Nasa rover finds Mars had all ingredients for life

An ancient riverbed and lake once harbored all the necessary ingredients for life, Mars rover scientists say, but it may take an even more ambitious mission to learn if life actually existed there

Ancient Mars had all the right ingredients for life 3.5 billion years ago, but whether life actually swam, burrowed or wriggled on the Red Planet in the ancient past will require bringing Martian rocks to Earth for analysis.

That was the consensus of the NASA scientists behind the space agency’s Perseverance rover mission during a public presentation on the mission’s findings on Thursday.

Since landing on Mars in 2021, Perseverance has drilled rock samples for analysis in what was once once a vast lake on Mars. Those samples have now revealed the presence of both ancient liquid water and organic molecules, the chemical building blocks of life.

“If these conditions existed, I think pretty much anywhere on Earth at any point in time over the last, let’s call it three and a half billion years,” Ken Farely, Perseverance project scientist said at the presentation, “I think it’s safe to say or at least assume that biology would have done its thing and left its mark in these rocks for us to observe.”

Nasa is counting on it: While Perseverance doesn’t carry instruments of determining for certain whether life once existed on Mars, laboratories on Earth do. And Nasa plans to bring the rock samples Perseverance has stored in titanium tubes home to analysis in the early 2030s.

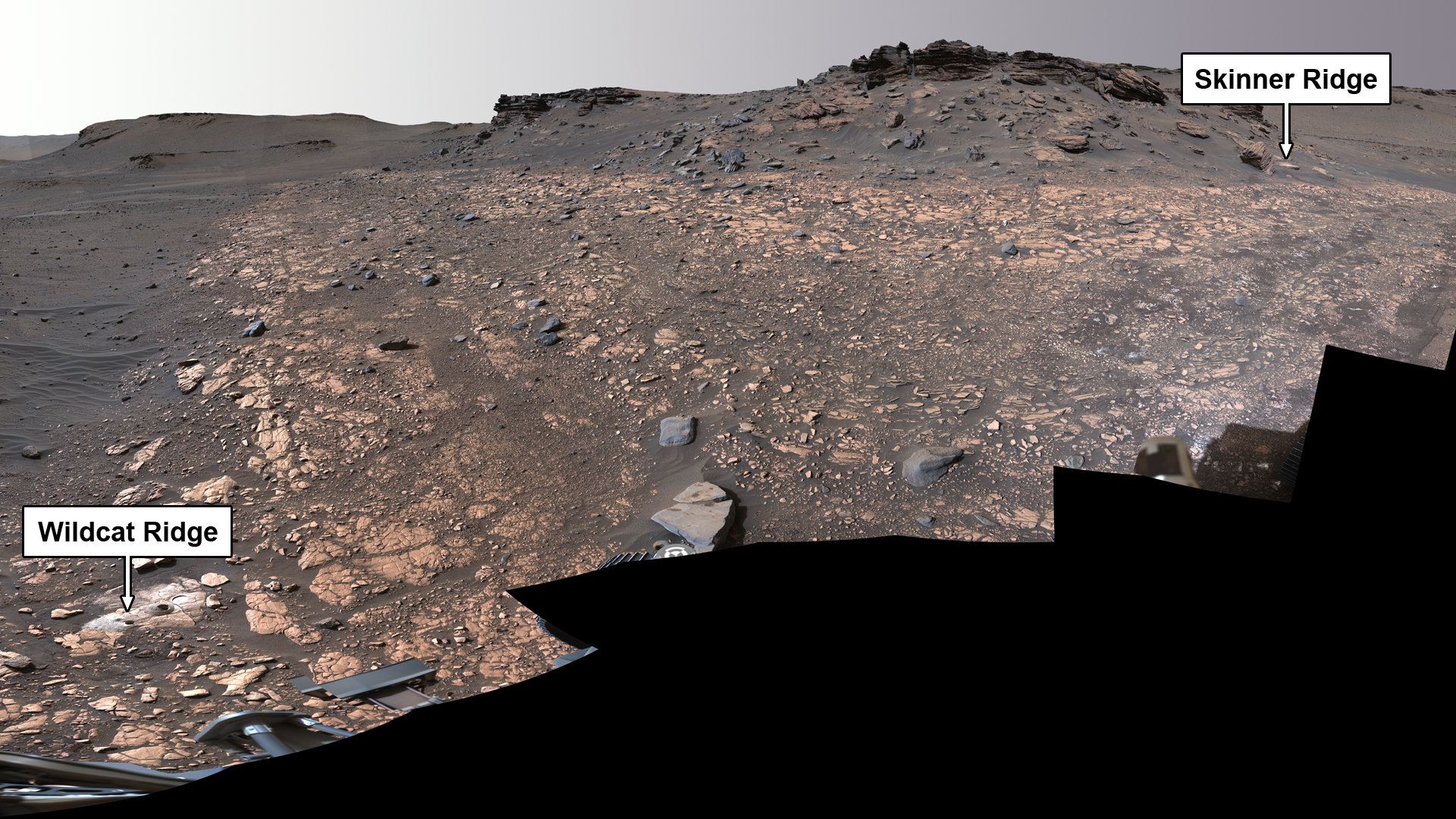

The Perseverance rover landed on Mars on 18 February, 2021, in Jezero crater, a 28-mile wide impact crater that at one point held a vast lake. Since then, the rover has traveled more than eight miles across the ancient lakebed and up into the higher elevations of what was once a river delta, where flowing water once fed the lake and deposited silt from miles away.

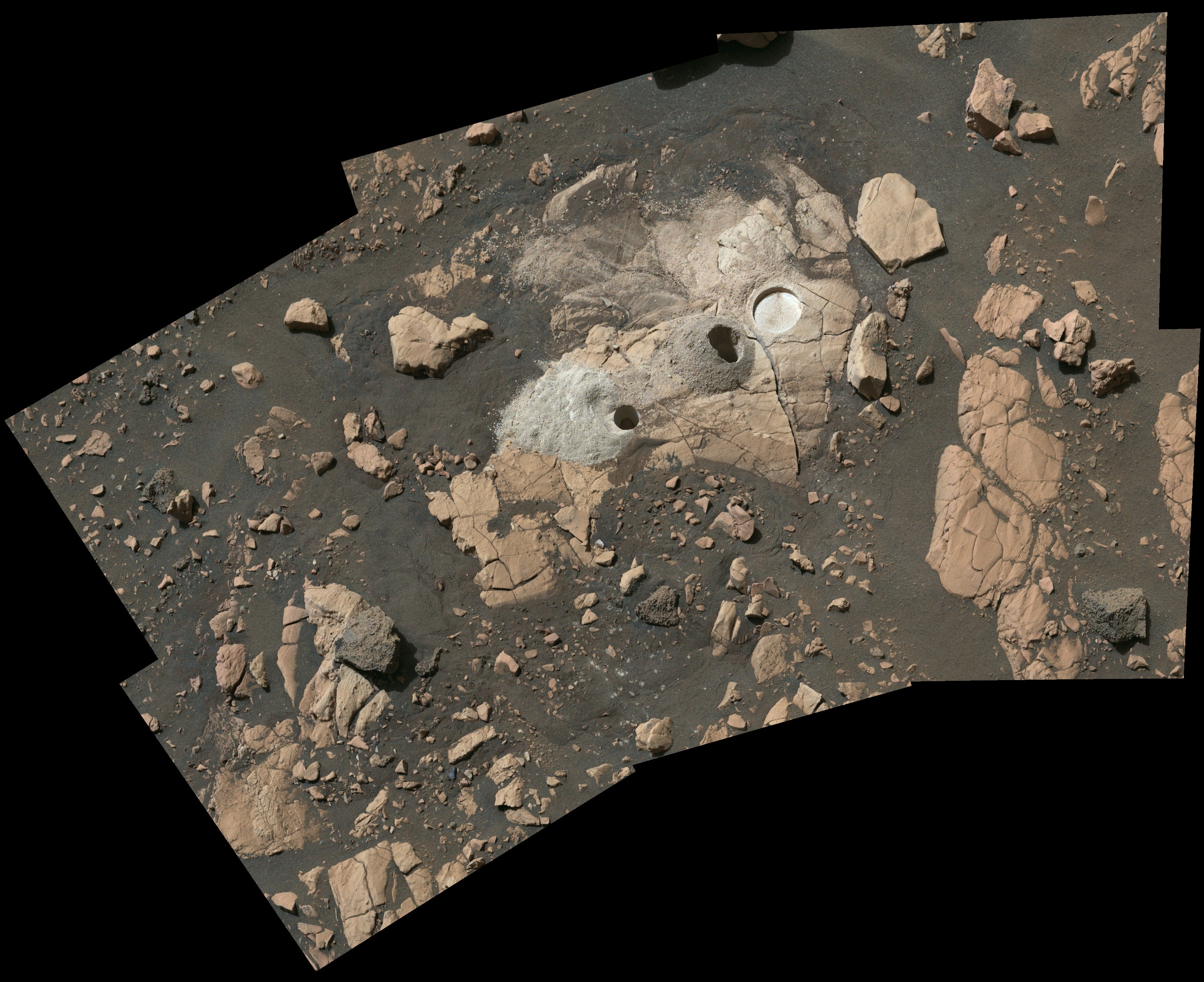

Along the way, Perseverance has selected rocks drill cores from, analyze, and store for retrieval by a later sample return mission.

Perseverance analyzes rocks for organic material using its Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics Chemicals, or Sherloc instrument, which uses an ultraviolet laser to scan for clumps of any organic material present. Sherloc has detected an increasing amount of organic material as it has made its way into the ancient delta region of Jezero crater, Nasa Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) astrobiologist Sunanda Sharma said during Thursday’s presentation.

“If this is a treasure hunt for potential signs of life on another planet, organic matter is a clue, and we’re getting stronger and stronger clues as we’re moving through our delta campaign,” she said.

Two recent Perseverance findings may prove more valuable than any the mission has uncovered so far.

The rover recently took samples from two rocks, Skinner Ridge and Wildcat Ridge, names that are taken from locations in Shenandoah National Park in the US.

Skinner Rock is a sandstone, made from layering of many kinds of rocky material brought from miles away and deposited in the river delta, according to Perseverance Sample Scientist David Shuster. “That’s important because this is giving us some material from a very far distance that the rover will not visit in this mission,” he said.

Wildcat Ridge, meanwhile, is a clay containing mudstone, which likely formed in salty water as the lake in Jezero crater evaporated. It also contained a type of organic matter known as aromatics, “which are stable molecules that are made up of carbon and hydrogen, and sometimes other elements, with ring structures,” Dr Sharma said.

Those aromatic compounds were present in nearly every point where Sherloc scanned Wildcat Ride material.

Importantly, WildCat ridge also contains sulfate, which has implications for what information it might preserve about ancient life on Mars, if it existed.

“The organic signals are also most strongly correlated to a mineral called sulfate that we saw on the rock,” Dr Sharma said. “On Earth, sulfate deposits are known to preserve organics and can harbor signs of life, which are called bio signatures. This makes these samples and this set of observations some of themselves intriguing.”

The finding builds on the results of other Nasa missions, including the ongoing Curiosity rover mission, which first detected signs of organic compounds in a different part of Mars in 2013.

“I personally find these results so moving,” Dr Sharma said, “because it feels like we’re in the right place with the right tools at a very pivotal moment.”

Neither Perseverance or Curiosity contain enough instrumentation to determine with certainty whether or not life ever existed on Mars, but terrestrial laboratories might. This is why Perseverance has been collecting rock samples and storing them in tubes for retrieval by the joint Nasa-European Space Agency Mars Sample Return Mission.

Scheduled to launch in 2028, the sample return mission will collect the samples from either caches on the Martian surface, or from Perseverance directly if the rover is still operational. Those samples will make it back to Earth in 2033.

“We can bring these rocks back to Earth, where we can query them in the most sophisticated laboratories that we have, so that we can get at answering some of the biggest questions that we as scientists can ask,” JPL Director Laurie Leshin said at the presentation. Whatever the results, “we will learn so much.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks