Pluto’s surprisingly warm core creates unique ice volcanoes

Pluto possess a rough, ice volcano terrain unlike anything else seen in the Solar System

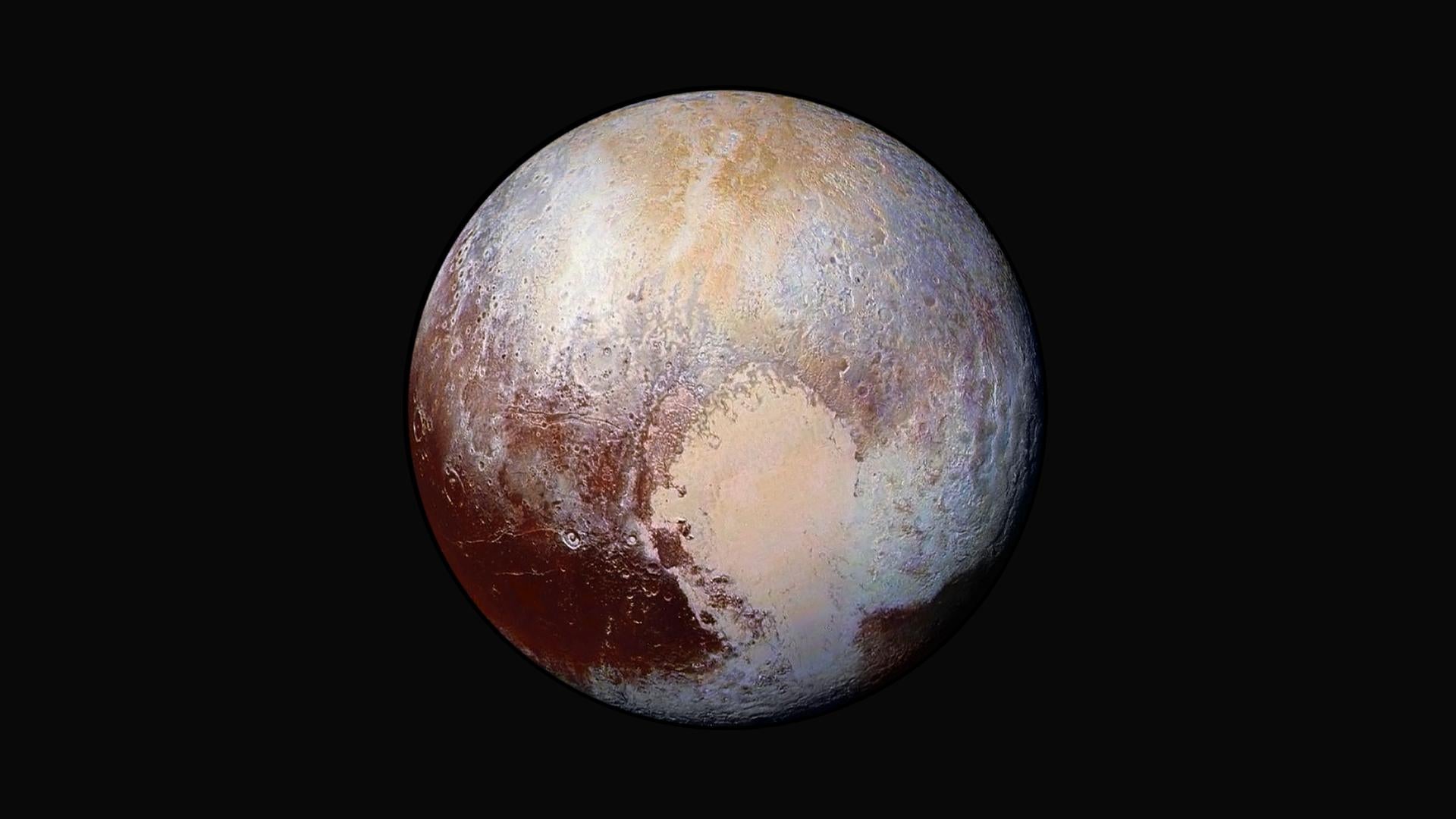

It’s been seven years since Nasa’s New Horizons spacecraft, the fastest vehicle ever launched, screamed by the dwarf planet Pluto, its icy domain 5.9 kilometers from the Sun, but scientists are still learning from the 6.26 gigabytes worth of photos and data gathered during the New Horizons flyby.

The latest New Horizon findings paint a picture of an icy world more active, and slightly warmer, than scientists expected, with the discovery of the most unique region of cryovolcanism in the solar system. A 1,000-kilometer field of large volcanoes spewing ice and ammonia to create a lumpy unlike anything researchers have seen before.

“In terms of icy volcanism, it's by far the largest region that we've seen so far,” said Kelsi Singer, deputy project scientist for New Horizons and senior research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “And it's kind of unique in that it has multiples of these very large structures.”

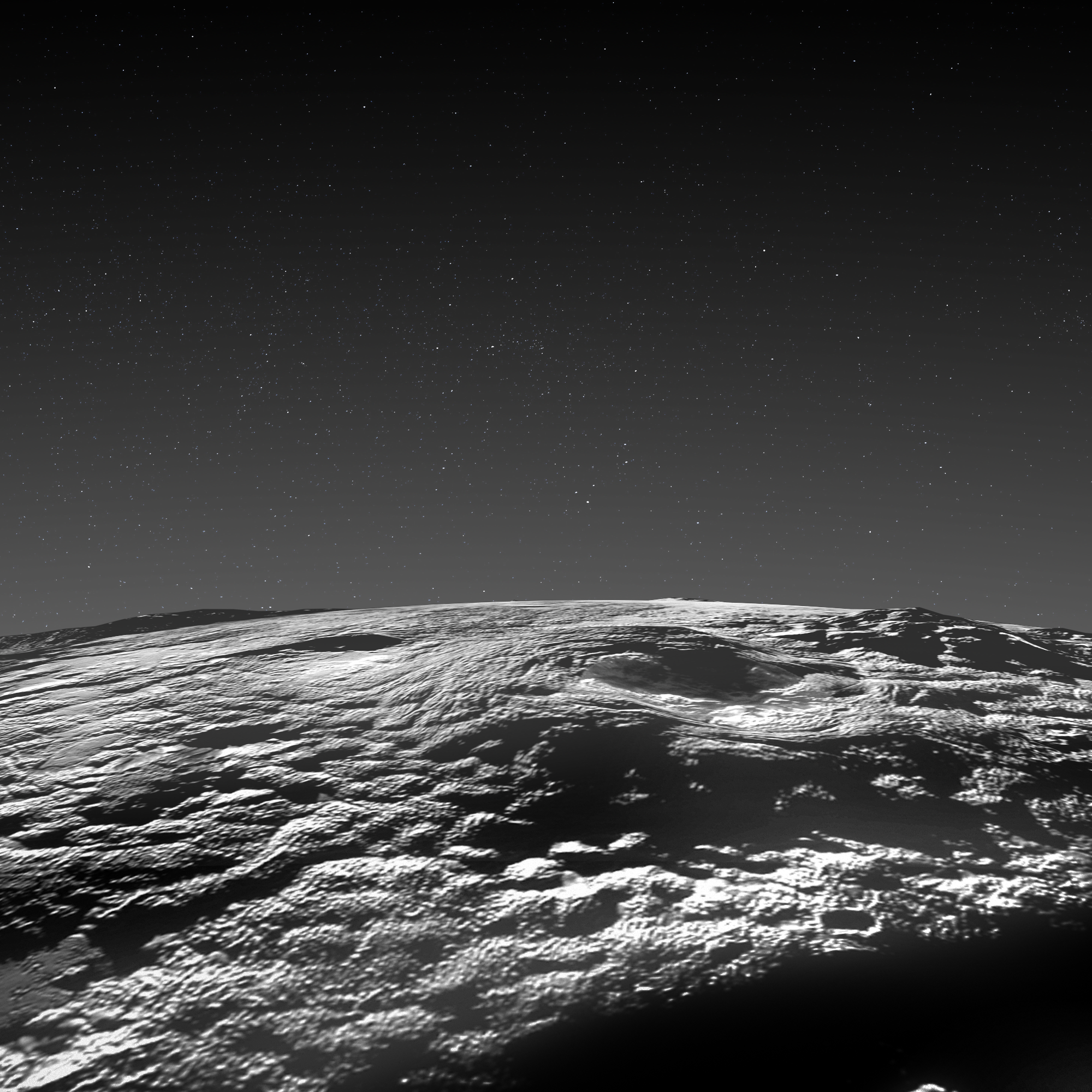

Dr Singer is the lead author of a paper published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. Analyzing images taken from different angles allowed her team to build up a three dimensional topography of the exotic terrain of this region on Pluto and her team’s theories as to how it arose fairly recently on a planet where surface temperatures average minus 229 Celsius.

“Inside of Pluto, the middle two thirds are rocky materials while the outer one third is all icy materials,” Dr Singer said. “So everything you're looking at on the surface is, for the most part, it's mostly icy material.”

In such a cold environment, volcanism like that seen on Earth with molten lava formed of melted rocks, simply cannot exist. Instead, what heat exists at Pluto’s core, combined with certain volatile elements such as ammonia or methanol that reduce the freezing point of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrogen ices underground, which then erupt onto the surface.

“We don't think it was completely melted, because that's just too hard to do on the surface of Pluto,” Dr Singer said. “It was kind of slushy, like an icy-water mixture. Or it could even be kind of like a solid state flow, which is basically what glaciers do.”

The end result is a fascinating landscape of dome-like cryovolcanoes, some as high as seven kilometers tall, to the southwest of the Sputnik Planitia ice sheet, the left lobe of the strikingly heart-shaped Tombaugh region seen in New Horizon images of Pluto.

“We see this very rough terrain at every scale,” Dr Singer said of the cryovolcano field. “There's the giant mounds and then there's the lumps on top of those. And then there's even boulders or other ridges on top of the lumps.”

This contrasts, she said, with cryovolcanic regions seen elsewhere in the solar system, such as Neptune’s Moon Triton, where volcanic regions are very flat surrounding cryovolcanoes. On the dwarf planet Ceres in the main asteroid belt, or on Jupiter’s Moon Europa, meanwhile, cryovolcanoes are more sparse. “They’re not next to each other,” Dr Singer says, “so there’s a lot less material involved and or there's not these giant structures.”

One of the cryovolcanoes analyzed in the paper, Wright Mons, is roughly equal in volume to Hawaii’s Mauna Loa but is much broader than the terrestrial shield volcano, spanning more than 200 kilometers.

Despite this rough, bumpy terrain, one thing conspicuously absent from the cryovolcano field is any sign of impact cratering, a fact that led scientists to conclude the eruptions that created the environment are relatively recent, and could even still be active.

“We cannot say for sure it’s not ongoing, especially if it’s an episodic thing,” Dr Singer said. “Earth’s volcanoes can be dormant for some time and then become active again, and that’s actually pretty common.”

The oldest any portion of the cryovolcano field could date is about 1 billion years, Dr Singer said, “but I would not be surprised if some of it occurred in the last 100 to 200 million years.”

But for that to be true, Pluto would have to have retained more heat within its rocky core for longer than scientists once thought. Understanding the mechanism that allowed Pluto to keep warm at its core for so long in so cold a place will be a topic of ongoing research, but Dr Singer and her team suggest the thick ice of Pluto’s exterior could act as an insulating layer.

“If you're not letting the heat out as easily, you could potentially kind of build it up and then maybe let it out in kind of episodes,” she said. “We see that there was probably more than one episode, there are several indications of that, so it could be kind of an episodic release of this heat if you are able to kind of build it up.”

While analysis of New Horizons Pluto data will continue, a follow up mission to further investigate the mystery of the dwarf planet’s retained warmth is not in the cards any time soon. But Dr Singer noted there are other avenues to better understand how Pluto’s geology functions that could benefit from her team’s findings.

“There's a lot of information about the specific materials that we see on Pluto, and how they might react if you squeeze them or break them, or do different kinds of geologic actions,” she said. “I don't personally work on it, but it's a fun topic.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks