Barry McGuigan still desperate to let the punches fly as Carl Frampton prepares for the biggest fight of his life

Frampton will face Andrés Gutiérrez in Belfast this weekend, eager to bounce back from his first professional defeat in his first fight in Ireland in over two years

When Barry McGuigan was Carl Frampton’s age he had been away from the ring for nearly two years, away from the lights, the noise and the adoration of his fans. In 1989 it was all over for McGuigan at just 28 and he was left scratching about for a living.

It took McGuigan a few years to become a citizen after he left the ring, he moved inevitably through a selection of alternative careers; he had a stint racing cars, did a lot of punditry and fell in and out of various outings on the celebrity circuit.

At some point in 2009 he came home, he was back in the gym, back with the fighters and the filth and the people he really knew and people that really knew him.

In 2009 Frampton turned professional and McGuigan started converting people, talking to people in the fight game about his boxer’s potential and his belief.

It was not an easy job, McGuigan wanted to be independent, he wanted to be in control of the journey and not a bit player in a team, the third man in a tracksuit on the edge of the screen when Frampton walked to the ring; another retired fighter, picking up scraps to live for a few seconds each fight night in his old memories.

In the summer of 2009 at the Olympia in Liverpool, a redecorated vaudeville venue that was once home to a wondrous circus with camels in the basement, Frampton stopped a man from Hungary, dropping him three times before it was called off in round two and the journey had started.

McGuigan still sucks in the air each time he climbs through the ropes, greedy for that feeling he had when he was a five-stone scrapper on the youth circuit in Ireland, wearing a baggy vest tied tight across his tiny shoulders by a handkerchief.

There was even one night in 1993, at the King’s Hall in Belfast, one of the venues he graced so beautifully in a career that the city loved, when he was introduced to a small crowd and he ducked through the ropes to the roars only believers can make.

He nodded and then he shadow boxed for about thirty seconds. It was real shadow boxing, not that comedy routine that Conor McGregor recently tried at Wembley, not that showy combination rubbish that is for mirrors only and people that lie about their boxing.

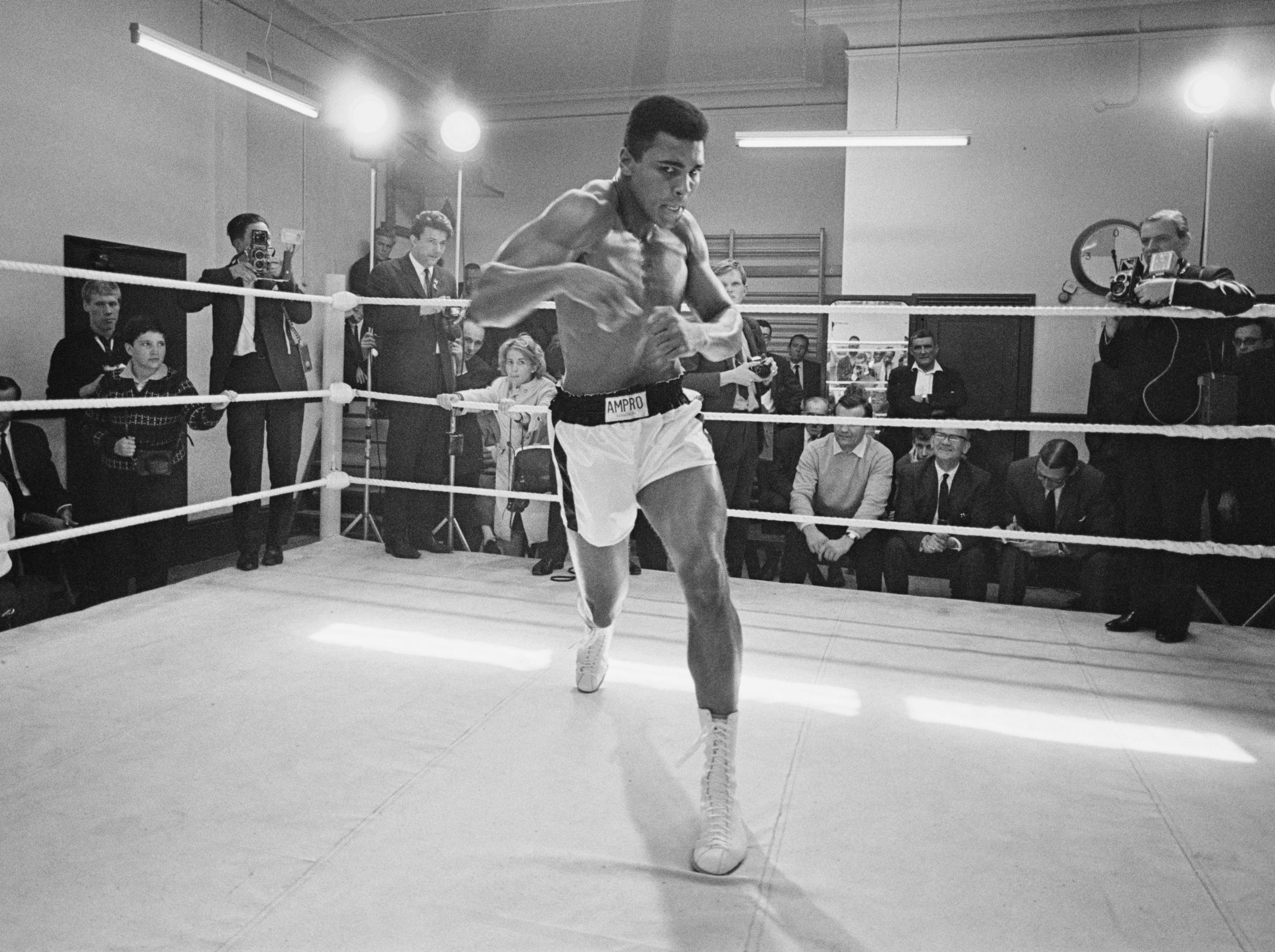

In the Belfast ring that night McGuigan was having a real fight in his mind, each move a replica of things he had done in that ring before and it was – for about 30 seconds – a pleasure to witness. I saw Muhammad Ali do something similar four years later at the Freedom Hall in Louisville when he was introduced from the darkness and somehow, at a time when he seemed to stumble silently from day to day, he found his magic feet, shuffled and flicked out boxing’s greatest jab.

Frampton kept on winning, started to look and sound like the fighter McGuigan had been promising. In 2013 he won the European title and in 2014 he won a version of the world title outdoors in the cold in Belfast.

It had to be Belfast where the politics and secret diplomacy had dealt with the violence that was a backdrop to McGuigan’s glory. Frampton was able to win the belt at home and not, like McGuigan, on the road – it was west London - in a piece of somewhere that was wholly converted by the travelling Irish.

McGuigan’s win at Loftus Road was during a night when priests fainted at ringside and pubs ran out of beer. “I’ve never met anybody who was not there,” the boxer told me. I agreed.

McGuigan was in the ring that night as Frampton prepared to fight Kiko Martinez for the world title, moving his shoulders, rolling his eyes and taking in vast gulps of air. He lived and breathed the moment.

Last year, after three defences, Frampton and McGuigan were in a New York ring after twelve rounds, waiting for confirmation that another world title was coming their way. It was a formality, Frampton had given previously unbeaten Leo Santa Cruz a boxing lesson to take the WBA featherweight title. An Irish man becoming a champion in New York; it’s a modern fairy tale, they write songs about it and sing them in desolate, windswept village pubs in the west of Ireland.

There was a tight loss to Santa Cruz in a rematch this January in Las Vegas. The boys took it well, they are fighting people and now, this weekend, they will both climb back in the ring in Belfast. McGuigan will be taking those long breaths, desperate to let a few punches fly and Frampton will look across at Andres Gutierrez knowing this is the most important fight of his life.

They both need a win before they can move on and only one of them can throw the punches.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks