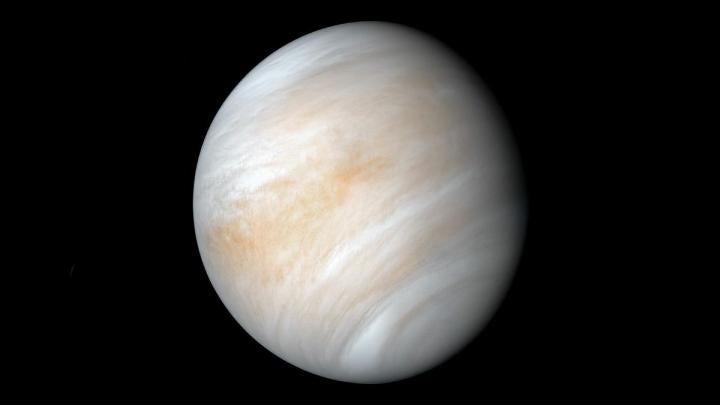

Scientists finally answer mysteries about Venus, including how long exactly its day lasts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have finally answered some of the central mysteries of Venus, our closest neighbour.

The new research helps establish fundamental facts about the planet, including just how long a day lasts there.

As with many of the most basic questions about Venus, that has remained largely mysterious. But now scientists say they have established how long it takes for the world to spin all the way around, how tilted it is, and how big its core is.

“Venus is our sister planet, and yet these fundamental properties have remained unknown,” said Jean-Luc Margot, a UCLA professor of Earth, planetary and space sciences who led the research.

Each day lasts for 243.0226 Earth days, on average, or roughly two-thirds of our own years, the researchers established.

They also found that is tipped to one side by 2.6392 – positively straight, compared with the 23 degrees of our own Earth.

With those measurements, researchers were also able to get a measure of its core. It is about 3,500 kilometres across – roughly the same as our own – but researchers are unable to say for sure whether it is liquid or solid.

As well as helping shed light on our neighbour, the findings will be practically useful for any trips to the surface, since without precise information on how the planet moves, engineers will find it difficult to pinpoint any landing. “That probably explains why previous estimates didn’t agree with one another,” said Professor Margot.

The research saw scientists bounce radar off the surface of Venus over a period of 15 years. The new findings are published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The researchers shone radio waves from an antenna in a California desert onto Venus, 21 times over a period between 2006 and 2010. They were then able to study how they bounced off the surface and came back to Earth, using them to understand how the planet moves.

“We use Venus as a giant disco ball,” said Margot, with the radio dish acting like a flashlight and the planet’s landscape like millions of tiny reflectors. “We illuminate it with an extremely powerful flashlight -- about 100,000 times brighter than your typical flashlight. And if we track the reflections from the disco ball, we can infer properties about the spin [state].”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments