Stargazing in March: The Sun’s fury

Like rubber bands wrapped around our local star, magnetic fields get wound up as the Sun rotates, and – after years of increasing tension – something has to give, writes Nigel Henbest

With the spring equinox this month, we’re feeling the Sun more strongly week by week. But the Sun is hotting up in other ways, too, as its surface suffers more and more severe storms.

The most obvious sign of its malaise was an angry black wound that appeared on the Sun’s shining face last month. The sunspot was 10 times the size of the Earth: so large that it was seen by the Perseverance rover on Mars. And on 22 February, this region erupted in the biggest explosion the Solar System has seen in six years.

The driving force behind the Sun’s fury is magnetism. Like rubber bands wrapped around our local star, magnetic fields get wound up as the Sun rotates, and – after years of increasing tension - something has to give.

Huge loops of magnetic field push up through the solar surface, hindering the flow of heat from deep inside the Sun. These cooler regions appear as dark sunspots. Although it looks black by contrast with its brilliant surroundings, a sunspot seen against a dark sky would actually shine brighter than the full Moon.

The intense magnetism around and above last month’s giant sunspot, catalogued AR3590, kept short-circuiting in solar flares - stupendous flashes of light and energy. The most intense – on 22 February - was rated an X6.3 on the astronomers’ scale, where X is the most powerful kind of flare, and 6.3 is high up in the range.

We expect solar storms to build to a peak sometime in 2024. And what we’ve witnessed so far may be just the prelude. We’ve been lucky that the recent flares haven’t been a serious danger to the Earth, just causing some interference with radio broadcasting.

But magnetic short-circuits on the Sun often shoot a blast of particles in our direction, in an interplanetary broadside called a coronal mass ejection. The most intense solar bombardment in history impacted our planet in 1859. British astronomer Richard Carrington saw an unusually bright solar flare on 1 September, bordering a sunspot 60 per cent larger than AR3590. The next day the Earth was convulsed with magnetic and electrical disturbances as the coronal mass ejection hit our planet’s magnetic field. Current surged through the long-distance wires carrying telegraph messages across the USA, electrocuting operators as they sat at their equipment. A similar impact today would be catastrophic.

But there’s one aesthetic upside to such an event. The solar energy dumped in the Earth’s atmosphere, at its north and south magnetic poles, lights up the skies in spectacular displays of the aurorae – the shimmering green and red curtains of the Northern and Southern Lights. The solar storm of September 1859 was so powerful that aurorae were seen not just in the polar regions, but as near to the equator as Jamaica, where the inhabitants were convinced they were seeing Cuba on fire.

Whatever is in store this summer, the solar activity should abate by the end of the year. The Sun’s powerful magnetism will dwindle as numerous short-circuits sap ifs strength, and sunspots, flare and coronal mass ejections will fade away over the next few years. Eventually, though, activity will build up again as the Sun heads towards the next peak in its 11-year cycle of magnetic activity.

CAUTION: A sunspot the size of AR3590 is visible to the unaided eye, but NEVER look at the Sun directly with your unprotected eyes or – especially – with a telescope or binoculars: it could blind you permanently. For naked-eye observing, use special “eclipse glasses” with dark filters (meeting the ISO 12312-2 safety standard). Or you can attach a sheet of a specialised metallised film across the front of your instrument as a safe filter.

What’s Up

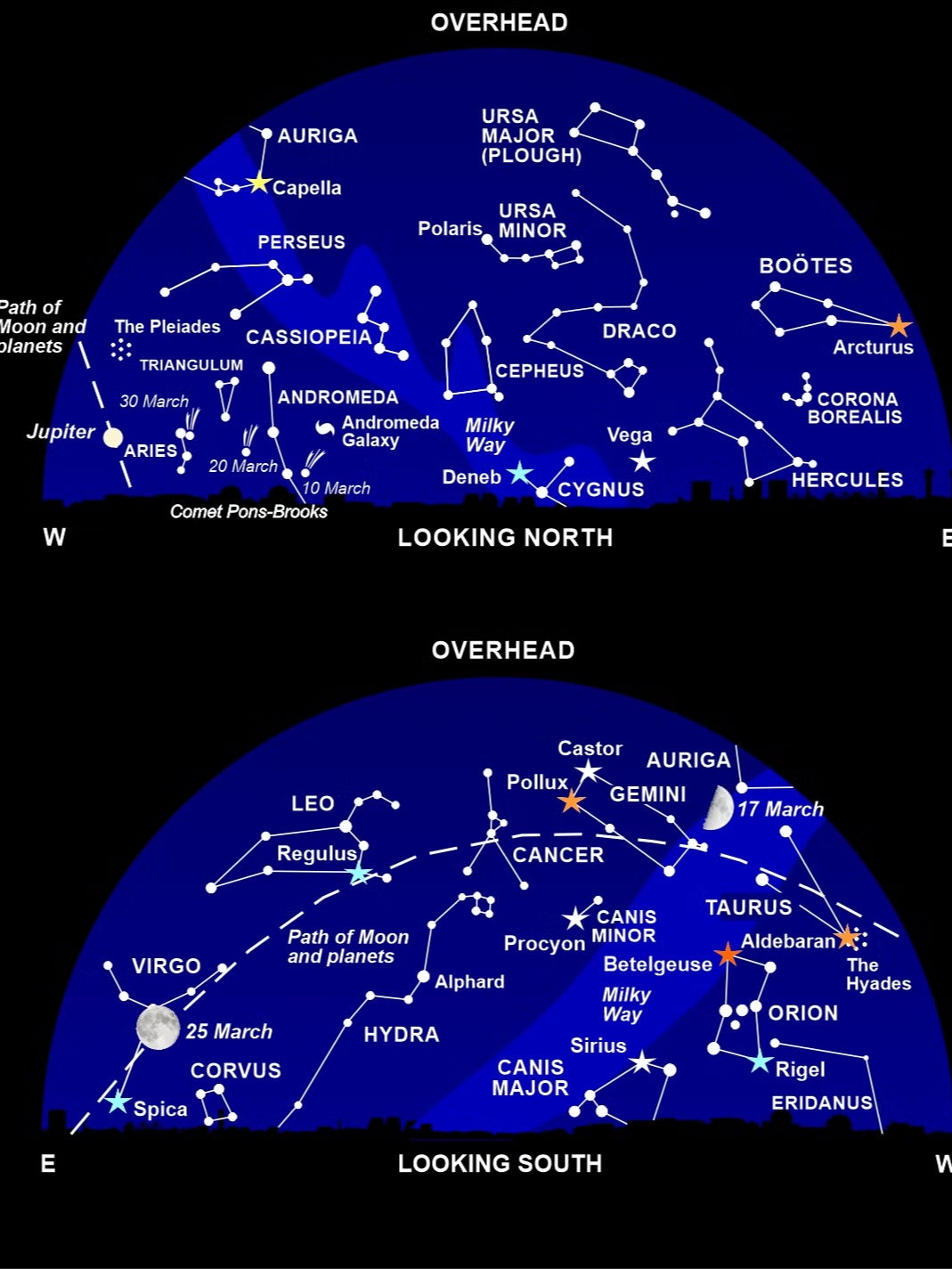

Most of the brighter planets are lost in the Sun’s glare this month, but we have an unusual chance to see the biggest and the smallest planets together in the evening sky.

Mighty Jupiter is the brilliant light over in the west after sunset, shining brighter than any of the stars with a steady cream-coloured light. Around the middle of the month, look low on the horizon to the lower right of Jupiter to spot diminutive Mercury, putting on its best evening show of the year.

As the innermost planet of the Solar System, Mercury never strays far from the Sun in our skies: you’ll always see it against the twilight glow. But with a clear western horizon, you should be able to spot Mercury as an isolated ‘star’ between about 13 and 27 March, around 7 to 8 pm.

In the early morning of 25 March, check out another celestial challenge: see if you can perceive that the Moon is slightly dimmed as it moves into the outer part of the Earth’s shadow, in a penumbral lunar eclipse.

And finally, try to track down the celestial visitor that’s in the news at the moment. Comet Pons-Brooks is travelling through our skies towards its encounter with the Sun next month, and gradually brightening as it goes. With binoculars, you should be able to pick it out in the western sky - about the same altitude as Jupiter, but further to the right, as shown on the chart. The comet suffers occasion outbursts, famously giving it a ‘horned’ appearance, and there’s just a chance it may flare up brightly enough for you to see with your unaided eyes.

Dairy

10 March, 9am: New Moon

13 March: Moon near Jupiter

17 March, 4.11am: First Quarter Moon

18/19 March: Moon near Castor and Pollux

20 March, 3.06am: Spring Equinox

21 March: Moon near Regulus

24 March: Mercury at greatest elongation east

25 March, 7am: Full Moon; penumbral lunar eclipse

26 March: Moon near Spica

31 March, 1am: British Summer Time begins

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks