Stargazing for November 2017: Lights fantastic

In this month’s stargazing column, Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest examine the best way to see the Northern Lights – and get set for some very watery constellations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Have you booked your trip to see one of the sky’s most fantastic light shows? Do it soon, because the fireworks might start to fizzle out a bit.

The Northern and Southern Lights – the aurora borealis and the aurora australis – are the coolest sky sights you can see. The heavens glow with glorious swirling curtains of changing colours, and the dark skies are pierced with dramatic rays. It’s no wonder that cruise ships and planes ferry tourists in their thousands towards Earth’s poles to witness this incredible celestial phenomenon.

Aberdeen, in the north of Scotland, has a nickname for the many aurorae visible there each year. They’re affectionately known as "The Merrie Dancers". A Scottish former Concorde pilot we met thought that the glows were due to sunlight reflected off the poles.

Close: but not close enough. But he got the culprit right – it is the sun. Roughly every 11 years or so, it gets into a bit of bother with its magnetic activity... Our normally quiescent local star hurls fast-moving electrons and protons into the solar system. Being electrically charged, these rush towards the Earth’s magnetic poles, lighting up the sky like gas in a neon tube.

We see aurorae when the sun has a magnetic storm. Their glorious colours come from the elements in the atmosphere that are being energised by the sun’s particles: high-altitude oxygen (320km and up) glows red; medium-level oxygen gives the aurora its characteristic green colour; while hyped-up nitrogen provides the blue. "Unexcited" nitrogen emits a red-purple glow,

Not close to a pole? No worries. If the sun has a particularly violent magnetic storm, aurorae can be seen well outside the normal polar limits. In the northern hemisphere, we once saw an aurora near Oxford; they have even been reported in the south of France. South of the equator, aurorae are common in New Zealand, and as far from the south pole as Tasmania and South America.

Don’t be too disappointed if your aurora tour doesn’t come up with the goods. Now isn’t the best time to see the cosmic fireworks. The sun usually works its magic when it's near, or just after maximum in its cycle of solar activity. However, it’s close to minimum at the moment. So your psychedelic stellar experience might not be as great as the brochures tell you.

But you can never tell. Our local star is notoriously unpredictable with its magnetic hiccups. We have pals on the Isle of Skye who keep us updated on aurora sightings every week; and it seems that the sun still has a lot going for it.

And if your light show doesn’t deliver, there will still be some sensational dark night skies to gaze upon. Just take a good star map (see below for plug of our latest Stargazing book), plus a good pair of binoculars – and prepare to be overwhelmed by the experience!

What’s Up?

At first sight, the early evening skies look a tad boring this month, enlivened only by Saturn low on the western horizon, joined at the end of November by Mercury.

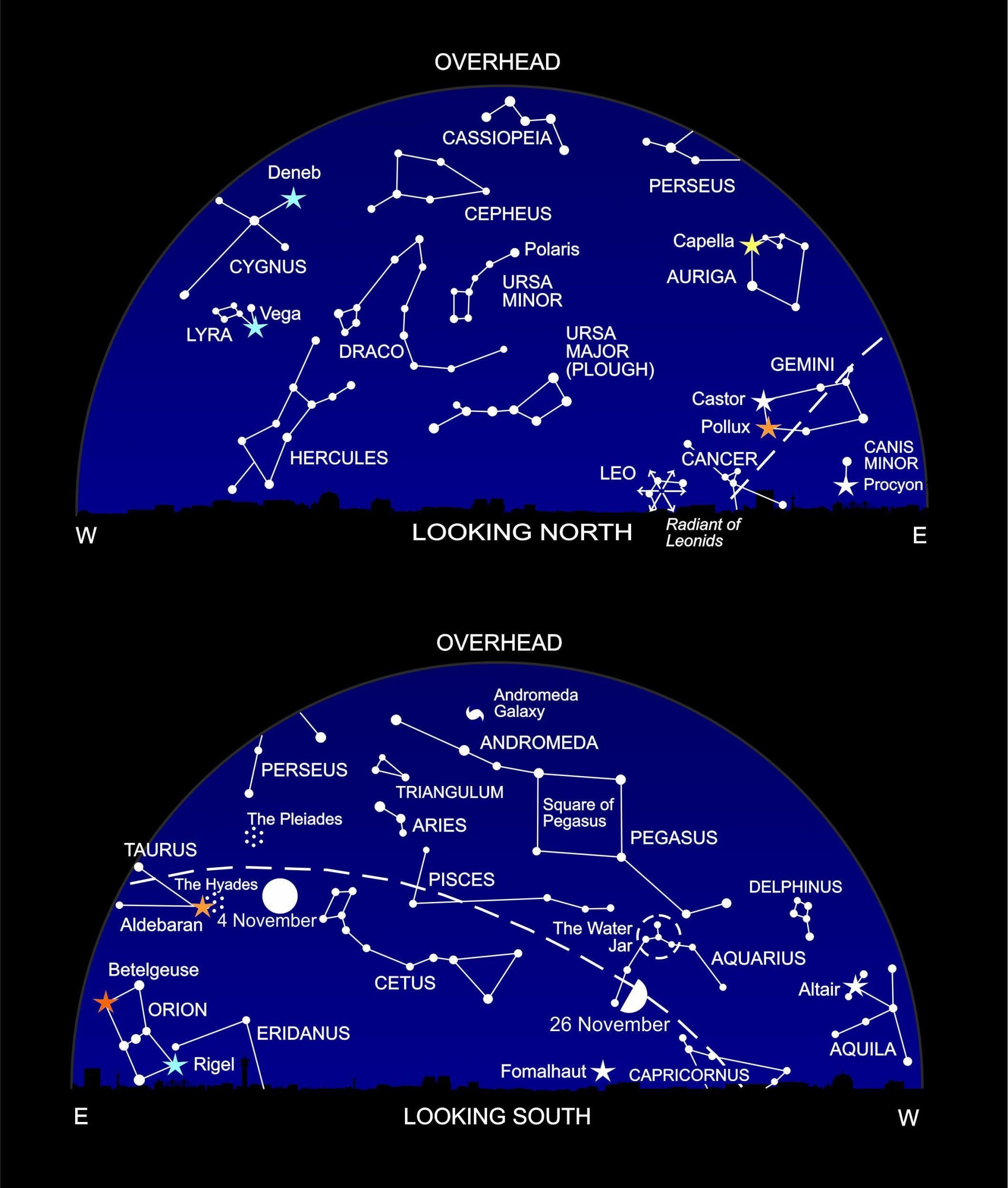

But ancient astronomers painted an incredible tableau of mythical derring-do on the faint autumn stars. Look towards the south: can you spot a distinct Mercedes-Benz symbol in the sky? We’ve picked it out on the map with its traditional name, the Water Jar. In ancient legend, this was a huge jug being carried by Aquarius, the Water Bearer. Water pouring from the jar is represented by streams of stars that head downwards towards one of our favourite stars, Fomalhaut - meaning “the mouth of the fish”.

To the right of Aquarius you’ll find two more watery constellations. A small but perfectly formed diamond of stars depicts Delphinus, the leaping dolphin. Below it, a large triangle of stars representing Capricornus, a strange mythical beast with a goat’s head and body attached to a fish’s tail. Though they are faint, Aquarius and Capricornus are among the oldest constellations we have: they were - for some reason - immensely important to Sumerian astronomers more than 3,000 years ago.

To the left of Aquarius lies another marine beast, Cetus the Whale. He was part of a soap opera that the Greeks later staged in the sky. Cetus was despatched to devour the chained princess Andromeda, who appears in the sky as a line of stars almost overhead, along with her parents Cassiopeia and Cepheus whom you’ll find in the northern sky. In the nick of time, down swooped the hero Perseus (high in the east) who decapitated Cetus and, of course, wed Andromeda.

Meanwhile, take a look at the Moon on Fireworks Night, 5/6 November - preferably with binoculars - and you’ll see it moving in front of the Hyades star cluster; in the early hours of the morning, it hides the bright star Aldebaran.

If you’re a lark, check out the planets rising in the southeast just before the sun. Brilliant Venus is unmistakeable, with fainter Mars to its upper right. On the morning of 13 November, the second brightest planet, Jupiter, passes very close to Venus and then surges up towards Mars.

We can’t leave November without talking about the Leonid meteor shower: in the past they’ve been a real humdinger, but we’re not expecting anything remarkable this year. Hang on in for the amazing Geminid shooting stars next month!

Diary

4 November, 5.23am Full Moon

5/6 November Moon occults the Hyades & Aldebaran

10 November, 8.36pm Moon at Last Quarter

12/13 November Venus-Jupiter conjunction

16 November Saturn’s rings widest open

16-18 November Maximum of Leonid meteor shower

18 November, 11.42am New Moon

23 November Mercury at greatest eastern elongation

26 November, 5.03pm Moon at First Quarter

For a preview of all that’s up in the sky next year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s latest book: ’Philip’s 2018 Stargazing Month-by-Month Guide to the Night Sky, Britain & Ireland’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments