Joshua Buatsi to follow Anthony Joshua's path to stardom, but will do well to recall Alan Minter and Anthony Ogogo

All are Olympic heroes but they have had to take different roads since turning professional

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

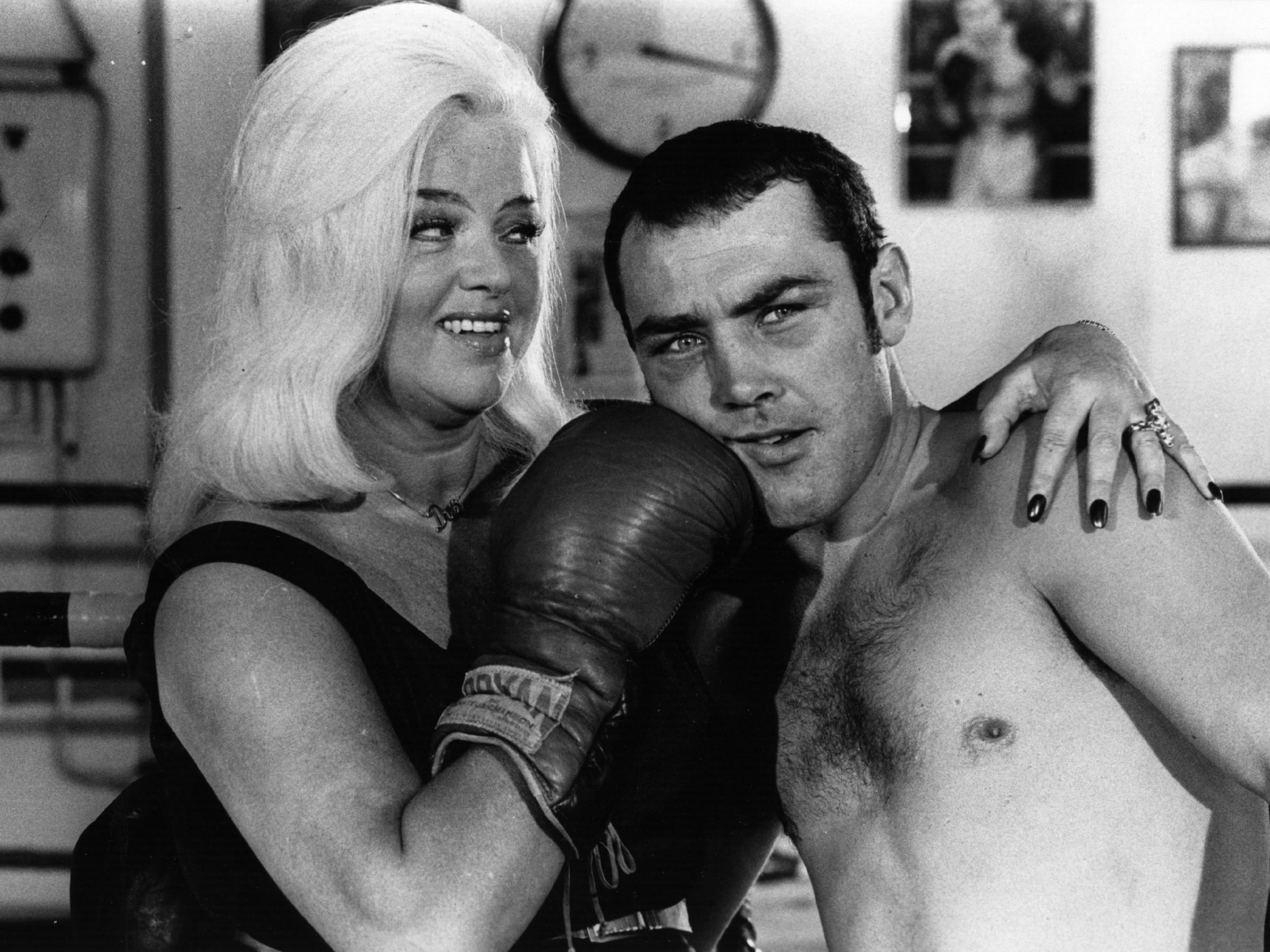

Your support makes all the difference.In 1972 Alan Minter returned from the Munich Olympics with a bronze medal, the sympathy vote from a vast television audience after losing a diabolical decision in the semi-final and just six weeks later in virtual obscurity his professional career started.

Minter was one of three British boxers to win a bronze, not the only one to get a bad decision, but he was the one that the fans liked, the one they remembered and the one they followed for nearly a decade. Minter won his debut, lost a few bloody scraps and after 43 fights and eight years he finally won the world middleweight title. Minter could, make no mistake, really fight.

“It was different then, very different,” said Minter. “I had to start all over again – no easy fights. They all wanted to beat me, no knock-over jobs back then, no easy nights.” Minter won his first 11, then lost four of his next seven and less than two years after glory in Munich his career was in genuine crisis because of the savage cuts he kept getting in brutal, bad-tempered brawls.

In October 1974, two years after turning professional, Minter and his opponent were thrown out for not trying, not fighting; the Olympic hero slipped to 14 wins, four defeats and one no contest. It is a record that would mean certain failure in the modern business.

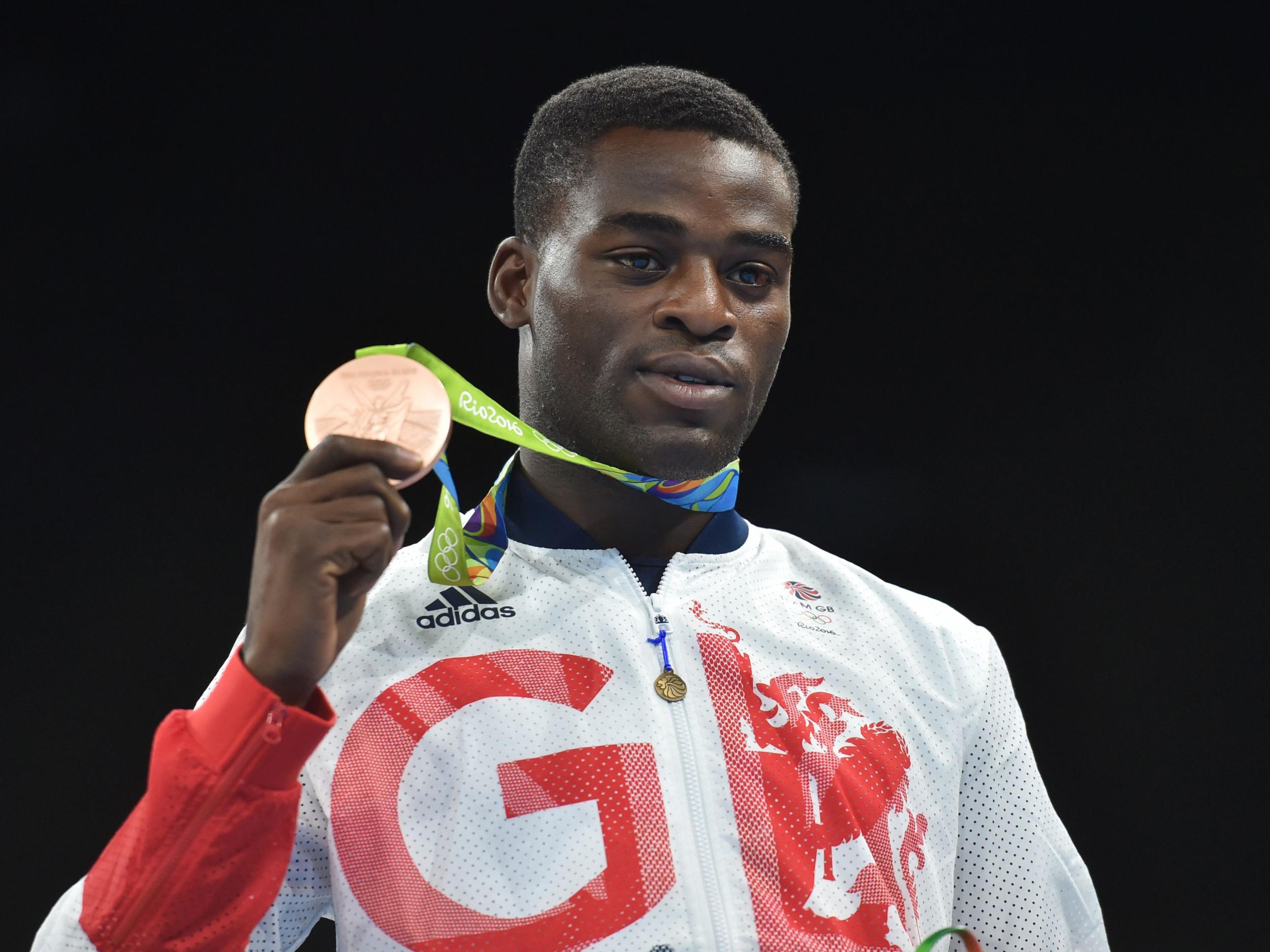

This Saturday, after nearly 11 months out of the ring, Rio Olympic bronze medal winner Joshua Buatsi fights for the first time as a professional in a business that is connected by just a few tiny threads to the pitiless fight game of the ‘70s. Buatsi will not lose four of his next 18 fights, he will not have 200 stitches sown into his face in filthy dressing rooms and he will probably not break a sweat for about two years. Buatsi can, make no mistake, really fight.

Buatsi has been a busy boy since winning bronze at light-heavyweight last summer, when he beat seeded boxers and exceeded expectation, reading over dozens of fight contracts, listening to promises, finishing his studies and waiting for the decisive word from his church. He is now part of Anthony Joshua’s management group, will be promoted by Eddie Hearn and will fight free of any pressure against a succession of men imported for their ineptitude. The British boxing business is a heartless place for losers at the moment with entire nights of so-called competitive fights nothing more than convenient, brightly illuminated slaughter.

Buatsi can be moved fast at light-heavyweight, the marketing in the modern business is done away from the ring and not inside the ropes, and there is no need to wait for the traditional slow process of genuine recognition or word-of-mouth to help build a fighter. Minter had to wait until his 25th fight before he got a British title fight and his 44th before he fought for the world title. It is doubtful that Buatsi will have many more than 25 fights and there is absolutely no chance that he will have anywhere near 44 fights. The modern business is still as dangerous as it has ever been but it is far easier and nobody seems to care about the gross mismatches.

However, there should always be a cautionary tale attached to any predictions of great fame and wealth in boxing and having an Olympic medal or vest is simply no guarantee. It was just five years ago at the London Olympics that Anthony Ogogo won a bronze medal at middleweight in some style; Ogogo did a deal with Golden Boy in Los Angeles, was draped in neon when he fought on a Floyd Mayweather undercard in Las Vegas and he biffed and bashed a few bums before it started to go wrong. Ogogo’s body collapsed on him and a severe injury list ruined his progress before a mysterious and shattering defeat in October of 2016. Ogogo still dreams, still hopes to enter the ring again.

Minter had a seemingly endless list of obstacles, Ogogo has a serious injury and both should be remembered in the coming months as Buatsi is draped in the glittering gown of splendour and hope as his fists send the hapless to the canvas. It’s the business, but it is not always simple.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments