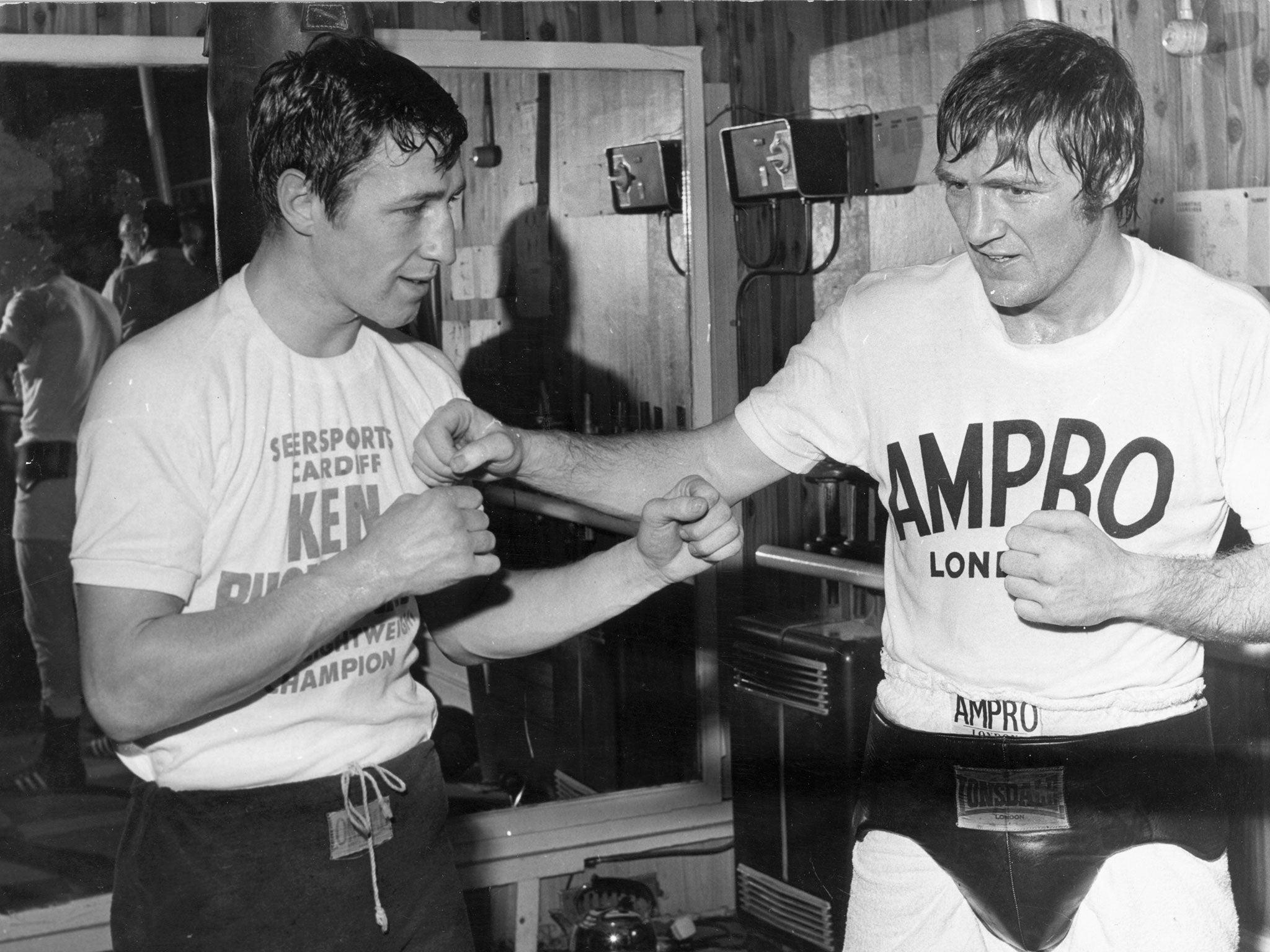

Exotic names and remote locations that British boxers resorted to during the 1970s in pursuit of world titles

Ken Buchanan was Britain's first world champion in the 1970s but those in charge of British boxing refused to acknowledge his success in a very different era for domestic fighters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a time in the last fifty years when world champions had impossibly exotic names and won and lost fights at locations so remote they could have been invented.

On the rare occasion in the Sixties and Seventies when a British boxer was selected by one of the two sanctioning bodies to fight for a world title, he gathered an armada of the faithful and set off on his hopeless mission. The best in British boxing suffered losses in Buenos Aires, Tokyo and Melbourne in short and long fights during decades when every world champion seemed unbeatable.

In January 1970 not one British boxer held a version of the world title and in rings from Caracas to Sendai the seemingly endless list of brilliant fighters traded punches and championships in fights that the finest from Britain’s rings could view only through fantasy goggles. The champions had names that sounded like a cross between a dinner table Sherry and a Peruvian guerrilla leader and the venues for their fights sounded magical. Ruben Olivares, Carlos Monzon, Antonio Cervantes, Guts Ishimatsu and Erbito Salavarria were more like fighters from fiction than men of flesh with wicked left hooks; they seemed like men that could only be reached after an endless railway journey, a night camping on the way with man-eating tribesman, a banquet somewhere of poison fish and finally a ceremonial meeting with a man called Guts or Cervantes. They were champions at the end of the boxing rainbow.

It was at an outpost in this hostile foreign frontier that Ken Buchanan backed his pale body in a crazy afternoon fight under the scorching sun in 1970 to beat Ismael Laguna, which sounds like the outlet of a forgotten river in Central America, in Puerto Rico to become the first British world champion of the decade. A year earlier wee Kenny had quit the moribund fight industry because there was no money and fewer international opportunities; he was only in with Laguna as the supposed loser. It was voted the best fight of 1970 by the American Boxing Writers’ club

Buchanan arrived back in Scotland to be met by just six people. He stood there at arrivals, his face marked and hidden under the brim of a large red sombrero hat and wondered at the snub. “What is the bloody point?” he asked. The men that ran British boxing, refused to acknowledge his win and warned the returning idol that he had been in breach of their rules for accepting the fight.

After the win in the sun, assisted during the minute intervals in the fifteen round fight by a parasol purloined from a ringside guest, Buchanan was transformed into the Tartan lord of the magnificent Madison Square Garden ring, a venue rich in admiration for tiny, frail little battlers with hearts the size of small islands.

In the early Seventies the British boxing business still peered at the world from behind its wall of black, grey and white fights and looked at the wildly successful Buchanan with equal measures of respect, wonderment and resentment as the Scottish fighter conquered boxing lands that seemed to exist at the very edge of the map. In late 1970, in the sunken corridors at the Garden, Ken Buchanan, the lightweight from Edinburgh, shared a dressing room with Muhammad Ali. “He was a nice guy,” Ken said. The pair shadow-boxed side-by-side, each getting ready for their fights in what was then the sport’s greatest arena. Buchanan’s world title win and his defences started the modern British boxing business.

That was all so long ago, so remote from the sport now where 11 British boxers hold a version of the world title and this Saturday in Leicester, Tommy Langford will try and add his name to the list. At the end of 1970, when just two governing bodies sanctioned world title fights compared to the four that are generally recognised today, there were only 15 champions; right now Langford would add his name to a mad scroll of just under 100 men holding a world title. Langford is fighting for the WBO’s interim middleweight title against a man called Avtandil Khurtsidze, who is a foot shorter but starts as the betting favourite. It might lack the exotic allure, the big name, the iconic location, but it will be a good fight and that is something Buchanan would understand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments