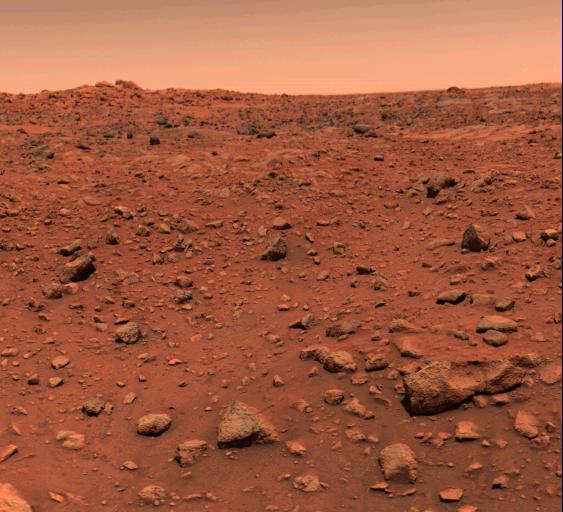

Nasa’s Curiosity rover celebrates its 10th — but hardly last — birthday on Mars

In its decade on Mars, Nasa’s Curiosity rover has helped establish the fact of ancient habitability on the Red Planet, and it’s not even done yet

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Friday, Nasa’s Curiosity rover will celebrate its tenth birthday on Mars, and counting. The small car-sized rover made a soft landing at the bottom of Gale Crater on the evening of 5 August, with a mission to find evidence of past habitability on the Red Planet.

A decade later, Nasa can call Curiosity’s mission a resounding success. It established the long term presence of liquid water on the surface of Mars in the planet’s ancient past, a prerequisite for the existence of life. It also established with certainty the presence of organic chemicals that are the building blocks of potential life.

And moreover, Curiosity’s is a mission that’s still ongoing, with the plucky rover still climbing a mountain of sedimentary rock in what was once an ancient lakebed on Mars.

“About the state of the rover, overall, we’re just thrilled,” Ashwin Vasavada, project scientist for the Curiosity mission, told The Independent. “The rover is still able to do all the science that matters to the mission, even 10 years in.”

Curiosity and the science it enabled serves as an important bridge in Nasa’s Mars science program, connecting earlier missions such as the Spirit and Opportunity Rovers — and even the Viking landers of the 1970s — with the Perseverance rover and Ingenuity helicopter that are also exploring the Red Planet. Perseverance may represent the cutting edge, drilling samples of Martian soil that will be returned to Earth for study in the 2030s, but Curiosity still has much to teach scientists, according to Dr Vasavada.

“There’s still more to come,” he said. “That’s the bottom line.”

Martian curiosity

Curiosity, and Dr Vasavada, really draw their inspiration from the same place — Mars in the 1970s.

“The pictures that really caught me when I was like, 10 years old, were the Viking lander taking pictures of this endless desert landscape going off into the distance,” he said.

Viking 1 landed on Mars on 20 July, 1976, and in addition to taking stunning photos from the surface, conducted the first ever astrobiology experiments on the Red Planet’s surface in hopes of finding evidence of alien life. Mars, after all, combined two very attractive traits for scientists looking for signs of life, according to Dr Vasavada: It carried a decently high chance of having hosted life and was close enough to study.

“There may be places that have a better chance of life, you know, maybe now like oceans on Europa, but they’re too far away to explore efficiently,” he said. “Mars has always had that attraction and the way I like to describe it is like, Viking was the attempt to hit a home run.”

A failed attempt, according to most scientists. Although some scientists still maintain the Viking 1 and 2 landers found evidence of life on Mars, the scientific consensus remains that the Viking results were inconclusive.

“I think if you were to ask planetary scientists in 1977 they would just say, we’re excited because there’s liquid water [on Mars], but we really don’t know much more beyond that,’” Dr Vasavada said. “After that, Nasa really had to regroup for a couple decades.”

It wasn’t until the 1990s, when the space agency made the search for life in the universe a main focus, that Mars research picked up again.

“And they laid out a strategy where they wouldn’t go for the home run anymore,” Dr Vasavada said. Nasa would send orbiters, like the Mars Global Surveyor launched in 1996, to Mars to study the surface and find the best places to land future missions. Then they would send down rovers to confirm evidence that Mars once held large amounts of liquid water.

“If liquid water was never there, there’s no chance life was there,” Dr Vasavada said. “That’s where [the rovers] Spirit and Opportunity fit in. They were really sent there to look for signs of liquid water.”

“The next part of NASA’s strategy was then to broaden the search beyond water to habitability, and that is Curiosity’s main objective,” Dr Vasavada said. Curiosity wouldn’t just look for signs of liquid water, but of persistent liquid water, lakes and rivers flowing long enough for life to have a shot. And it would need to search for the chemical building blocks of life.

“That’s why the rover is kind of large,” Dr Vasavada said. “It has a number of different instruments that look at all these different aspects of what would make a habitable planet. And then we needed to be able to drill into rock samples, because we’re looking in the past.”

Of course, what past you look into depends on where you drill, “So we sent it to Gale crater, which is a 100 mile diameter crater that has a big pile of sediment, sedimentary rock in it,” Dr Vasavada said. “And this was super exciting, because sedimentary rocks record a time history: sediment is laid down progressively over millions of years.”

The hope was that Curiosity could climb a 5km-high pile of sedimentary rocks that had built up in what Nasa believed was an ancient crater lake, drill into the mud rocks, and find evidence of ancient water and organic chemistry.

“So that’s where we were on August 4 of 2012. The day before we landed,” Dr Vasavada said. “We had a great rover, and we had a landing site that offered the best chance we thought of anywhere on the planet of finding a habitable environment, but there were definitely no guarantees.”

Proof of habitability

In the years since its landing 10 years ago, Curiosity has climbed 600m up the sedimentary rock mound in Gale Crater, according to Dr Vasavada.

“What we found is that nearly all of that 600 vertical meters is made of rock layers that have abundant evidence for the interaction with liquid water,” he said. “They’re mud that formed at the bottom.”

It takes time to build up 600m worth of muddy sediment, and so those measurements lead to one of the major discoveries of the Curiosity mission, according to Dr Vasavada: liquid water was present in Gale Crater, on Mars, for a long time.

“It’s like hundreds of thousands of years, but probably more likely millions or tens of millions of years,” he said.

“Tied with that discovery, is the discovery of all of the chemical requirements for life,” Dr Vasavada added. “We were able to drill into these lake bed mudstones, and within those mudstones, we were able to find these organic molecules.”

So three of four billion years ago, in Gale Crater, conditions favorable for life to arise existed on Mars.

“And what’s kind of fascinating is that much of the history that Curiosity has explored predates the time on Earth,” Dr Vasavada said. “Earth became the habitable planet it is today largely after the time period we’re exploring in Gale crater on Mars.”

Four billion years ago, alien scientists passing through our solar system would’ve chosen Mars as the most likely place to find life, not Earth.

Signs of life

But did Mars play host to life all those billions of years ago? That’s not a question Curiosity was designed to answer, but it is one that could be answered by way of Perseverance. Curiosity’s successor landed in a dry riverbed on Mars on 18 February, 2021, and has so far spent its nearly 18 months on the Red Planet drilling rock and soil samples and storing them for later retrieval as part of Nasa’s Sample Return Mission. When the samples are returned to Earth in the 2030s, scientists will be able to bring full laboratories to bear on the question of whether those samples contain signs of Martian life, extant or ancient.

It’s a mission that takes the baton from Curiosity, and a mission that never would have happened with the successes of Curiosity.

“If we found Gale crater was a barren wasteland,” Dr Vasavada said, “If we found a big pile of dust and we were completely wrong in our hypotheses about it prior to landing; It would have been more difficult for Nasa to go ahead with a mission like Perseverance and put all that focus on looking for signs of life.”

But as he mentioned, Curiosity isn’t done yet.

The rover will celebrate its tenth birthday by continuing its slow climb up the sedimentary mound of rocks in Gale Crater, where its most recent samples are beginning to hint at big changes on ancient Mars. Samples that once showed abundant clay minerals now exhibit sulfate rich rocks, according to Dr Vasavada.

“We don’t know what it means but one of our leading hypotheses is that those sulfate minerals were enriched through something like what happens when lakes and water dries out and they leave salty minerals behind,” he said. “It may be a sign of the planet as a whole doing that.”

So as Curiosity roves on, it may not only prove to have found evidence of a past period of habitability, it may provide clues to when and how that period came to an end.

Assuming the tough rover can keep on trucking. Dr Vasavada thinks the odds are good.

“We’ve had some pretty significant challenges. We’ve had to redesign how we drill twice in the mission now due to some anomalies that have occurred and loss of a couple mechanical parts of the rover,“ he said. “We’ve had a lot of issues in 10 years as aging machines do, but we’ve always been able to recover.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments