From Ivan Drago to Alexander Povetkin and the dark arts in between - the history of Soviet Union boxing

In many ways Rocky IV depicted what the Soviet Union relied on to reach the top of the sport, but somewhere along the way Igor Vysotsky slipped through the net - as Muhammad Ali can testify

Ivan Drago was not the last heavyweight Olympic gold medal winner from the Soviet Union with a history of savagery, secrecy and silence in the boxing business.

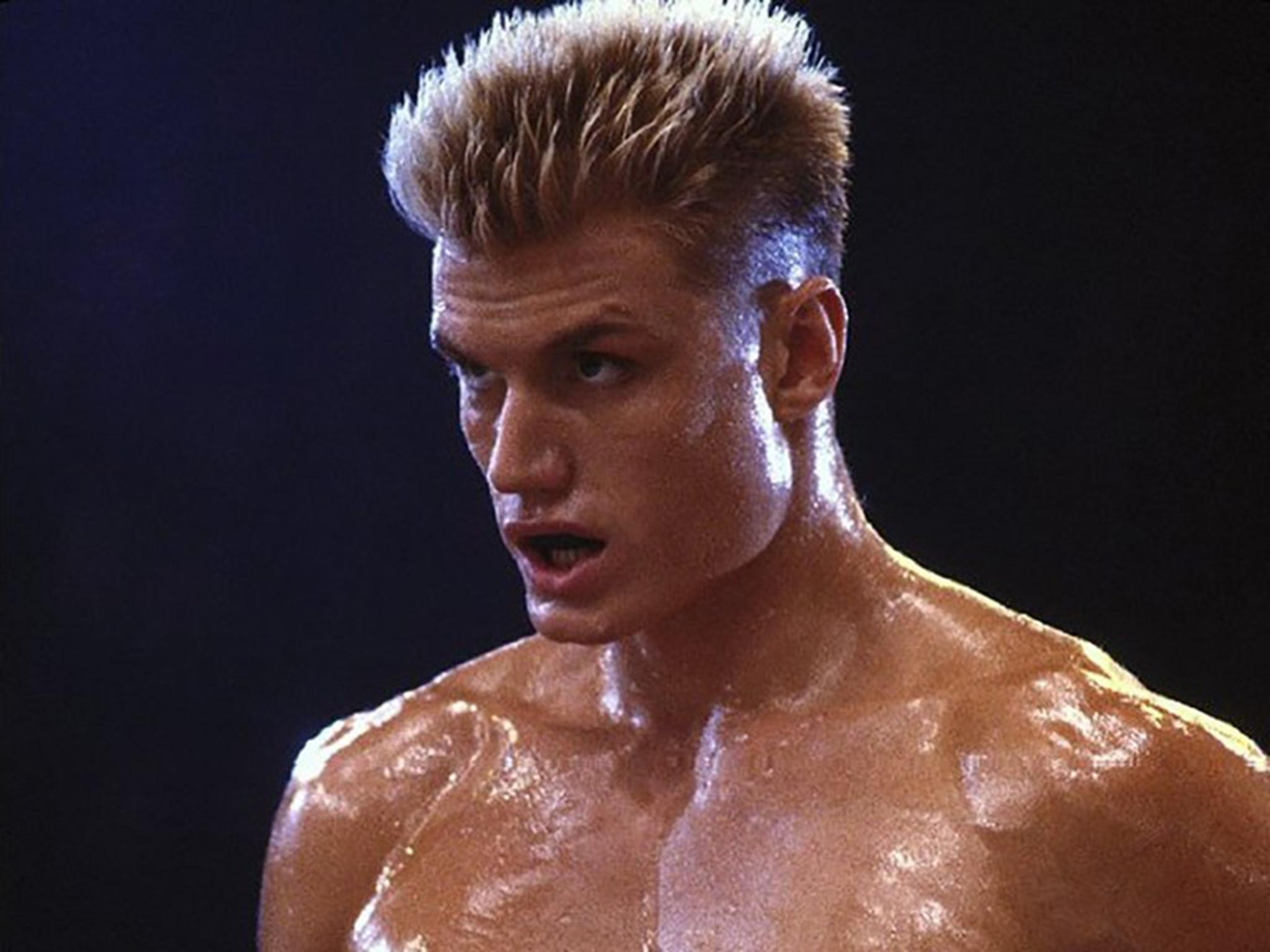

The storyline in Rocky IV is simple: Drago wins Olympic gold by using all of the dubious dark arts that the elite athletes from the old Soviet bloc exploited so infamously for so long. Then, he fights Rocky. Drago, in real life a big softie called Dolph Lundgren, became the first boxer from behind the Iron Curtain to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world in the 1985 movie (Vitali Klitschko was the first real Soviet boxer to fight for the heavyweight championship in 1999). All the Drago stuff is fiction, I know, but still fun, and nobody should ever forget that Sylvester Stallone really does believe he was the heavyweight champion of the world and routinely talks about his fights like they happened.

In 2004 in Athens, Russia’s Alexander Povetkin did win the last Soviet Olympic gold at super-heavyweight and he did become world champion in 2011. Povetkin, like the fictional Drago, has also travelled through the darkest corners of the sport, skirted the very edges of exile with his own drug issues and still remains a serious threat to Anthony Joshua’s jolly mission to become the only man with a belt. The pair will fight in September, a direct result of the WBA, the oldest sanctioning body, insisting on it and also the constant failure of all involved to make a fight between Joshua and the WBC champion Deontay Wilder.

Povetkin has repeatedly proved he can really fight, finish a fight and is still, at 38, a very real contender in a shrinking heavyweight world. Thankfully for Joshua, Povetkin is four inches shorter and about three-stone lighter than Drago. In March of this year Povetkin was on Joshua’s undercard in Cardiff and after he was staggered and fell into the ropes against Liverpool’s David Price, he found a single punch to drop Price and break his nose. Price’s dimensions are impressive; he is two inches taller and 14 pounds heavier than Joshua.

Somewhere between the daftness of Big Ivan and the true tales of Povetkin, there is a Soviet fighter that sounds like fiction in many ways, one of the greatest boxers you have never heard of. Igor Vysotsky was born in a gulag in Magadan, one of Joseph Stalin’s criminal and political prisoner colonies. He never won an Olympic gold, never had a chance at professional glory, but he left a huge legacy with just a few sensational cameos in the boxing ring, fights that remain in all their grainy and tinny splendour on ancient film.

In 1973 in Cuba, Vysotsky easily best Teofilo Stevenson on points; Stevenson had won the first of his three Olympic gold medals in Munich the previous year, stopping all of his opponents. In early 1976 the pair met again and Stevenson took two counts before being knocked out in the third round in Minsk. A few months later the Cubans took two heavyweights to the Montreal Olympics, knowing Vysotsky was due to be there and that Stevenson would not beat him. However, Vysotsky was supposed to have suffered a cut, was not entered in the final draw and that meant the mighty Stevenson won his second Olympic gold medal.

Reading between the lines – often the only way to have any idea what was happening in Soviet sport back then – it is clear that Igor, the Magadan baby, was a handful, not one the selectors’ liked sending on sporting trips overseas. He was obviously a hazard athlete, one of a mysterious group we generally never ever hear about – they were men and women considered too dangerous for travel to the West, a legion of truly unknown sporting ghosts, remembered only by their family and the men that tucked them away in files.

In 1978 Muhammad Ali went on a Peace Mission to Moscow, he was between fights, a bit heavy but he was still Ali. An exhibition was arranged and Ali handled two opponents with ease over two rounds each and then Igor entered the ring, his bright red vest glowing in the film; Ali was topless, paunchy and blowing when the big lump, the forgotten man of Soviet boxing, started to pump away with his textbook jolting jab. Ali had to work to survive, using a life of guile in the ring, his granite chin and for decades Ali remembered the last guy from that so-called exhibition bout. Some say they wore tiny six-ounce gloves and that up close it was brutal on Ali.

Long, long before the mixed list of Soviet bloc heavyweight champions of the world, Oleg Maskaev, Siarhei Liakhovich, Sultan Ibragimov, Ruslan Chagaev, Nikolai Valuev, the Klitschko brothers, Povetkin and even before sweet Ivan Drago was knocked out in round 15 by Rocky, there was Igor, punching for pride, his tiny red gloves a blur as he led Ali on a merry dance one night in Moscow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks