Reach for the stars: will space elevators one day win the ‘green space race’ ?

Catapults, nanotubes and even magnets – Anthony Cuthbertson looks at the dream of a carbon neutral rocket launch and whether any of these methods will ever be able to get us into orbit

On a cool Florida evening in February, with several alligators floating nearby, a rocket took off from Cape Canaveral, sending a satellite into space. It was the second SpaceX rocket to launch that day – one of around 100 that the company will launch in 2023 – and would have been entirely unremarkable if not for the thousands of trees that had been planted prior to lift off.

These trees, and other carbon offsetting initiatives, made the Inmarsat-6 F2 mission the world’s first “carbon neutral rocket launch”. It marked a major milestone for a notoriously polluting industry, however a number of startups are now attempting to go even further by developing launch systems that negate the need for fossil fuels altogether.

Concepts include catapults, magnets, guns and even space elevators, which could deliver payloads into space using electricity alone.

Using electricity from renewable energy sources like solar and wind would make launches environmentally sustainable, while also bypassing criticism that carbon-offsetting does not address the core issue of reducing CO2 emissions at the source.

Zero emission launches would not only make the planet greener, they could also vastly reduce the cost of getting to space. So what are these new technologies, and how close are we to actually realising them?

Space catapult

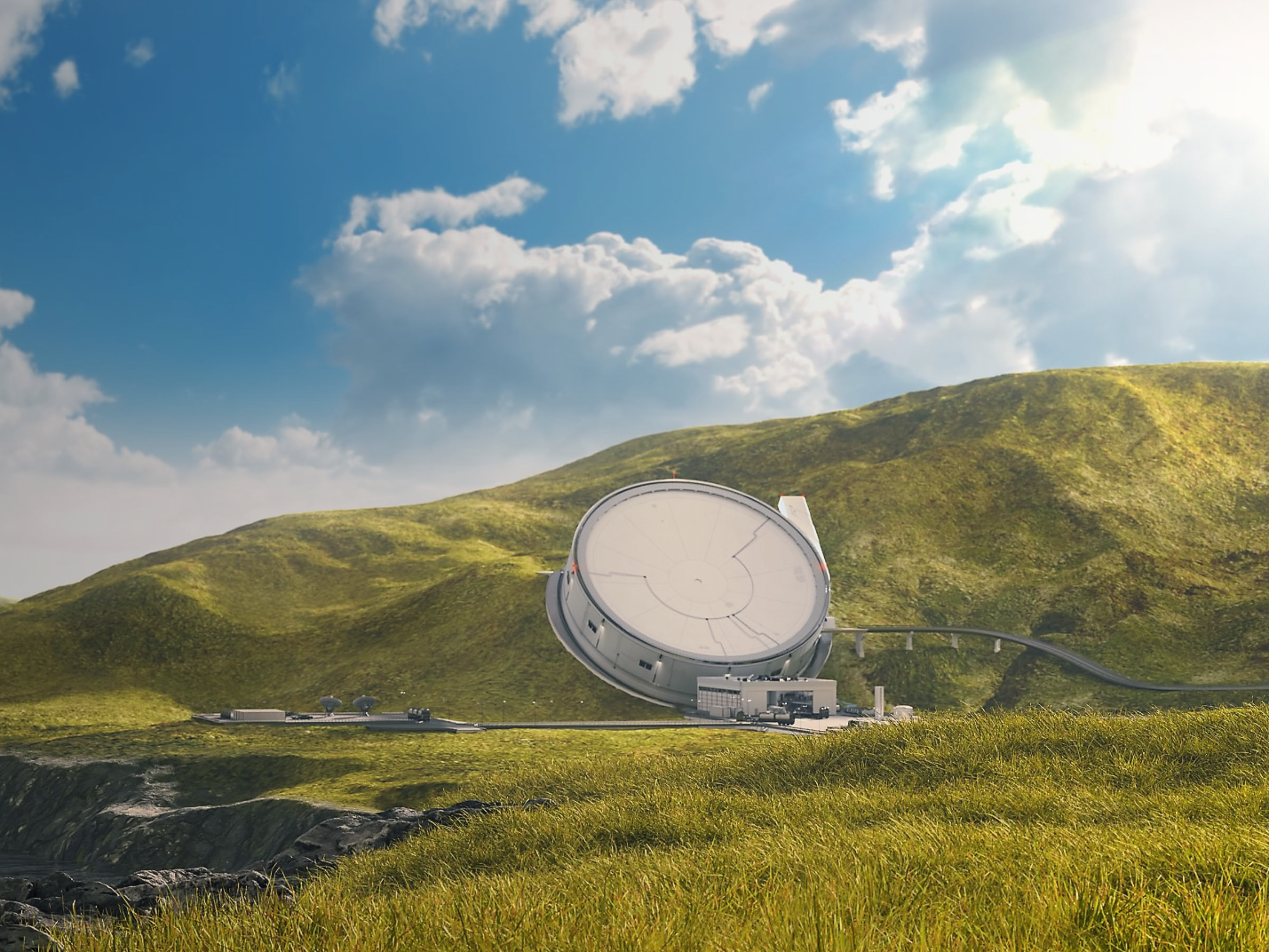

In the desert of New Mexico, engineers are busy building a giant yo-yo-shaped contraption that they hope to use to fling objects into the upper atmosphere.

The suborbital centrifugal launch system, built by California-based SpinLaunch, spins payloads up to speeds of 8,000kph (5,000mph) – more than 6-times the speed of sound – before releasing them. After reaching the upper atmosphere in a matter of seconds, an onboard rocket would then provide the final bit of thrust to make it into orbit. At least that’s the idea.

SpinLaunch claims the cost of sending a satellite into space this way will be less than half a million dollars – roughly 0.5 per cent of the price Inmarsat paid to get its satellite into space earlier this year. The company has already received $71 million in funding to commercialise the technology, as well as secured a launch contract from Nasa.

A prototype of the system has already catapulted test payloads “tens of thousands of feet” into the sky, according to SpinLaunch.

Critics have warned that the amount of centrifugal force involved could damage the satellites, while the speed and size of the spinning machine could result in a catastrophic failure. The method is also incompatible with payloads over 200 kilograms, while any attempt to send a human up would see them black out and die nearly instantly.

Despite these drawbacks, commercialisation of the mass accelerator launcher could potentially be realised relatively soon. SpinLaunch CEO Jonathan Yaney claims the system requires no fundamental advances in material science and can be built using existing hardware. “What started as an innovative idea to make space more accessible has materialised into a technically mature and game-changing approach to launch,” he said last year.

Space elevator

First proposed by a Russian scientist in 1895, a structure that stretches all the way to space could theoretically be used to ferry things into a geosynchronous orbit of Earth.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s proposal, which came after a visit to the Eiffel Tower, imagined a free-standing tower that supported its weight from below, however more recent concepts involve a cable anchored at the equator, with the weight supported by centrifugal forces from above.

Both China and Japan are already developing the technology, with one of Japan’s top construction companies testing carbon nanotubes that could potentially connect Earth to outer space through a 96,000km-long cable.

Travelling at 150km/h, a ‘climber’ device could reach the height of the International Space Station (ISS) in around 2.5 hours – roughly the same time it takes to catch the Eurostar from London to Paris.

Meanwhile China envisions a ‘Sky Ladder’ that could transport a space capsule to a geostationary space station.

Another approach to this concept involves attaching a cable to the surface of the Moon that serves as a ‘Spaceline” back to the upper part of Earth’s atmosphere, allowing planes or even balloons to deliver crew or cargo to it as it circles the globe.

This lunar elevator concept was detailed in a 2019 study from astronomers at the University of Columbia in the US, however similar to the Sky Ladder proposal, it is yet to get off the ground.

Space magnets

The same technology behind maglev trains could be used to create a giant runway, or vacuum tunnel, pointing spacewards.

A maglev-style launch system could provide the initial thrust required to send a rocket hurtling towards space with minimal boosters required. One of the co-inventors of maglev propulsion was even granted a patent in 2001 for a space launch system that positioned the tube system on the slope of a tall mountain.

Another option is to use a magnetic rail gun system, similar to the ones already used by the US Navy to throw their aircraft and pilots into the air from the miniature runways aboard its aircraft carriers. To achieve the same for a space-bound rocket, the electromagnetically-powered rail guns would need to be several kilometres long.

It is not the first time this method has been envisioned to fling things into space, with the 1951 sci-fi classic film When Worlds Collide using this technique. But just like then, this untested launch technique remains a longshot.

Space gun

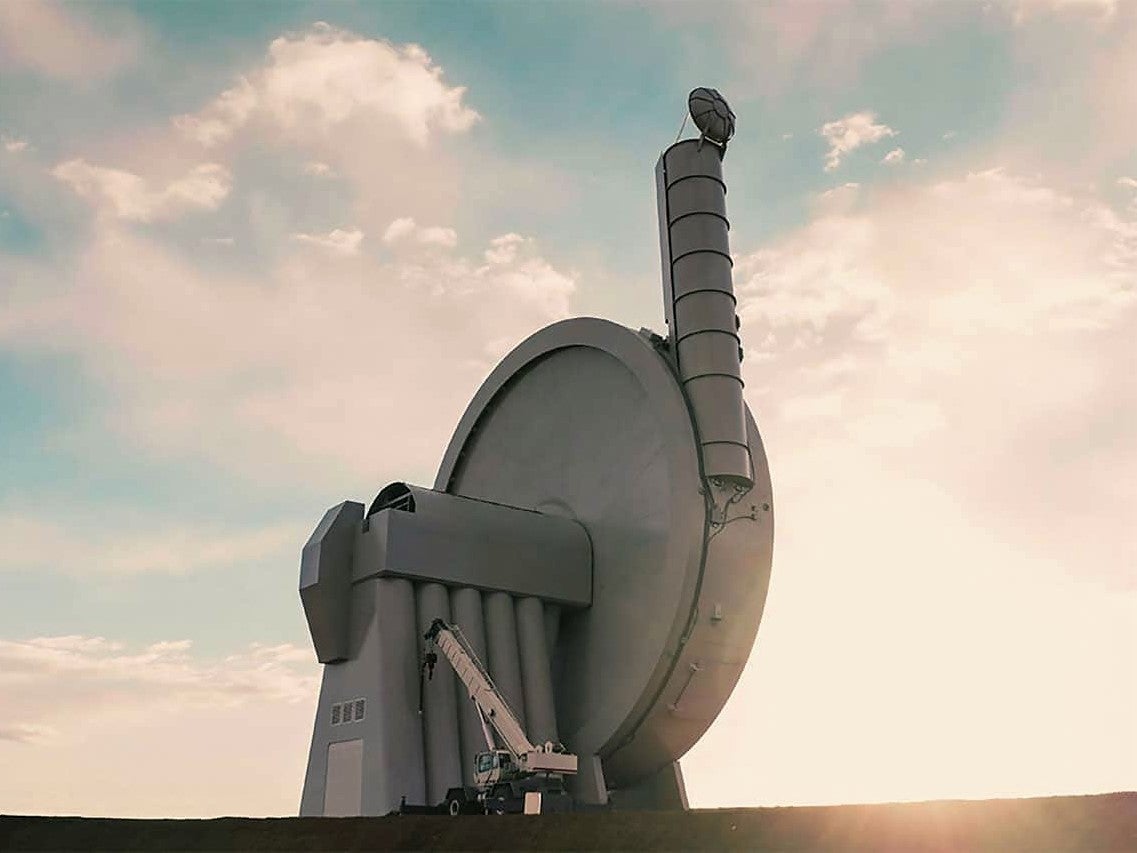

An even more unconventional launch method comes in the form of a space gun, first proposed by inventor John Hunter.

The American projectile researcher developed the idea for a “supergun” called SHARP (Super High Altitude Research Project) at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 1994.

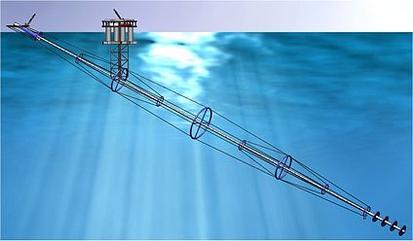

In 2010, Hunter took his idea and formed a startup called Quicklaunch, which he hoped would make a working prototype of the space gun. Using pressurised hydrogen, a 1.1km-long gun would be placed beneath the ocean, with just the muzzle poking above the surface, in order to shoot payloads into space.

The startup collapsed a few years later but Hunter is still working on a modified version of his space gun through his latest project Green Launch. The kilometre-long gun has been replaced with a 122-metre-long cannon, which Green Launch promises can deliver a satellite to orbit in less than 10 minutes.

Sustainable fuels

Beyond carbon-offsetting, this could be the easiest way to achieve sustainability in the short-term.

The space industry currently gets through less than 1 per cent of the fossil fuels burned by the aviation industry, however the cadence of rocket launches has been rapidly increasing in recent years and the impact of releasing pollutants all the way up to the mesosphere and stratosphere in the upper atmosphere are still not properly understood.

Sustainable fuels are already being used in the airline industry, with Virgin Atlantic making the first flight using a low-carbon fuel mix comprised of used cooking oil earlier this week.The airline described it as a “historic moment in aviation’s roadmap to decarbonisation”, however others have called it a “green mirage” as it is not scalable. Even if used cooking oil could work for rockets, this same issue would remain.

Both Nasa and the European Space Agency are conducting research into other “green” propellants, though current consensus is that no fuel-burning rocket will ever be truly clean.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments