‘The holy grail of spaceflight’: Inside the decades-long quest to build a fully reusable spaceplane

Humanity’s dream of an all-in-one spacecraft faded with the Space Shuttle. Now private companies believe they can bring it back, Io Dodds writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

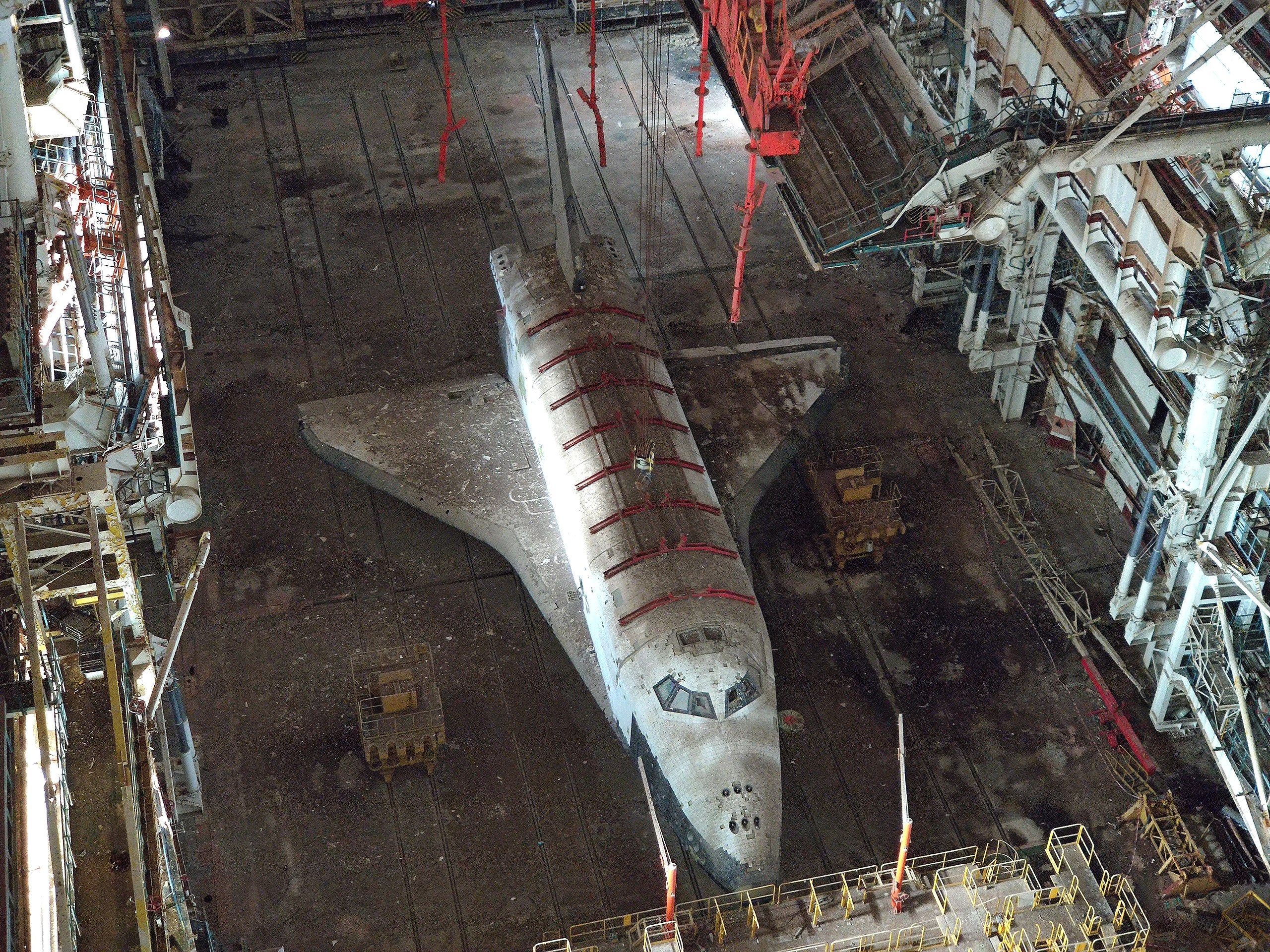

Your support makes all the difference.One day in May 2002, a hanger roof in Kazakhstan collapsed on top of the Soviet Union's only flightworthy spaceplane.

‘Buran’ was a reusable orbiter modeled on America's Space Shuttle. But it ventured into space only once before it was destroyed, along with the lives of eight workers, by poor maintenance and heavy rain.

The orbiter's fate is a sad reminder of how little humanity's hopes for a reusable spaceplane have advanced since the Cold War. For decades, engineers and scientists have dreamed of building a so-called "single-stage to orbit" (SSTO) craft – often described as the Holy Grail of space flight – that could lift off, orbit, and land in one piece without expensive detachable booster rockets.

Those dreams were never realised, and the partially reusable Space Shuttle is now a museum piece, having retired in 2011. Buran's sister ship Ptichka is reportedly in the possession of a Kazakh businessman who says he will only return it to Russia in exchange for the skull of the last Kazakh Khan, who was beheaded in 1847.

But now some companies believe they can make it happen. Earlier this month a Seattle-based start-up called Radian Aerospace exited "stealth" mode earlier and announced it had raised $27.5 million (£20.5 million) from investors. Its plan: to build an SSTO spaceplane that will one day "make space travel nearly as simple and convenient as airliner travel".

"They're right to call it the Holy Grail – we've been calling it that for about forty years," says Mark Hempsell, a former president of the British Interplanetary Society who has worked on multiple spaceplane programmes including the British HOTOL and Skylon projects.

"The lack of improvement in launch vehicles has been like a dam for decades. You release the dam, and then you've got space tourism. More importantly, given everyone's now panicking a bit late in the day over climate change... solar power satellites become viable."

Between here and there is a scorched wasteland of financial and technological obstacles, littered with the burnt-out remains of those who have tried. Crossing it, says Hempsell, will take bleeding-edge ingenuity and vast amounts of money.

The spaceplanes that never were

In 1982, the British government invested in a concept for an uncrewed single stage spaceplane that it hoped would revive Britain's then-fading space programme.

The spaceplane would use a new type of hybrid "air-breathing" jet and rocket engine, designed by the engineer Alan Bond, to take off horizontally from an ordinary runway and then accelerate into space once from high altitude. Hence its name: Horizontal Take-Off and Landing, or HOTOL.

The advantages of such a craft were numerous. The Space Shuttle blasted off vertically, on the back of a giant disposable fuel tank – requiring a new one for every launch, and reusable booster rockets that had to be recovered and refurbished; HOTOL would need only a rocket-powered sled and a horizontal runway, sharply cutting launch costs.

"It's turning getting into space like an aircraft flight," says Hempsell. "You bring it out of the hanger, you fill it up with fuel, take off, go into space, come back, land on the runway, back on the hanger. It makes an enormous difference to what you can do in space."

But HOTOL never happened, and neither did many other proposed SSTO craft. There was the Lockheed Martin X-33 and its big sister the VentureStar, a pair of chunky arrowhead-shaped spaceplanes; the Roton, which would launch vertically then hover back to Earth with helicopter rotor blades; and the Lynx, conceived by the now defunct California firm XCOR Aerospace.

SSTO vehicles are hard, says Hempsell, because of the extreme weight limits they must meet. Unlike multi-stage systems, which discard parts of themselves as they ascend, a spaceplane has to get out of Earth's vicious gravity well as a "complete vehicle", with wings, landing gear, fuel tanks and all.

That all-in-one versatility makes them highly complex too. The Apollo programme that put US astronauts on the moon actually involved four different craft: one to launch into space, one to get to the moon and back, one to visit the surface, and one to bring the crew safely back through Earth's atmosphere.

Apart from the lunar lander, a spaceplane needs to do all of that, from beating gravity to resisting the horrific heat that our atmosphere exerts on falling objects.

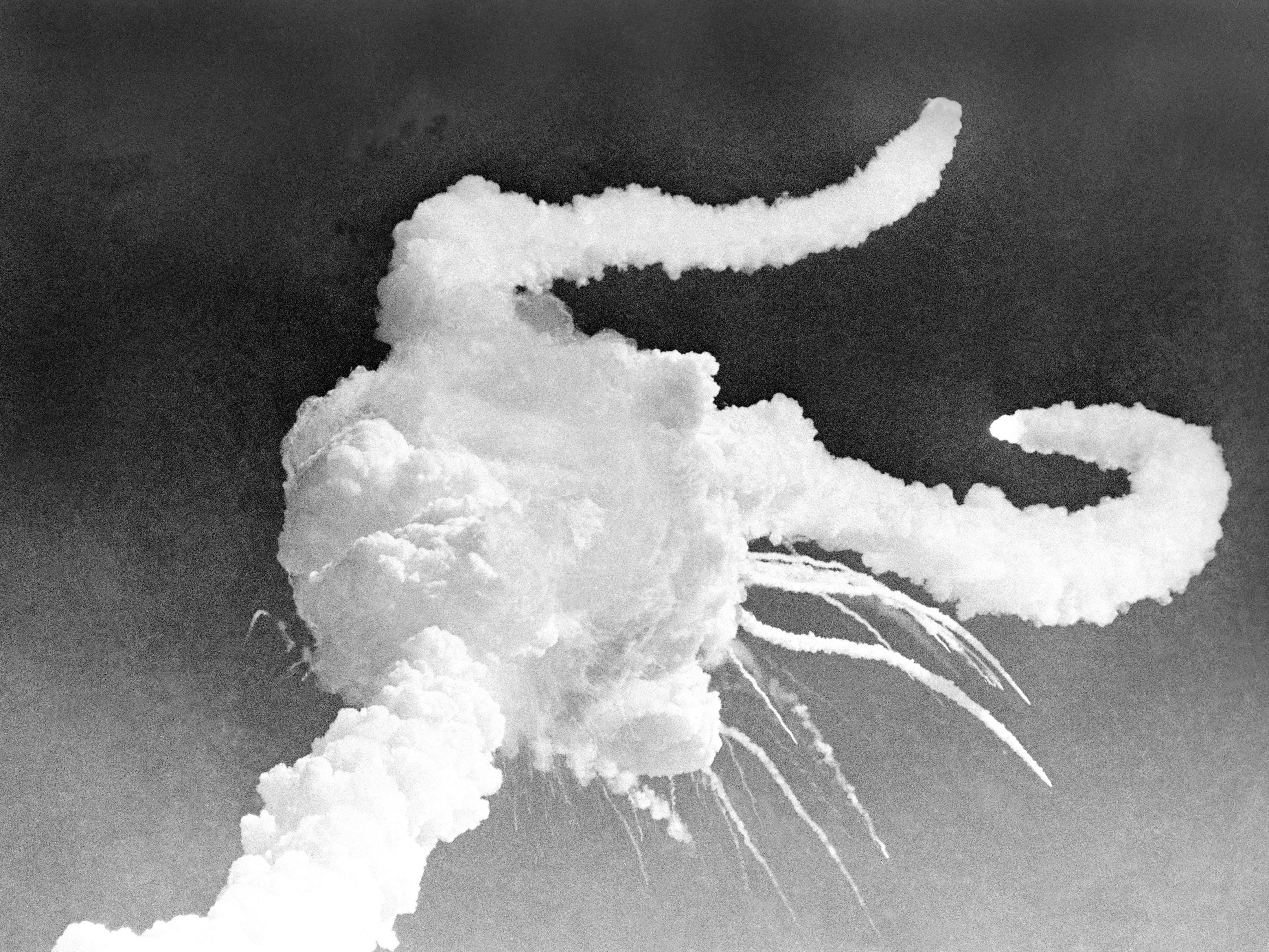

The Space Shuttle illustrates the perils of getting it wrong. In 1986 the shuttle Challenger was destroyed and all seven of its crew killed when one of its booster rockets malfunctioned after lift-off. In 2003, Columbia and its seven crew disintegrated when a small crack opened up in the carbon composite heat shield that protected its wings and underbelly during re-entry.

The new corporate space race

Today, companies such as Elon Musk's SpaceX and Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin have ignited a new corporate race for space. Along with it have come numerous contenders for the spaceplane's unclaimed crown.

Most of these hopefuls are partially reusable craft like the Space Shuttle. Richard Branson's company Virgin Galactic, for instance, launches its SpaceShipOne spaceplane from a conventional aeroplane at high altitude.

“Fully reusable SSTO vehicles need very advanced technology,” says David Ashford, a former member of Hawker Siddeley’s spaceplane design team who published his first paper on the topic in 1965 and whose company Bristol Spaceplanes is seeking funding to build a small two-stage suborbital spaceplane.

“A two-stager can be built sooner and at lower cost and risk, using only proven technology,” he says. “A single-stager can be built later, when the markets and technologies are ready.”

Sierra Nevada, a private US company wholly owned by the Turkish-American billionaire couple Eren and Faitih and Ozmen, is building a mini shuttle called the Dream Chaser that can carry 5.5 tons of cargo and is intended to be compatible with multiple existing vertical launch systems such as the European Space Agency's Ariane rockets.

The firm already has a contract with Nasa to conduct six resupply missions to the International Space Station through 2024. It was the only spaceplane design included in Nasa’s latest round of such contracts, with the others all going to reusable vertical rocket designs such as SpaceX's Falcon lifters.

Governments are also trying to recreate the lost capability. The US has the X-37, a top-secret reusable robotic spaceplane launched inside a conventional rocket, which many fear is intended for military use. China is testing a similar craft known as CSSHQ (the Chinese acronym for "Reusable Experimental Spacecraft"), which has provoked similar speculation.

True SSTO craft are rarer. India is attempting to develop one, though is still in the research and development stage. Meanwhile, Alan Bond's engines and the work on HOTOL ended up in the private sector at Reaction Engines, a British company that is now testing its SABRE air-breathing engines in Colorado.

Rather than trying to build a complete spaceplane, Reaction Engines is focusing on the engines first, which it says have applications beyond space travel. If completed, the engines could make spaceplanes much easier, but flight tests may be a decade away.

Ashford believes it can be done. One of his company’s recent proposals argued: “Early work on spaceplanes [in the Sixties] has never been surpassed, but has largely been forgotten or overlooked.

“Since then, all of the required technologies have been developed for other aeroplanes... what would have been a difficulty and expensive development in the 1960s should therefore now be straightforward.”

Why Radian thinks it can win

Into this treacherous landscape comes Radian, whose chief technology officer Livingston Holder led Boeing's original proposal for the X-33.

"Much has changed between now and then," Holder tells The Independent. "Earlier systems were built around overly aggressive requirements which drove designs to the very limits.

"We can now take advantage of years of advancements in materials science, composite primary structures, durable thermal protection systems, reduction in size, weight and power for both electrical and mechanical components – as well as manufacturing technologies that allow us to go from concept to hardware much faster and make changes much more rapidly."

Like HOTOL, Radian's concept craft would launch via a rocket sled; unlike HOTOL, it is intended as a pure rocket vehicle and will also be crewed to start with. Radian is cagey about further details but says it could be uncrewed in future.

Holder says it will be able to carry 2.5 tons of cargo on the way up and 5 tons on the way down. He lists potential missions such as research crews, Earth observation, and "point to point" transport, meaning flights that only briefly rise into space as a means to cross the Earth very quickly.

Hempsell is sceptical of Radian's announcements. He says many have tried a pure rocket design without succeeding, and argues that there is little point adding the weight of a human crew and its life support systems to every mission when even Buran in the Eighties could orbit and land on autopilot.

He suggests the payload bay shown in Radian's concept art, which is near the nose of the craft and far away from its centre of gravity, would disrupt the craft's trim and create troublesome torque forces. The company says this is a deliberate choice intended to counter-balance the rear-heavy delta wing design.

Hempsell also questions whether the company will have enough money, arguing that spaceplane development costs typically overrun. "$27.5 and a half million barely buys you a hamburger in this game," he says.

Nevertheless, Radian is "confident" it will begin flight tests by the end of this decade.

'Statistics say someone is going to die'

The prizes are great for anyone who can build a viable SSTO. Being able to rapidly launch and re-use the same craft would lower the price of getting into orbit, potentially unlocking space for much wider use.

"When I was a shuttle astronaut the launch process was incredibly difficult," says Clayton Anderson, who spent a total of 167 days in space with Nasa and is now a professor at the University of Iowa.

"The mating of the solid rocket motors to the external tank, and the shuttle to the stack – that could take weeks. It wasn't like buying an airplane ticket, driving to the airport, and in an hour or two you're on a vehicle ready to go from A to B."

Currently the market for space tourism is restricted by the high price of tickets, with Virgin Galactic charging hundreds of thousands of dollars for just a few minutes' hop across the boundary of space while Elon Musk's fully orbital flights are reported to cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Advocates hope that if the prices dropped, the market would expand, making space companies more viable and thereby fuelling the expansion of other industries.

"You're in a completely new game," says Hempsell. "Reliability goes up, safety goes up, so it becomes something that you can offer to the general public as a transport system. It also means you can bring stuff back, which is a facility we've now lost since the space shuttle."

The darker side is that SSTO craft would also be perfect for military use, giving nations the ability to launch satellites, missile interception missions, or even space-based weapons with minimal preparation.

Hempsell still carries the torch for Skylon, a successor to Hotol developed by Reaction Engines that he believes would have been feasible. Today, articles about Skylon have vanished from Reaction Engines' website, and the company now claims it was only theoretical.

"Skylon was the concept vehicle to show how the SABRE engine could be used," business development manager Oliver Nailard told BBC News. "We are not developing a vehicle. In the near term; we are focused on the engine."

In the meantime, Prof Anderson warns that companies trying to exceed Nasa’s grasp should be prepared for deadly turbulence.

"In the Pony Express days, those guys riding horses across the country, people died. In the early days of airplane flight, people died," he says. "But we didn't have social media, where folks find out two seconds later that a plane crashed and killed three hundred people...

"Statistics say that as this is being done, something bad will happen somewhere – just like in 135 Shuttle launches, we killed two crews. What happens when that bad day occurs? Is the market still viable? Are people still willing to invest millions of dollars?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments