Stargazing May: Time to spot the Great Red Spot as Jupiter comes out to play

Now's the best time to look at the gas giant, its biggest moons and its Great Red Spot

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By Jove! Despite competition from Venus, Jupiter is lording it over the heavens this month. On 9 May, the giant planet is at “opposition” – opposite the Sun in the sky, at its brightest, and closest to the Earth. “Close” is a relative term: Jupiter will be 658 million km away!

But it’s time to get out the binoculars or small telescope. The first thing you’ll notice is that Jupiter isn’t round; it’s flattened like a tangerine. Secondly, it’s stripey. Also, you’ll spot some of Jupiter’s biggest moons: four, if you’re lucky. They’re called the Galilean moons, because Galileo observed them in 1610; but credit should go to German astronomer Simon Marius, who spotted them before Galileo, and named them, too.

If you have brilliant eyesight, they’re visible to the unaided eye. That’s because they’re biggies – Ganymede is larger than the planet Mercury. The first time we discovered this was at an evening class we were running. A 78-year-old lady asked what the “little dots” were around the planet. We asked her to draw them; checked the positions with a telescope – and she was right.

What a motley crowd these moons are. Ganymede and Callisto are heavily cratered, as a result of asteroid impacts. Io is alive with active volcanoes. Enigmatic Europa is as smooth as a billiard ball. This icy moon may harbour a warm ocean below its surface, where astronomers suspect that primitive life could exist.

These four moons are just the tip of the iceberg. Jupiter controls at least 69 natural satellites (remember this for the next pub quiz – everyone gets it wrong!). The whole Jupiter environment is a mini-Solar System in itself.

That’s because Jupiter is so enormous. It weighs in at more than more than 300 times the mass of our planet – so its gravity is awesome – and it could swallow 1,300 Earths. And Jupiter couldn’t be more unlike our world. Along with its neighbours Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, Jupiter has no solid surface. It’s a “gas giant”, made of gases it snatched from the early nebula that created the Sun.

In fact – had Jupiter been only 75 times more massive – we would have two suns in our Solar System. Jupiter’s core temperature is an incandescent 35,000C. But even that’s not up to the 10 million Celsius you need if you’re going to create a star, and trigger the nuclear fusion reactions that drive them.

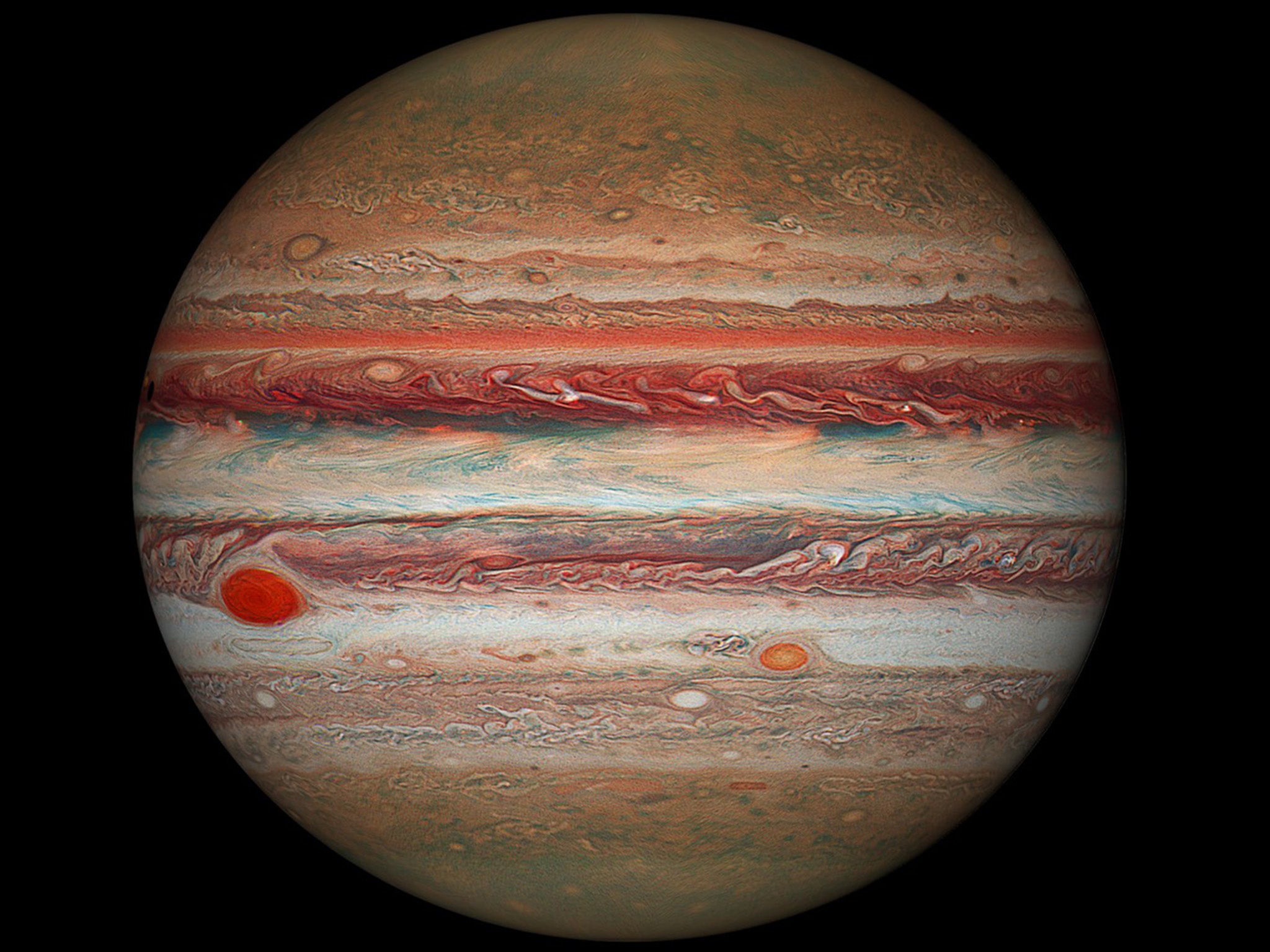

Nevertheless, Jupiter is remarkably frisky. For all its bulk, it’s the fastest-spinning planet in the Solar System – its day is just 9 hours and 55 minutes long (which makes it tangerine-shaped). This draws the gaseous clouds of the planet (mostly made of ammonia and methane) into long streaks of ochre and white.

And there’s plenty of weather in those clouds, which you can observe with a medium-sized telescope. Spots, streaks, sudden outbreaks of storms; it’s like the Earth’s weather, but writ large. Spacecraft have picked up violent flashes of lightning in the planet’s atmosphere.

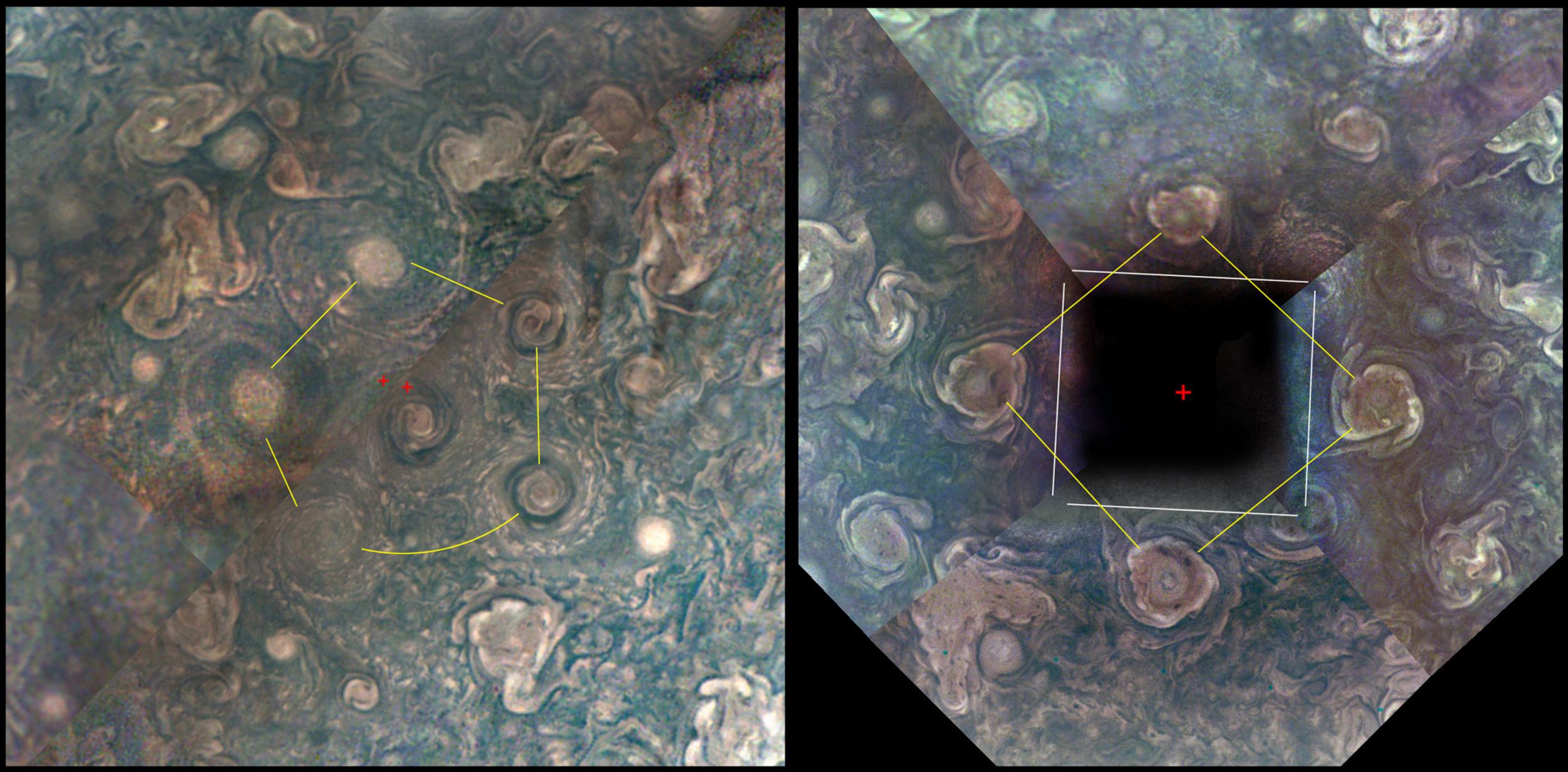

Jupiter has been visited by several (unmanned) spaceprobes, and one – Nasa’s Juno – is currently in orbit. It has discovered some fascinating weather patterns at the planet’s north and south poles: each is surrounded a set of giant cyclones, forming a polygon around the pole itself. Eight cyclones form a neat octagon around the north pole; while five storm systems around the south pole trace out a slightly wonky pentagon. The cyclones are thousands of kilometres across, and boast winds roaring at speeds of up to 350kmh. The storms and the polygonal shapes are making scientists scratch their heads...

Juno has also been monitoring a much-loved feature of Jupiter’s atmosphere. The Great Red Spot has possibly been a feature of the giant planet since it was discovered by Giovanni Cassini in 1665 – but it may be on its way out.

Once three times the size of Earth, this high-altitude anticyclone (coloured red by sunlight) is shrinking. It’s now about the same size as our planet. Worried scientists think that it might disappear altogether, but they’re not sure when. Bets range from 20 to 70 years.

So – beg, borrow or steal a telescope to savour your view of the Great Red Spot before it vanishes!

What’s up?

Despite the weather recently, you can’t have missed the brilliant evening star, blazing in the west after dark. It’s the planet Venus, shining more brilliantly than any star, as its cloudy atmosphere reflects the Sun’s light. Look out for a lovely sight after sunset on 17 and 18 May, when the crescent Moon hangs close to Venus in the twilight.

Over the other side of the sky, rising in the southeast, we have another dazzling planet. As we described above, giant Jupiter is closest to the Earth this month and – like Venus – outshining all the stars.

To the lower left of Jupiter, the red star Antares hugs the horizon. To its right – high in the southern sky – you’ll find the bright stars Arcturus, Spica and Regulus. Along the southern horizon sprawls one of our favourite constellations. Though it boasts no brilliant stars, Hydra (the Water Snake) has the accolade of being the longest and the largest of all the constellations – and probably one of the oldest. The constellation was probably created around 2800BC, when this line of stars marked out the equator of the sky. Its brightest star, Alphard, appropriately means “the lonely one.”

Stay up after midnight, and Saturn appears in the southeast, followed a couple of hours later by Mars. Before dawn on the 6 May, you’ll be in for the added treat of some lovely shooting stars: the Eta Aquarid meteor shower consists of debris from Halley’s Comet burning up in the atmosphere above our heads.

Diary

5 May, morning: Moon near Saturn

6 May, morning: maximum of Eta Aquarid meteor shower

8 May, 3.09am: Moon at Last Quarter

9 May: Jupiter at opposition

15 May, 12.48pm: New Moon

17 May: Crescent Moon near Venus

18 May: Crescent Moon near Venus

21 May: Moon very close to Regulus

22 May, 4.49am: Moon at First Quarter

25 May: Moon near Spica

27 May: Moon near Jupiter

29 May, 3.20pm: Full Moon, near Antares

31 May: Moon very close to Saturn

For the low-down on all that’s up in the sky this year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s latest book ‘Philip’s 2018 Stargazing’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments