Remembering Errol Christie: A sweet man who fought racism and deserves his place with the great British fighters

Christie was a brave man who fought against an often volatile backdrop and his bout with Mark Kaylor will live long in the memory — but ultimately spelled the end of his fighting dream

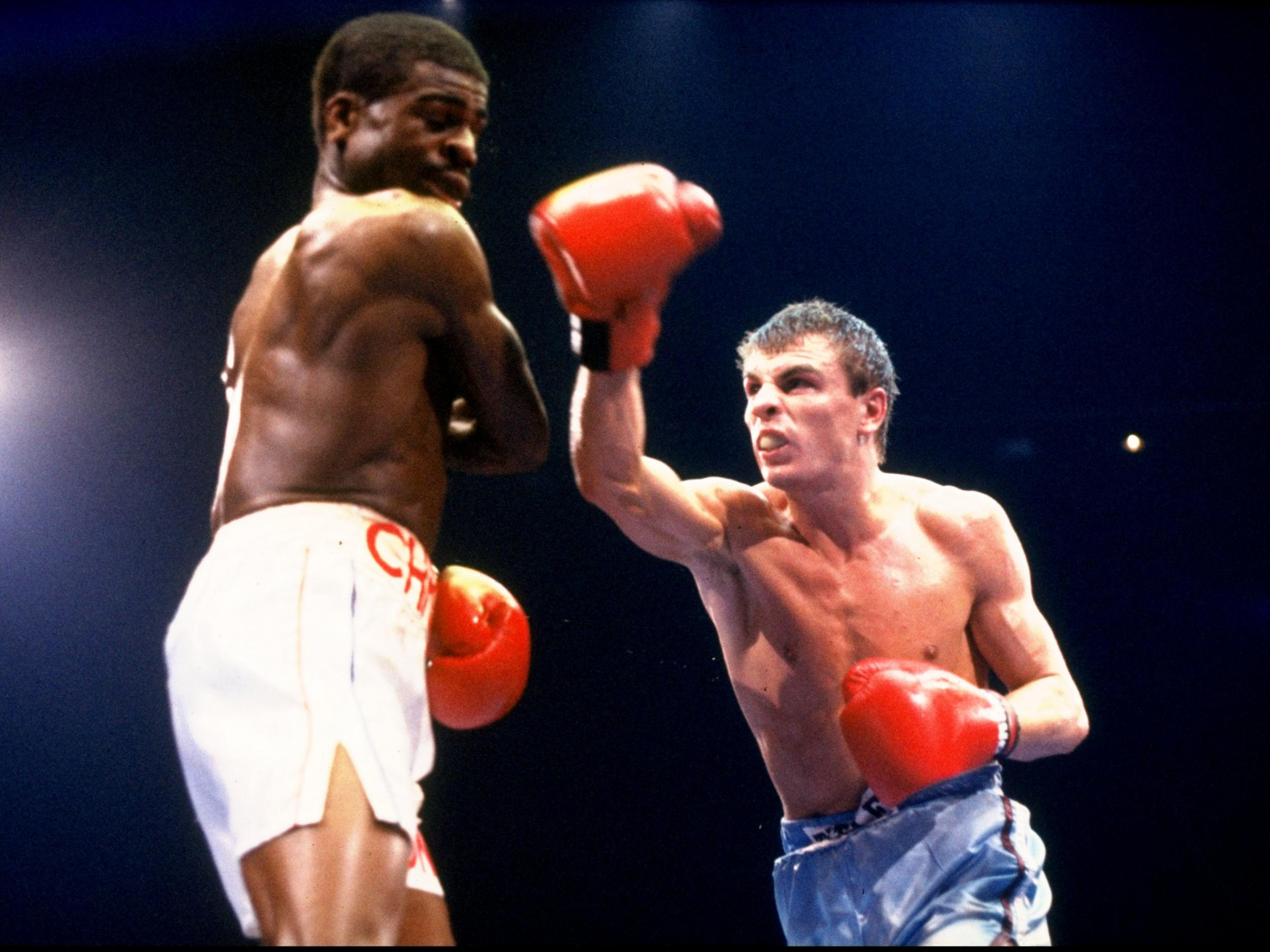

In 2010 Errol Christie spoke to his hated enemy Mark Kaylor live on a radio show and the pair, after circling politely for a few minutes, got right down to the business of their iconic fight in 1985.

“You called me an ugly black b*****,” Christie said. “I’m sorry for the things I said, I respect you, I always have,” replied Kaylor and added. “Why were we allowed to go nose-to-nose with nobody between us? Somebody never did their job.”

Christie was next to me in the studio and Kaylor was on the phone from his new home in California. This was their first meeting since the night at Wembley Arena in 1985 when they had fought against a volatile backdrop of racism and against the advice of the local police commissioner.

The fight, a final eliminator for the British middleweight title, held a nation gripped after the pair had fought on the street at the opening press conference and been forced to shake hands, kiss and be friends in a series of live stunts on breakfast television.

There was hate in the air and Terry Lawless, part of a legal cartel that ran boxing at the time and also Kaylor’s trainer, hired Cass Pennant, the black lord of the West Ham terraces, to secretly police the 10,000 fans at a sold-out Wembley. It worked, there was no trouble but the police were wild with anger at the covert troops operating under their noses.

In the opening round both boxers were on the canvas, a firework went off in the crowd, nobody heard the bell to end any round and Kaylor was over again in the third. “It’s like a fight on the cobbles, which is where they started,” said Harry Carpenter, on microphone duty for the BBC.

They carried on punching at the end of the fourth, in round eight Christie was down again, hurt, he crawled towards his corner and was pulling himself up on the ropes when Harry Gibbs, a referee so distant in time that he had served as a prisoner of war when captured in 1940, finished the fight.

Kaylor was exultant on the night, it was an event never to be forgotten and a fight that sweet Errol never fully recovered from.

Christie had turned professional in 1982, he was just 19 and he had won every tournament he entered, including a rare gold for a British amateur boxer at the European under-19 championships in East Germany. He still has a place in the Guinness Book of Records with his ten domestic amateur titles.

He was ITV’s Golden Boy, often in publicity shots – topless and waving a Union flag – with the channel’s light-entertainment and cheesy giants. He won his first 13, 12 by knockout before a shocking loss to a big Belgian; there were quick wins in a hasty recovery and then another unexpected loss.

The Kaylor fight was, not to be too dramatic, a must-win scrap and Christie’s defeat at just 22 was the end of the fighting dream for the kid from Coventry. “It was all I had ever done, every day since I was a small child. I never accepted it was over,” Christie said that night in 2010 when I gathered him, Kaylor, fight fixer Dean Powell and Pennant together to celebrate the 25th anniversary of their fight.

Boxers, especially the great ones that fail, never accept the end easily and Christie was dragged punching and kicking through eight more years of hope and pain before the brutal end one night in Manchester.

I was there for that, cried with him in a changing room as he sat glass-eyed, sweating and wondering where it had all gone wrong. It is hard to fully understand what failed expectation in the harsh world of boxing does to a fighter, and Christie’s final fight was reduced to just a tiny footnote on an anonymous show at the Free Trade Hall.

I gathered up the awful moment for my new book, a place where Christie gets far more than a tiny footnote about one night in 1985 or 1993: Errol Christie gets what he deserves, a place with the great British fighters.

After leaving the only life he had known Christie ran a market stall in south London, was a dreadful stand-up comic for a bit, put on an overcoat to stand on doors at dirty pubs and tried to work in schools, preaching about the dangers of knife crime, street-life and general stupid thuggery.

Christie and his many fighting brothers had skirmished with the National Front on the streets of Coventry during the late Seventies and early Eighties. Christie never ran from a single fight in his life, but he was not just a proud scrapper and he never turned away from a smile or an extended hand. People loved Errol, the nicest man they met.

In 2010 Christie and Kaylor ended the radio interview as friends, two broken fighting men swapping war stories, packed belatedly with love and respect. There was not a dry eye in the studio. “You know what, Mark?” Christie said. “We were both born too early – that fight would be worth one million each now.”

Kaylor agreed, they talked about meeting, then Errol slipped away to get a bus back to Lewisham. The pair had split a record purse for a non-title fight of £82,500, that night in the Wembley ring. They would get and deserve more than a million now.

Even the special police unit that jumped him in early 2015 liked him when they realised he was not the man they were looking for. He thought he had cracked a rib in the tussle, went to hospital, had an x-ray and was told he had lung cancer. This was truly vicious.

“It looks like the police could have saved my life,” Errol told me in late March of that year. As I said, he was a bad comic, but a lovely man. I went to see him on Friday, his room bright with sunshine at a hospice in south London.

Errol Christie died on Sunday night and I can guarantee that somebody that loved him was holding his huge hand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks