with doping, he adds, “which could be pushing people towards motors”.

Burned by its failure to tackle doping during Armstrong's reign, the sport's world governing body, the UCI, woke up early to the threat of motors. In 2010, Swiss rider Fabian Cancellara rubbished rumours that he had used a motor. The UCI supported him but began to change its inspection regime. That regime went up a gear last year, when officials tested dozens of bikes, including Chris Froome's at the Tour de France. The UCI is now using Saturday's discovery as a warning. “We want the minority who may consider cheating to know that, increasingly, there is no place to hide,” its president, Brian Cookson, tweeted yesterday.

Any rider now caught with a motor in a big race will have to be particularly stupid, but the devices were never intended for them. The Austrian firm Vivax Assist began selling motors to cyclists 10 years ago, and was implicated in the accusations made against Cancellara. “We produce the motor for, for example, couples who want to cycle together,” says Ulrike Treichl of Vivax. “We also have customers who have health problems and want to keep up with a group. We don't want to help anyone cheat.”

Harry Gibbings, a British sports industry figure based in Monaco, is about to launch Typhoon Bicycles, which builds its own, high-end bikes with concealed motors. David Coulthard, the former racing driver, owns a prototype, which looks like any other premium road bike. “Due to his workload he can't always train as much as he wants to,” Gibbings says. “But with his Typhoon he can still stay with the professionals he rides with.”

Batteries can be hidden inside a disguised drinks bottle or pouch under the saddle. But Gibbings says the concealment only satisfies demand among cyclists who want to keep up on social rides. “Ultimately we just want to get more people on bikes,” he says. He has plans to move into the lower end of the market (Typhoon's high-end road bikes will cost more than £8,000). Gibbings says a motorised bike has no place in any organised ride. But even on an average Sunday morning in the Surrey Hills, do bikes with hidden motors not ride against the spirit of the sport? “It doesn't bother me,” Hutchinson says, “but I think the general feeling in Britain is probably that it's not quite cricket.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks