Stargazing in April: A total eclipse

I certainly wasn’t prepared for the emotional impact when I saw my first total eclipse, writes Nigel Henbest

Fifty-second day: fog until next dawn. Three flames ate the Sun, and big stars were seen.” So runs the oldest written account in the history of astronomy, dating back to 5 June 1302 BC.

To anyone who’s witnessed of a total eclipse of the Sun, the description strikes a chord even today. The “three flames” are streamers in the Sun’s atmosphere, the corona, reaching out from around Moon’s silhouette. And when the sky goes dark, we suddenly get to see ‘big stars’ – in this case, Sirius and the planets Saturn and Venus.

The eclipse was such an incredible sight that this eyewitness account echoes down to us over three millennia. And even in today’s world of constant visual stimulation, a total solar eclipse is something so unique that I guarantee it’s a sight that you will never forget.

I certainly wasn’t prepared for the emotional impact when I saw my first total eclipse, from the shores of Bangka Island in Indonesia, back in 1988. Sure, I knew scientifically what would occur, and I’d briefed my group of eclipse-tourists the previous day.

What I wasn’t expecting was the visceral impact. The familiar golden face of the Sun, familiar to us every day of our lives, was replaced by something totally weird and alien. To me, the eclipsed Sun was a dragon, its black maw fringed by the glowing tendrils that surround the face of a Chinese dragon. To my surprise, I felt fear.

In many traditions around the world, a solar eclipse was literally seen as some kind of cosmic monster devouring the Sun. The ancient Greeks, intent on rationalising the universe, realised that the culprit was the Moon, moving in front the Sun’s face. In 585 BC, the pioneering scientist Thales, living in Miletus in what is now Turkey, first predicted a solar eclipse – though his work didn’t make it as far as the neighbouring kingdoms of the Medes and the Lydians, whose armies were in the midst of a bloody battle. Both sides were so awestruck that they laid down their arms and immediately signed a peace treaty that ended a six-year war.

Total solar eclipses actually aren’t all that rare. There’s one every couple of years or so. But they are only visible from the narrow path across the globe that’s traced out by the Moon’s shadow. At any place on Earth, you’d have to wait 375 years after one total eclipse to view the next. That’s an average: from some places on Earth, you may not see an eclipse in more than 3,000 years, while one region of the desert of Western Australia will be treated to two total eclipses only 18 months apart, on 13 July 2037 and 26 December 2038.

Coming up this month, on 8 April, a total solar eclipse will wow people in North America. The eclipse path makes landfall at Mazatlan in Mexico, and the maximum length of totality – 4 minutes 18 seconds – will be seen from Nazas, now dubbed ‘eclipse city.’ Sweeping into Texas, the Moon’s shadow passes over Dallas, before crossing into Arkansas and Illinois, where the town of Carbondale will experience its second total eclipse in seven years, having been on the path of the 21 August 2017 total eclipse.

The 2024 experience continues in Indianapolis (Indiana), Cleveland (Ohio), Buffalo and Niagara Falls (New York), and Montreal (Quebec). With so many major cities plunged into darkness, this will be one of the most-observed eclipses in history, with an estimate 44 million people living in the eclipse path – not to mention the millions more tourists expected to flock there.

The Sun is near the maximum of its 11-year cycle of magnetic activity [link to last month’s column], and that means its corona should be particularly spectacular this time. Based on my more recent experiences with the eclipsed Sun, I will still be awed by the sight – but now it’s not a fearsome dragon I respond to, but a beautiful flower with a dark heart and pale luminous petals.

What’s Up

Giant planet Jupiter has been a show-stopper in the evening sky since last autumn, but this is your last chance to view the mega-world before it disappears behind the Sun.

Even a pair of binoculars, held steady, will show you its four largest moons – their chief, Ganymede, is even larger than the planet Mercury. And a small telescope reveals the bands of dark and bright clouds wrapped around the gaseous planet. The crescent Moon forms a lovely duo with Jupiter on 10 April.

And use Jupiter as a guide to finding the interplanetary tramp that’s been making waves recently. Comet Pons-Brooks has been gradually brightening as it’s approaching the Sun, and you can find it in binoculars below Jupiter around 10 April to 15 April.

A few months ago, the comet was flaring up every few weeks, and we had hoped that by now Pons-Brooks might be suffering outbursts that would propel it to naked-eye visibility. But the comet has calmed down, and it’s likely we’ll only be able to see it in binoculars or a telescope, especially as it’s now sinking down into the evening twilight as it heads for its closest point to the Sun on 21 April.

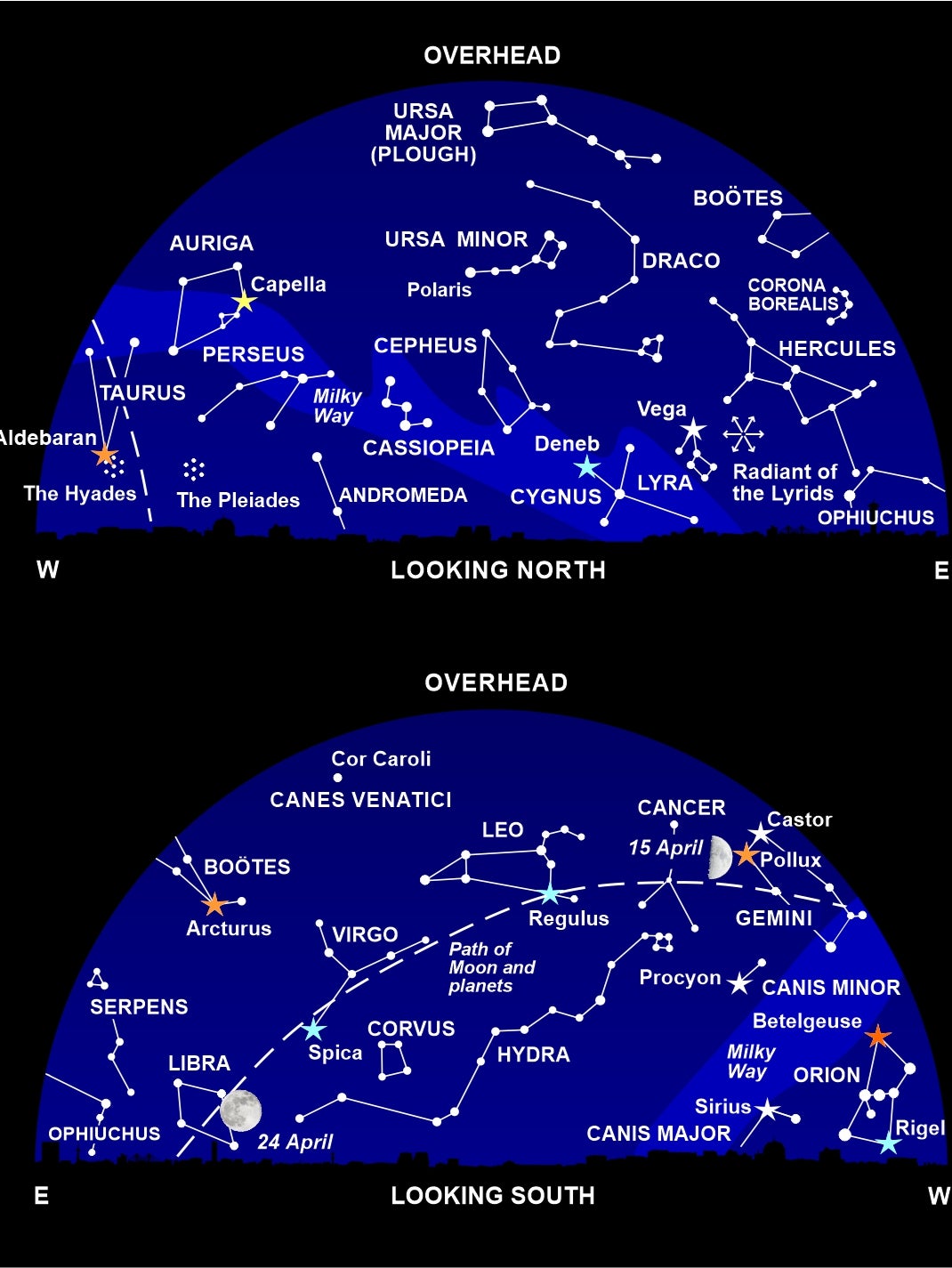

The gaudy winter constellations of Orion, Gemini Auriga and the two celestial hounds – Canis Major and Canis Minor – are now sinking down into the west. Their places are taken, in the southern sky, by the crouching feline form of Leo (the Lion), with the Y-shape of Virgo (the Virgin) to its lower left. The bright star to the upper left is Arcturus, the leading light in Boötes (the Herdsman)

Look out for a shower of shooting stars on the night of 22/23 April, though it’s not a good year for observing the Lyrids - incandescent fragments shed by Comet Thatcher – because bright moonlight will drown out all but the brightest meteors.

Dairy

8 April 7.20pm: New Moon; total solar eclipse

10 April: Moon near Jupiter

13 April: Comet Pons-Brooks below Jupiter

15 April, 2.53pm: First Quarter Moon near Castor and Pollu

20 March, 3.06am: Spring Equinox

18 April: Moon near Regulus

21 April: Comet Pons-Brooks at perihelion

22 April: Moon near Spica; maximum of Lyrid meteor shower

24 April, 0.49am: Full Moon

26 April: Moon near Antares

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks