Stargazing in January: A true epic playing out across the sky

Orion and his entourage represent a palimpsest of human stories that stretch back to the earliest civilisations, writes Nigel Henbest

As the glowing curtains of daylight fade, to reveal the darkened cosmic stage behind, we’re treated this month to a legendary cast of characters. Centre-stage is the familiar figure of Orion, a humanoid shape formed from seven bright stars each around 50,000 times more luminous than our sun.

Orion and his entourage represent a palimpsest of human stories that stretch back to the earliest civilisations. It’s a cosmic drama that unfolds in several distinct acts, spanning not only time but the entire globe.

Act one began under the sable skies of the Australian outback, some 40,000 years ago, when the Aboriginal people saw the bright stars Betelgeuse and Rigel as the prow and stern of a canoe. The three prominent stars we now call Orion’s Belt were three fishermen out to catch their daily meal.

Around 3000 years ago in Babylon, act two opens. Astronomers joined up the dots in the sky to form the basis of the constellations that have come down to us in the West today. To them, the figure we know as Orion was SIPA.ZI.AN.NA - the True Shepherd of Anu (the great god of the sky) - and he presided over a pastoral skyscape. The square of stars we call Pegasus was a field; Cassiopeia represented a horse; while stars in Andromeda and Triangulum were a plough and a stag.

There’s also a bull, inherited from the sky lore of the Elamite civilisation on the shores of the Persian Gulf. That pattern remains to this day as the constellation Taurus. At the time, he was seen as a placid beast, with his back turned to the True Shepherd.

Act three unfolds in nearby Sumer. Ancient Sumerian tales linked our Orion constellation to the great hero Gilgamesh. He was probably a historical king, but fantastical legends soon syncretised around him. In one tale, Ishtar - daughter of the sky-god Anu - fell for Gilgamesh. When he spurned her advances, Ishtar persuaded her father to unleash the fearsome Bull of Heaven...

The resulting epic bullfight is painted in our skies. Reversed from its previous depiction, Taurus is now a fearsome beast facing Gilgamesh (the constellation Orion), with its horns lowered. After an epic struggle, the hero slays the bull by thrusting his sword into its exposed throat.

The Greeks provide us with act four. The humanoid constellation has now metamorphosed into Orion, the most handsome man who ever lived, and the greatest hunter the world has known. On one epic killing spree, Orion boasted that he would destroy all the wildlife on Earth. Appalled, the earth-goddess Gaia sent a scorpion to lethally sting Orion on the heel, while he was focusing on greater prey.

The gods raised both the deceased Orion and the scorpion to the heavens – but on opposite sides of the sky. Orion is visible in the winter, while the stars of Scorpius (the constellation representing the fatal scorpion) appear in the summer, so the two are never above the horizon at the same time.

The Greeks dressed the stage with suitable companions for Orion: his two hunting dogs (Canis Major and Canis Minor), along with a hare (Lepus) for him to pursue in the heavens.

By way of digression, act five takes us to China, where astronomers called Orion Shen Xiu, meaning "the three stars," and identified the trio of stars in Orion’s belt as the lucky goddesses of fortune, prosperity and longevity. These stars line up vertically when Orion rises at the Chinese New Year.

Under the clear desert skies of the Middle East, Arab astronomers unveiled act six. They saw the constellation shape not as a shepherd, a hero or a hunter – but as a female giant, al-Jawza. She had two sisters, and was engaged to be married. But something terrible happened on her wedding night (the myths are silent on what occurred), and in the morning she was found dead. We see her sisters as the bright stars Sirius and Procyon, while her husband – the star Canopus - fled down over the horizon to the south.

Though we don’t recognise al-Jawza as a constellation these days, her ghost lives on. The names of Orion’s stars are derived from the Arabic for various parts of her body and clothing: Rigel, for instance, means "the foot." The famous star Betelgeuse gets its name (via a bit of mis-transliteration) from the Arabic yad al-jawza, "the hand of the female giant."

The denouement of these acts is the great tableau of constellations that we see taking a curtain call in the southern skies this month.

But there are a couple of encores, too. In 1627, a German astronomer called Julius Schiller redrew the ‘pagan’ constellations as Biblical figures. Orion was reincarnated as a carpenter surrounded by his tools: St Joseph, husband to the Virgin Mary.

And the final turn came in 1944, when the British writer A P Herbert decided it would be easier for servicemen in the Second World War to navigate if the constellations and stars had more familiar names. Orion was transmuted once more into the Sailor, with its freshly minted star-names including Drake (Rigel) and Nelson (Betelgeuse).

What’s Up

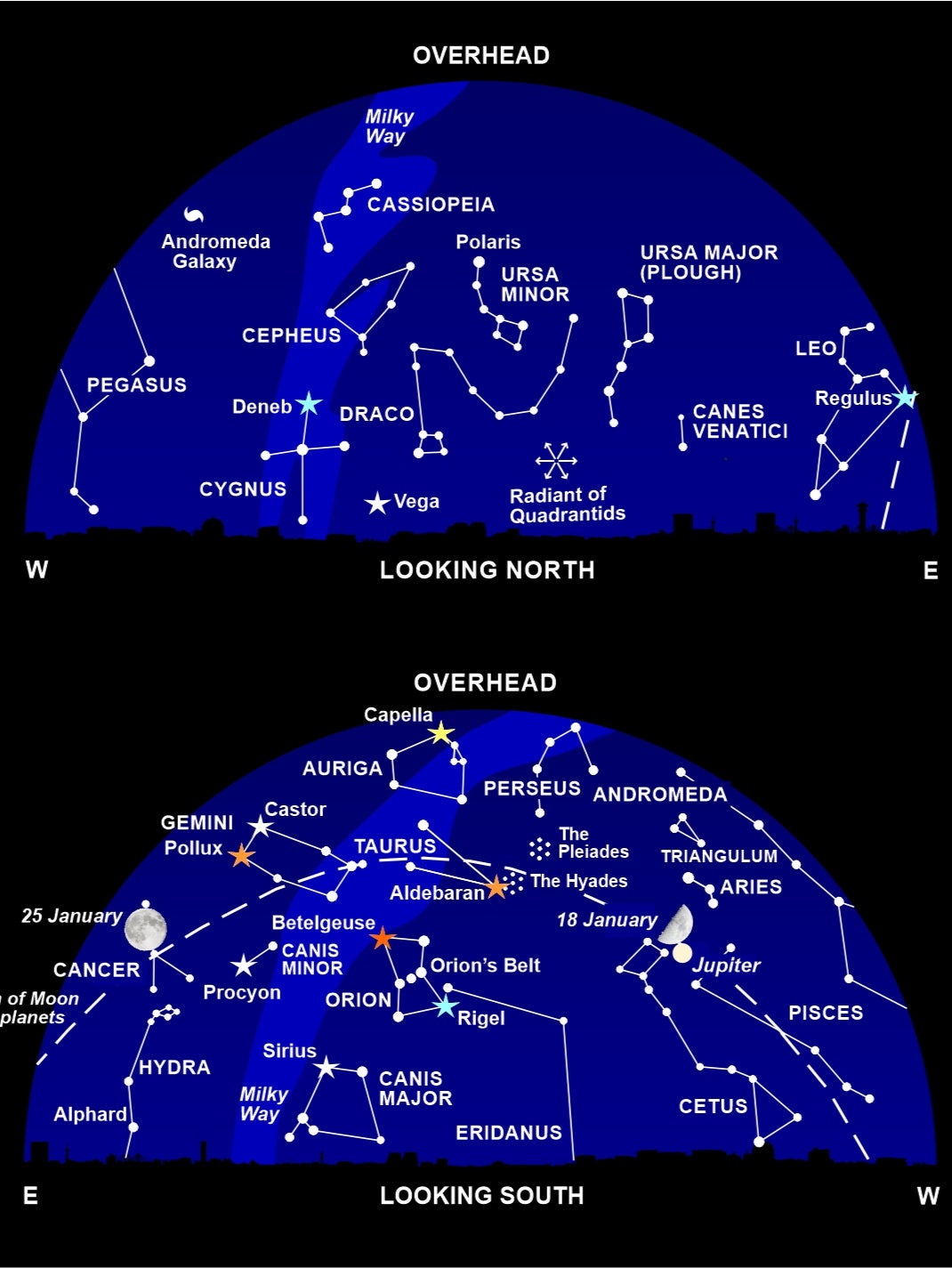

Jupiter is brilliant in the evening sky to the south-east. and sets around 1.30am. The moon passes just above the giant planet on 18 January. Well to the lower right of Jupiter, and 25 times fainter, you can catch the Solar System’s second gas giant planet, Saturn, until it sets about 8pm. On 14 January, the crescent Moon lies to the left of Saturn.

To the south, we have a wonderful view of the brilliant stars of winter. Centre-stage is Orion with red giant Betelgeuse marking one of his shoulders and blue-white Rigel at the lower edge of his tunic. Three bright stars depict Orion’s belt: follow them downwards to find Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, and upwards to locate Aldebaran, the orange-red eye of Taurus (the bull) and – further on – the Pleiades, a lovely star cluster popularly known as the Seven Sisters.

Forming a giant arc between Sirius and Aldebaran are four bright stars. Procyon is the leading light of Canis Minor (the little dog); Pollux and Castor are the twin stars of Gemini; while Capella crowns the constellation of Auriga (the charioteer).

If you’re up before dawn, enjoy the sight of glorious Venus as the Morning Star, over in the south-east. The crescent moon lies near Venus on the morning of 8 January. Scrutinise the horizon to the lower left of Venus around the middle of January and you may spot elusive Mercury, which never strays far from the Sun. There’s a great chance of locating Mercury on the morning of 9 January: take a line from Venus to the thin crescent Moon and extend it an equal distance to the left, and the “star” you’ll find there is the innermost planet.

Dairy

8 January, early hours: Moon near Venus

9 January, early hours: Moon between Venus and Mercury

11 January 11.57am: New Moon

12 January: Mercury at greatest elongation west

14 January: Moon near Saturn

18 January, 3.53am: First Quarter Moon near Jupiter

20 January: Moon near the Pleiades

24 January: Moon near Castor and Pollux

25 January, 5.54pm: Full Moon

27 January: Moon near Regulus

31 January: Moon near Spica

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments