When Lloyd Honeyghan shocked the world and Mike Tyson with his sheer nastiness - Steve Bunce

ON BOXING

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a kid called Mike Tyson at ringside in a tiny banquet hall at Caesars in Atlantic City on the September night in 1986 when Lloyd Honeyghan won the unified world welterweight title.

A few weeks later, Tyson would win the heavyweight version but that night in the low-key, dimly lit room, against a backdrop of press and punter apathy, Honeyghan was ruthless. Tyson commented: “Lloyd doesn’t fight like a British guy, he’s mean and nasty.”

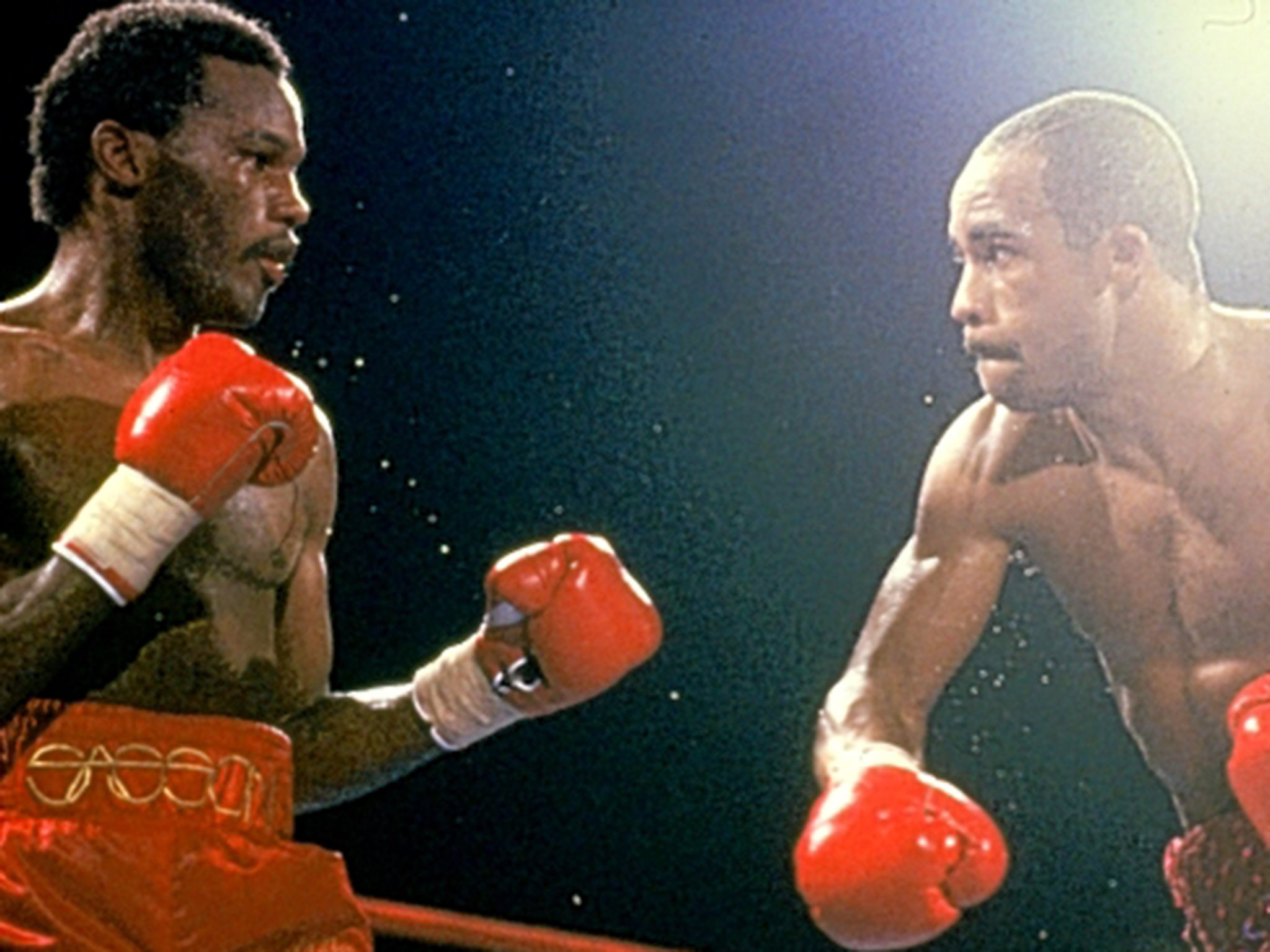

Honeyghan was 26, unbeaten in 27 fights, an angry underdog and the betting fall guy, selected as an easy touch for Donald Curry, who was a year younger and undefeated in 25 fights.

Curry was considered the best fighter in the world at that moment, but he was not an attraction and that is why the fight’s venue was so tiny, the hype non-existent and the programme just a hand-folded piece of A4 card.

However, Curry was linked with Marvin Hagler, the imperious, undisputed and seemingly indestructible middleweight world champion. There was much realistic talk of a $10m showdown.

Honeyghan was a gobby irritant, a south London nuisance in the thick of a rich plan and deep in a fighting city that was going head to head with Las Vegas for the sport’s biggest fights. At the time Donald Trump was holding court at Trump Plaza hotel in Atlantic City, desperate to turn the isolated metropolis by the ocean into boxing’s capital.

“I ain’t scared of anybody,” Honeyghan said before the fight, during a week of being dismissed, ignored and cast as the willing loser in Curry’s grand plan. “I will bash him up.”

Curry had struggled with the weight, losing 21 pounds to make the welterweight limit and allowing a glimmer of hope for the British boxer.

Mickey Duff, working the phones like a lunatic from his suite high above the Boardwalk, finally managed to get a bet on Honeyghan to win, staking $5,000 at 7-1 with a bookie in Las Vegas and then doing the same for his fighter. “The odds were good, I fancied Lloyd,” insisted Duff.

The fight was a bloody mismatch from the first bell and the great Curry was smashed from corner to corner. Honeyghan broke Curry’s nose, left him with a torn bottom lip and a cut above his left eye that needed 20 stitches.

At the end of round six the American’s cornermen waved the fight off and Honeyghan was the IBF, WBA and WBC champion. The tiny crowd was shocked and Bob Arum, the promoter behind the Hagler v Curry showdown, sickened.

“I felt for him [Curry] and now he will discover who his real friends are,” Honeyghan said the following morning. Curry’s career is a violent reminder, from that point, of the damage left behind once the cuts, breaks and welts have healed; he won and lost world title fights, fought on too long, went to prison briefly and was knocked out in three of his last four fights.

Honeyghan returned to London and led a procession of double-decker buses, taxis and fans down the Old Kent Road in south London. He defended, lost, won back and lost world titles in a variety of locations in a series of fights that all seemed to be packed with incident.

After regaining the world title in 1988 he fell out very publicly with Duff, the manager who stood by him in 1995 when he was kicked out of the gym in Canning Town, east London, run by Terry Lawless. Honeyghan said of Duff: “He looks at me as a pawn, a commodity. I don’t like him.” Duff responded: “Fortunately, there is nothing in our contract that says we have to like each other.” The pair continued to work together.

Honeyghan still appears on the boxing scene, head to toe in white fur, a cane in one hand and hefty shades hiding his thoughts. He is, like so many top fighters, a mix of living icon and eccentric, another ringside attraction for people to point their fingers at and snicker.

In all fairness, any man in a full white fur coat and a white fur hat sitting in a ringside seat at York Hall, Bethnal Green, should expect to hear a chuckle or two.

Tomorrow at Wembley a boxer called Frank Buglioni, nicknamed “The Wise Guy”, will try to add his name to the list of British underdogs who won world titles; Honeyghan’s name is at the very top of the list and Buglioni would have to pull off a bigger shock to beat Fedor Chudinov and win the WBA super-middleweight title.

Buglioni will need the nastiness that Tyson talked about in Atlantic City all those years ago. Honeyghan had it, and now we will find out if Buglioni has the same desire to shock.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments