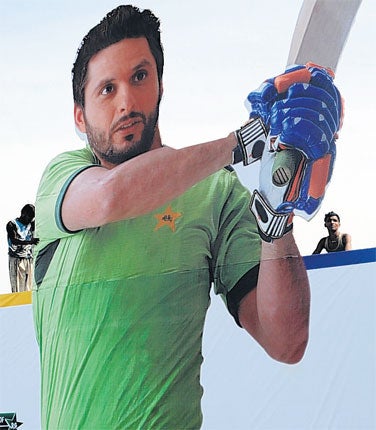

From motley crew to smash hits: how Pakistan became real Cup contenders

Shahid Afridi's side have shone thus far despite their recent problems. West Indies beware, writes Stephen Brenkley

Your support helps us to tell the story

As your White House correspondent, I ask the tough questions and seek the answers that matter.

Your support enables me to be in the room, pressing for transparency and accountability. Without your contributions, we wouldn't have the resources to challenge those in power.

Your donation makes it possible for us to keep doing this important work, keeping you informed every step of the way to the November election

Andrew Feinberg

White House Correspondent

With each passing match, evidence mounts that Pakistan can win the World Cup. Of course, this being Pakistan, it may, as it were, be unmounted with equal conviction.

But a team that by any normal sporting criteria should have no prospects are somehow assembling the form, class and nerve required at precisely the right time. Moreover, they appear to have discovered a unity of purpose the lack of which has so often cost them dear.

In defeating Australia on Saturday night, an event that had not happened in a World Cup since the last millennium, 35 matches previously, they produced sterling qualities, verve combined with intent, and resolutely refused to take their eye off the finishing line to win Group A.

Nobody would be entirely surprised if they were to mess it up against West Indies in Dhaka tomorrow but the indications are the cornered tigers are fighting again. As Misbah-ul-Haq, one of the veterans in a side blending grizzled experience and fearless youth, said: "I think it's always important for a skipper to listen to advice from his team-mates and that is something that Shahid Afridi is definitely doing.

"It makes the captain's job so much easier when the whole squad is behind you and everyone is pulling in the same direction. Generally decisions are being made by consensus and that's a good thing. Everyone is feeling involved and everyone is giving 100 per cent effort."

Neither Afridi, who was reappointed at the last minute, nor Pakistan would be universally popular victors but any progress from here is in the realms of the miraculous. Their cricket board is wholly symbolic of the current state of their country at large: on the verge of collapse.

This tournament was meant to be played in Pakistan as well as India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh in an improbable joint venture which was to re-establish the spirit of cricket in every sense. But the privilege of being joint hosts was withdrawn in the wake of the murderous attack on the Sri Lankan team coach on the way to a Test match in Lahore two years ago.

Since then the cricket team have lived a surreal existence. Allowed to play no home international matches of any variety they have become an itinerant, motley band travelling the world in search of a game.

Along the way, they have not always made friends even among themselves. On their tour of Australia last winter there were serious disputes and perpetual acrimony, the upshot of which was an unbroken sequence of catastrophic loss.

Last summer they came to England, who had sought studiously to befriend them in the corridors of cricket power, genuinely moved, it seemed, by their plight. MCC sponsored a two-match, neutral Test series between Pakistan and Australia with the theme of the spirit of cricket. There then followed a series against England.

Before the tour was done, three Pakistani cricketers had been accused of taking money to rig elements of matches by bowling deliberate no-balls. England, innocent bystanders, threatened not to play after being risibly accused of sharp practice and by the end the suggestion that the players were at each other's throats was not completely metaphorical.

The accused trio – the captain Salman Butt, the teenage fast-bowling sensation Mohammad Amir and another fast bowler Mohammad Asif – have each been banned for five years by the ICC. In May, they will face trial in London on criminal charges relating to the incidents in the fourth Test at Lord's last season.

It was hardly any surprise, therefore, that they arrived at the 10th World Cup in a state of disarray. After declaring their squad they declined to name their captain. Eventually they gave the job, with transparent reluctance, to Afridi, an archetypal splitter of opinions.

How they have managed to continue, at least intermittently, to play cricket of such high calibre is as much a mystery as how a country in such evident persistent turmoil can produce players who can perform so formidably. Amir and Asif would be huge losses to any side. Not that their progress has been entirely smooth.

Past indiscretions dating back to the early Nineties, added to the recent misdemeanours in England, always make it too easy to prejudge Pakistan. Matches with twists in which they are involved invariably breed suspicion and knowing winks. In the group match against Kenya it was to become widely known that a score of 40 could be expected after 10 overs. The score was indeed 40, the last three balls played back.

Coincidence is a plausible explanation but it always seems to be Pakistan. They remain capable of extreme vagaries of form. In another group match two weeks ago against New Zealand, they were in control until well past the 40th over, with New Zealand constrained and going nowhere quickly. The veterans Shoaib Akhtar and Abdur Razzaq then proceeded to bowl six overs of unmitigated dross which was dispatched high into the stands. There came 119 runs. It really could have been nobody else.

But Pakistan have survived and, propelled by some extraordinary bowling by the wizard of swing Umar Gul, have started to prosper. Afridi is neither a particularly popular captain in the dressing room nor an astute tactician. He is leading two former captains in Misbah and Younus Khan, who are clearly at the heart of some of the decision-making.

But his fast, attacking leg-spin has brought him 17 wickets so far. The batting has more often than not done enough and the blend has worked, beginning to feel like a selectorial masterstroke all overseen with weary pragmatism by their coach, the great former fast bowler, Waqar Younis. Umar Akmal, a potential batting genius of 20, calmly saw them home against Australia just when it seemed it could all go wrong again.

Pakistan, incidentally, had been the last country to defeat Australia in a World Cup, at Headingley in 1999. There were two survivors from that match, one on each side, Ricky Ponting and Abdul Razzaq. Then both sides reached the final, where Australia won comfortably by eight wickets. What happens now for Pakistan is, as ever, mired in uncertainty and probably controversy. But it would be unwise to take your eyes off them.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments