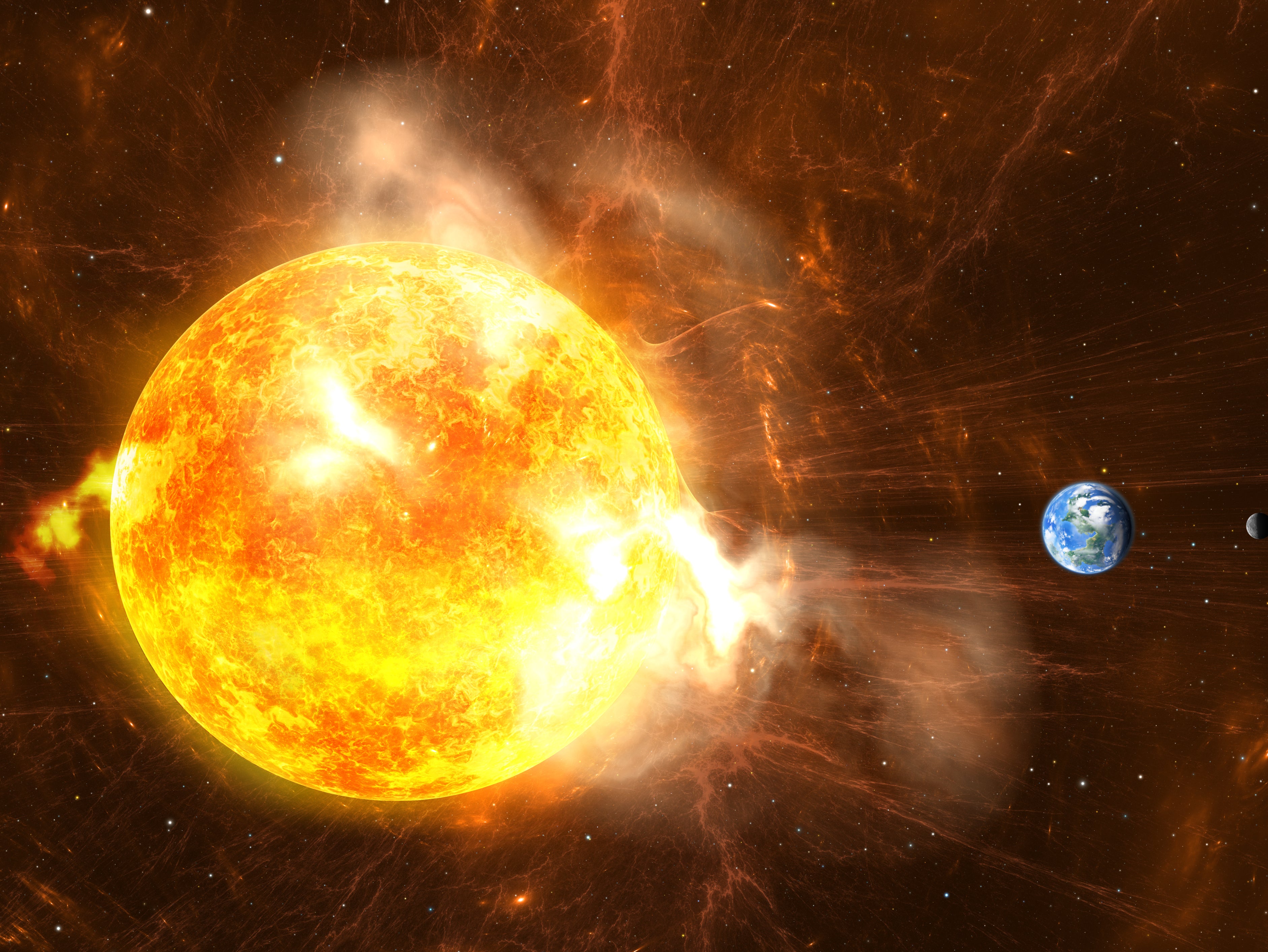

Solar storms are causing satellites to drop from their orbits

Some satellites are dropping over two kilometres per year, and smaller crafts are at a greater risk

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists believe that solar weather could be causing satellites to drop out of their orbits.

Over the past year, the European Space Agency’s Swarm constellation – which measures magnetic fields around Earth – started dropping in the atmosphere ten times faster than before.

"In the last five, six years, the satellites were sinking about two and a half kilometers [1.5 miles] a year," Anja Stromme, ESA’s Swarm mission manager, told Space.com.

"But since December last year, they have been virtually diving. The sink rate between December and April has been 20 kilometers [12 miles] per year."

It’s thought that the new solar cycle – which started concurrently with these phenomena – could be responsible. More solar wind activity, as well as sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections, are being generated at an increasing rate.

"There is a lot of complex physics that we still don’t fully understand going on in the upper layers of the atmosphere where it interacts with the solar wind," Dr Stromme said. "We know that this interaction causes an upwelling of the atmosphere. That means that the denser air shifts upwards to higher altitudes."

The denser air creates more drag for satellites, akin to “running with the wind against you," Dr Stromme said. "It’s harder, it’s drag — so it slows the satellites down, and when they slow down, they sink."

The satellites sunk so dramatically that in May, operators had to raise the altitudes using their on-board propulsion. If satellites drop too low, it is possible that agencies could lose them completely.

Every spacecraft 250 miles from Earth is likely to have problems, Dr Stromme predicts, including the International Space Station. Moreover, small, low-power satellites known as CubeSats have been sent into space at an increasing rate, and these craft are notably vulnerable.

"Many of these [new satellites] don’t have propulsion systems," Dr Stromme said. "They don’t have ways to get up. That basically means that they will have a shorter lifetime in orbit. They will reenter sooner than they would during the solar minimum."

Fortunately, one benefit of the increase in solar activity is that it can help clean up space debris, making detritus orbiting Earth descend and disintergrate in the atmosphere.

There are approximately 228 million pieces of space debris around the globe, that risk keeping us trapped on the planet, but experts say governments have not taken nearly enough action to deal with it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments