Robin Scott-Elliot: Don't mention the fixing or the absentees

Certain reputations remain in limbo, as must that of the sport itself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Andrew Strauss has entered the lair of the toothless tiger. Next week England will play their first Test since becoming the best in the world according to the official rankings. Their opponents are Pakistan, the venue the Dubai International Cricket Stadium, which stands not far from the offices of the International Cricket Council, the organisers of those rankings and the target of the England captain's considered reproach.

The ICC might have been tempted to fiddle its fixture list as a meeting of these two, when the Test game is on an encouraging and enjoyable high, is loaded with more baggage than a Heathrow carousel. England and Pakistan have history – a large part of which actually consists of some breathtaking cricket – but it is the excess, and recent excesses in particular, that weigh down the fixture.

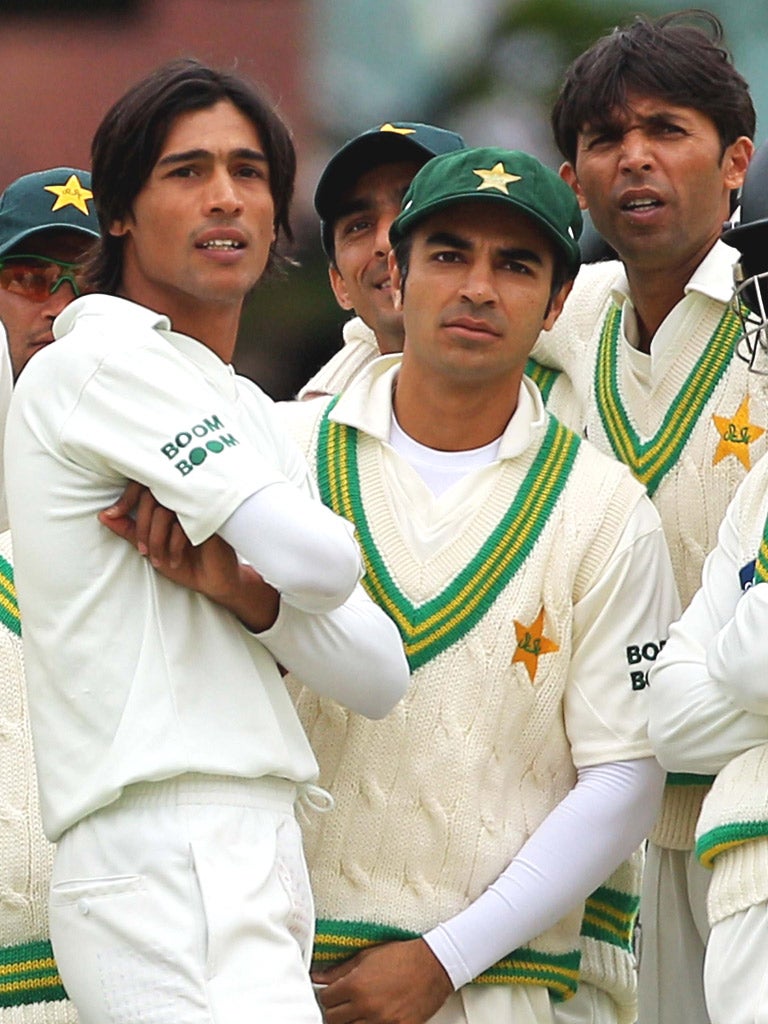

This already has the air of the Basil Fawlty series: don't mention the spot-fixing. Don't mention that three men who would have been key performers will instead be sitting in British prisons, and certainly don't mention that there are two players in the Pakistan squad who were also supposed clients of Mazhar Majeed, the convicted trio's agent, who was also jailed last November, and whose names featured during the trial.

The ICC, it should be said, has seriously sought to combat the scourge of fixing that has been a grim threat to the sport for two decades now. Other sports have looked to cricket's example when considering how to address match-fixing, which is overtaking doping as sport's public enemy No 1. The jailing of the three players was a significant moment, but it is also significant that cricket's governing body played at best a minor role in what happened in Southwark Crown Court. The ICC's attitude, certainly its public stance, since has not confronted a problem that will not go away. The illegal gambling market is estimated by Interpol to be worth an annual £500m in Asia alone and is unlikely to be resting on its ill-gained laurels.

Cricket is not the only sport threatened. Football's authorities are increasingly concerned – Fifa's life ban for six referees involved in helping to fix two friendly internationals stands as a more impressive response than the punishments handed out to Salman Butt, Mohammad Asif and Mohammad Amir by the ICC. Butt, as captain, should have been banned for life. The Olympics has recently been highlighted as a target for fixers, while tennis too has been on the receiving end.

For cricket it is a problem centred on Asia, where the bookmakers are based in places like Singapore, Mumbai and Karachi, but it is by no means only an Asian problem. The bookmakers have London links, while during the cricketers' trial there was evidence of a party based in Dubai closely involved in fixing.

That it is not only an Asian issue, or indeed one confined to the Pakistan team, will be alleged in London this week when Mervyn Westfield, the former Essex bowler, goes on trial at the Old Bailey on similar charges to those levelled against Butt, Asif, Amir and Majeed. Westfield is accused of taking money to bowl poorly for Essex during a Pro40 match against Durham in 2009. He denies the charges.

Like the previous trial, this is not a case based on action by the sport's authorities. The England and Wales Cricket Board has set up its own anti-corruption unit and the former policeman who heads it has said that it would be "naïve" not to think there is fixing in the county game. No mere cricket authority can combat illegal gambling run by criminal gangs with international reach – the ICC is shortly to meet with Interpol to discuss closer cooperation – but what can be done is to deal properly and fairly with the cricketers themselves, ensure they are educated, protected and made aware of the punishments that will follow if they betray their team-mates, their supporters and their sport. Clarity is vital, which brings us back to England's looming series with Pakistan and, in particular, the possible presence of Wahab Riaz and Umar Akmal.

The names of both featured in the spot-fixing trial. Majeed, the British agent, said they were among his clients. They have strongly denied wrongdoing. Akmal has denied even knowing Majeed, a close associate of his brother Kamran, Butt's vice-captain. Riaz, a talented fast bowler, has not played a Test since last May. When he was chosen for the squad to face England it was described as a return following "an unexplained six-month absence". The Pakistan Cricket Board, having given no reason for not choosing him, said that it had sought assurances from the ICC over selecting Riaz. It did not take long for the ICC to respond, saying the PCB's choice to pick the 26-year-old was nothing to do with the ICC. Selection is a national issue, was the gist of a statement by Haroon Lorgat, the organisation's chief executive. So nothing has been done to clear the dark cloud that hangs over Riaz.

During the trial the prosecution suggested the roles of "Wahab Riaz and Kamran Akmal raise deep, deep suspicions". After the trial ICC investigators were handed the evidence the Metropolitan Police had gathered. Kamran Akmal has disappeared from the Pakistan squad – again unexplained – but others, like Riaz, remain. They have not been charged, let alone condemned, but then neither have they been publicly cleared; their reputations remain in limbo, as must that of the sport itself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments