A tale of sorcery and sadness: The tragic story of Herol Bomber Graham

From world title fights to stacking boxes in Asda and being sectioned with mental health issues: the sad story of a true British boxing great

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

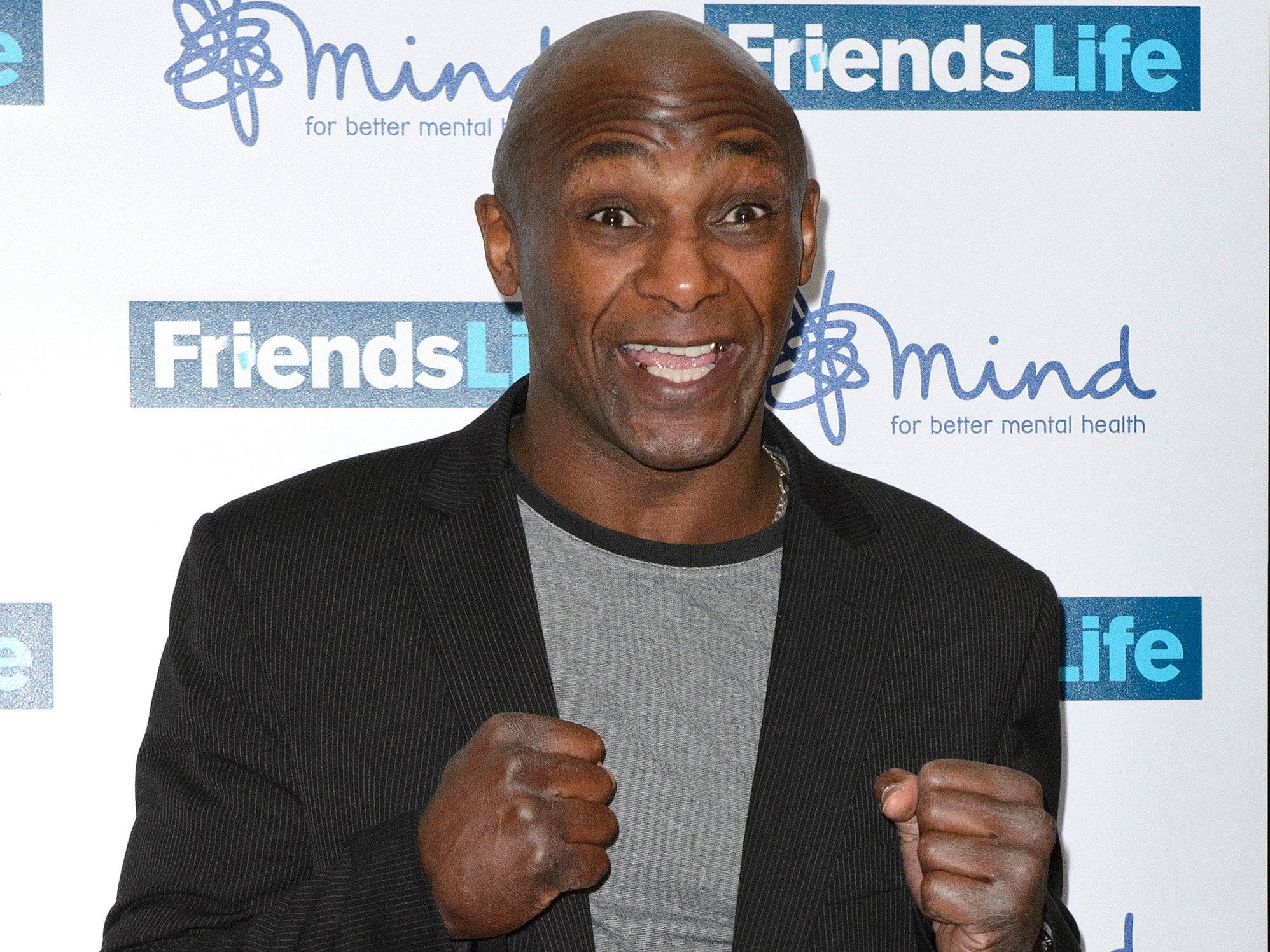

Your support makes all the difference.In the fighting life and times of Herol Bomber Graham there is a million-pound offer, a sickening punch, a glittering career, despair, collapse, attempted suicide and a stay or two in a mental health facility.

Graham is back in a locked room, sectioned again and even further away from his finest fighting days; he finished his boxing career long after his beautiful skills had faded, replaced by the bravery that left him in his present state. Sure, he easily passed the medical tests, was glowingly declared fit to box in the last years of his career. It was his ear, they said, when he stumbled and slurred. There was nothing wrong, they lied.

However, Graham had that truly brutal fighting affliction: he was ‘gone’, not a medical term but as damning as any diagnosis in a sport aimed at wrecking a man’s senses. Graham fought too long for the riches he was denied and deserved - perhaps he missed out on more than any other modern British pugilist. It’s a horribly cruel tale and now Graham sits alone, medicated and increasingly helpless in his failure. His story goes something like this.

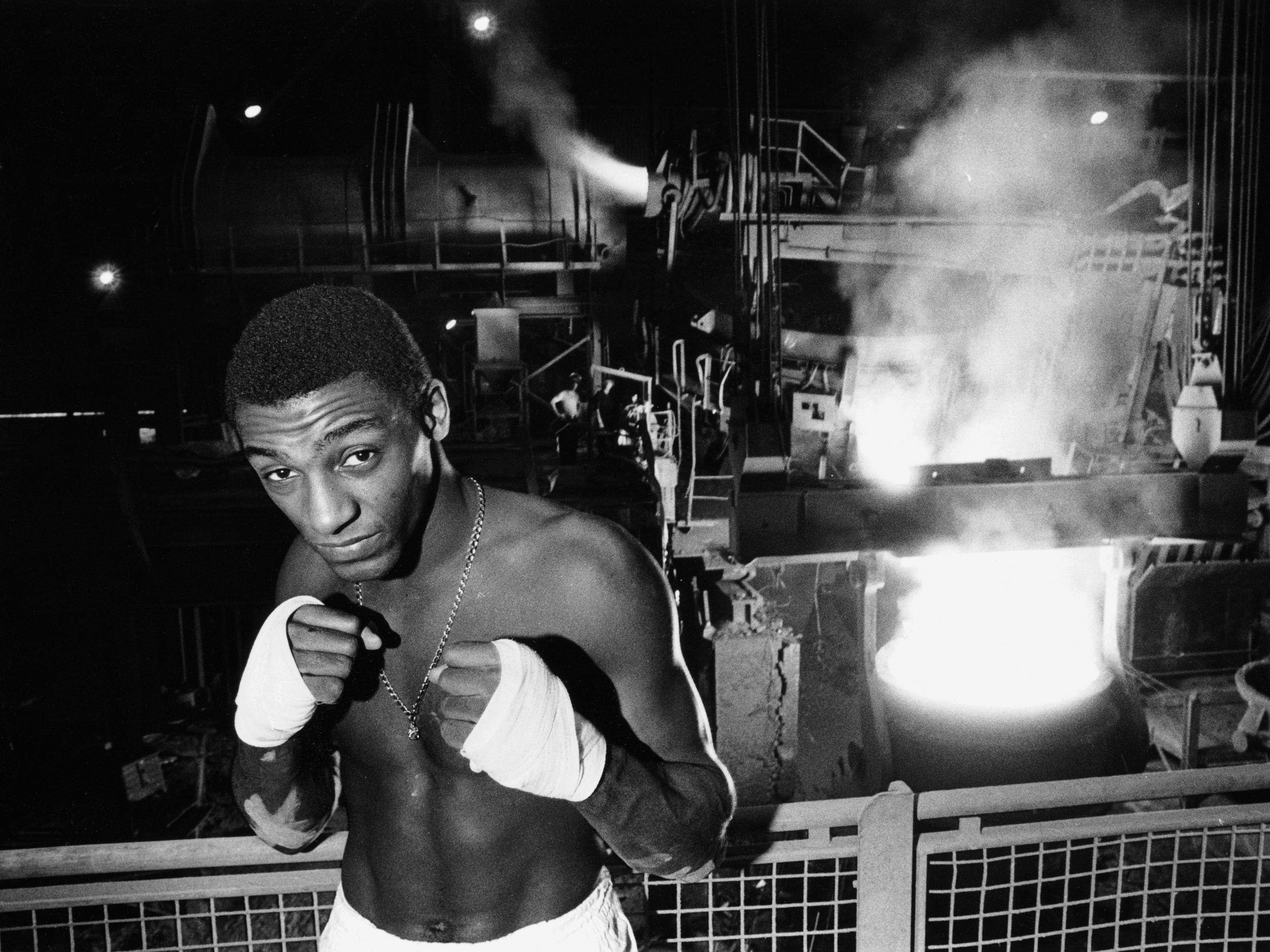

In 1978 at 18 he won the British amateur title, turned professional later that year, won the British, European and Commonwealth titles in an unbeaten sequence of 38 fights that lasted until 1987. Graham had the great whispering guru Brendan Ingle at his side, a unique and often frustrating pairing who refused to bow to Mickey Duff and his legal cartel. “It was hard to do business with them,” Duff insisted. “I wanted the best deal for my fighters and Duff never liked that,” countered Ingle.

“I would take Herol to the working men’s clubs and ask if anybody thought they could hit him,” said Ingle. “Then I would tell them that Herol couldn’t hit them! They all put the gloves on and loved it and they came out for the fights. Nobody ever hit him, never.” Graham won and defended his titles in Sheffield.

He was for too long the number one contender for Marvin Hagler’s world middleweight title; Graham stopped or knocked out 18 of the 24 men he beat during Hagler’s reign. Hagler and his people ignored Graham, even when Barney Eastwood, the Belfast bookie and boxing manager, offered the American a million pounds for a fight in January of 1987. In February Hagler was stripped and Graham still had to wait as the shameful series of delays continued.

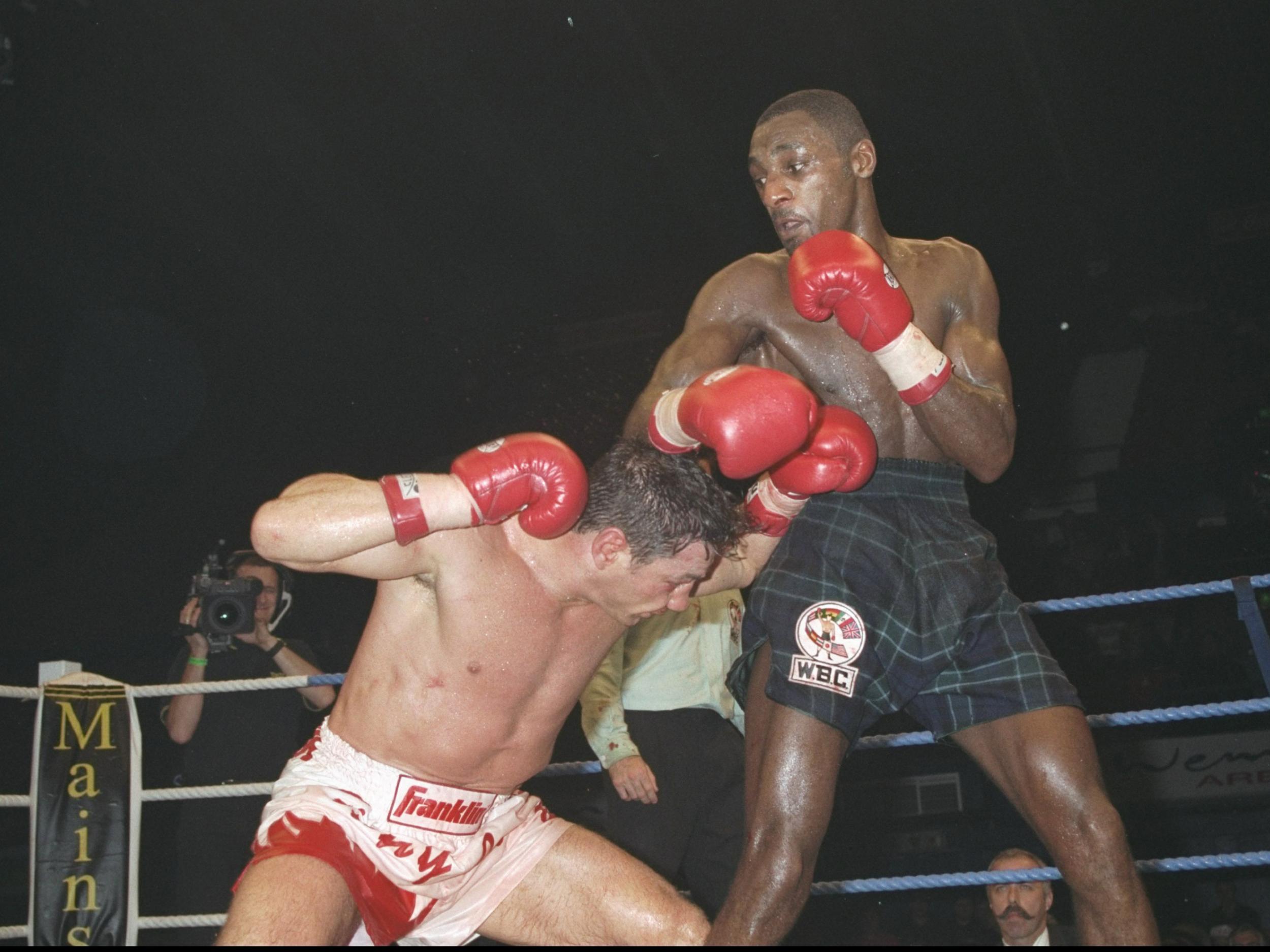

Sweet Herol lost for the first time in a bad-tempered, confusing brawl with the Italian Sumbu Kalambay in May of 1987. Ingle was not in the corner on the night. “I’d have won that fight if Brendan had still been in my corner,” Graham said and he was right. Kalambay got a tight decision, Graham boxed the wrong fight and five months later the Italian won the world title. Graham had to wait another two years before he got his chance.

In 1989 Graham lost the closest of split decisions to Jamaica’s Mike McCallum at the Royal Albert Hall for the vacant WBA middleweight title. Ingle was back in the corner but so was Eastwood and their arguing, contradictory advice, open hatred of each other left Graham in turmoil. “I looked forward to the round, so that I could have a break from their sixty-seconds of screaming,” Graham said. That sad night in London Graham was 29, had been a professional for 11 years and had lost just once in 42 fights. They are a set of statistics that will never happen again, a perfect storm of hardship, bad luck and cruelty.

By 1990 it was not just the American world champions avoiding Graham but the high-profile trio of British boxers Chris Eubank, Nigel Benn and Michael Watson all got on with their lucrative business without inviting Graham to the party. “Nobody wanted to willingly fight me, I had to wait and then take what was offered,” added Graham. There is not one solid story that I believe about Graham refusing a fight - he was just bloody avoided.

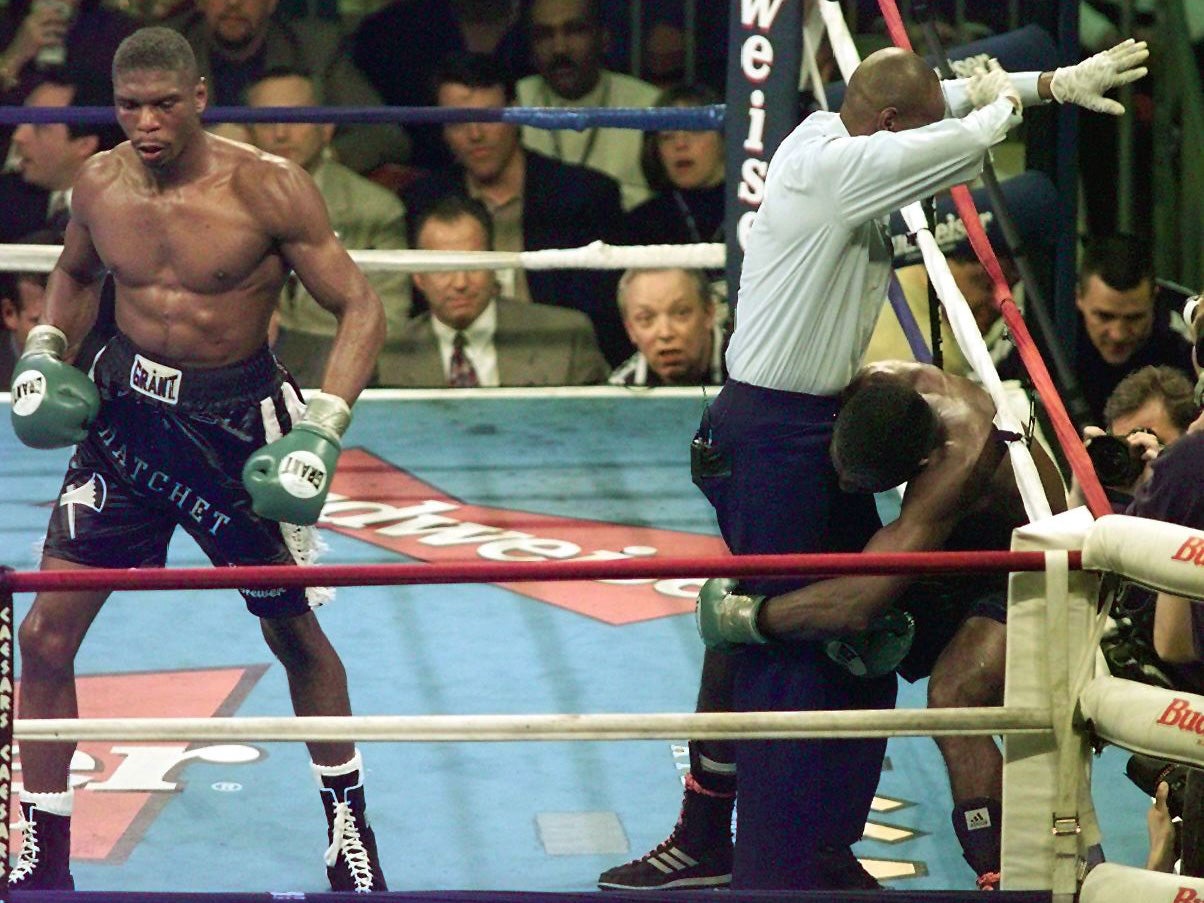

In 1990 Graham was just seconds away from winning the vacant WBC middleweight title when he met Julian Jackson of the Virgin Islands in Spain. Jackson had lost just once in 41 fights and had knocked out 38 of his victims. “I knew nothing about him, but I was told he was blind as a f****** bat,” said Graham. The fight was in Spain because Jackson had retina problems and could not box in Britain; Jackson struggled to touch Graham, looked pitiful, his left eye was closed and at the end of round three the doctor and referee told Jackson the next was his last round. In the fourth, Graham made one mistake, was caught and out cold before he hit the floor.

Graham had one more world title fight, his last night in the ring in 1998 when he was winning but ran out of steam against Charles Brewer for the IBF super-middleweight title. In Atlantic City that night there were tears in the dressing room, a rehearsal for the harrowing decades to follow. It was over, he finished with 48 wins in 54 fights during 20 years as a professional.

He drifted like so many boxers, attached himself to bad causes, struggled in retirement and, like other lost souls from the ring, always believed something good would happen. It seldom does - I could have told him that boxing takes so much and is reluctant to give back, and when boxers tell you the fighting is the easy bit they are not joking.

He was sectioned in 2009 after failing with brandy and a knife to end his life. In 2014 he was loading trucks for ASDA, getting paid eight-quid an hour. My cousin worked with him and tried to make sure that Herol did nothing. “It’s Herol Bomber Graham, he can’t do that work - he’s a legend,” he told me.

The last year has been harsh. Graham’s partner Karen has terminal cancer, they are skint and Herol had been sectioned once again. There is a page for donations, something for people to say they have done.

Herol Bomber Graham is the latest of the heroes I started writing about over thirty years ago to have a living obituary. A donation will help, but it is surely too late to change the life of one of British boxing’s modern treasures.

To donate to Herol Bomber Graham's JustGiving page, please follow this link

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments