Solar Orbiter images capture the Sun like never before

One eye-catching feature captured by the spacecraft has been nicknamed ‘the hedgehog’.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Powerful flares, views across the solar poles, and a curious solar “hedgehog” are among the latest haul of images from the Solar Orbiter.

The spacecraft’s closest approach to the Sun, known as perihelion, took place on March 26, taking it inside the orbit of Mercury, at about one-third the distance from the Sun to the Earth.

David Berghmans, from the Royal Observatory of Belgium, and the principal investigator of the extreme ultraviolet imager (EUI) instrument, which takes high-resolution images of the lower layers of the Sun’s atmosphere, known as the solar corona, described the images as “really breathtaking”.

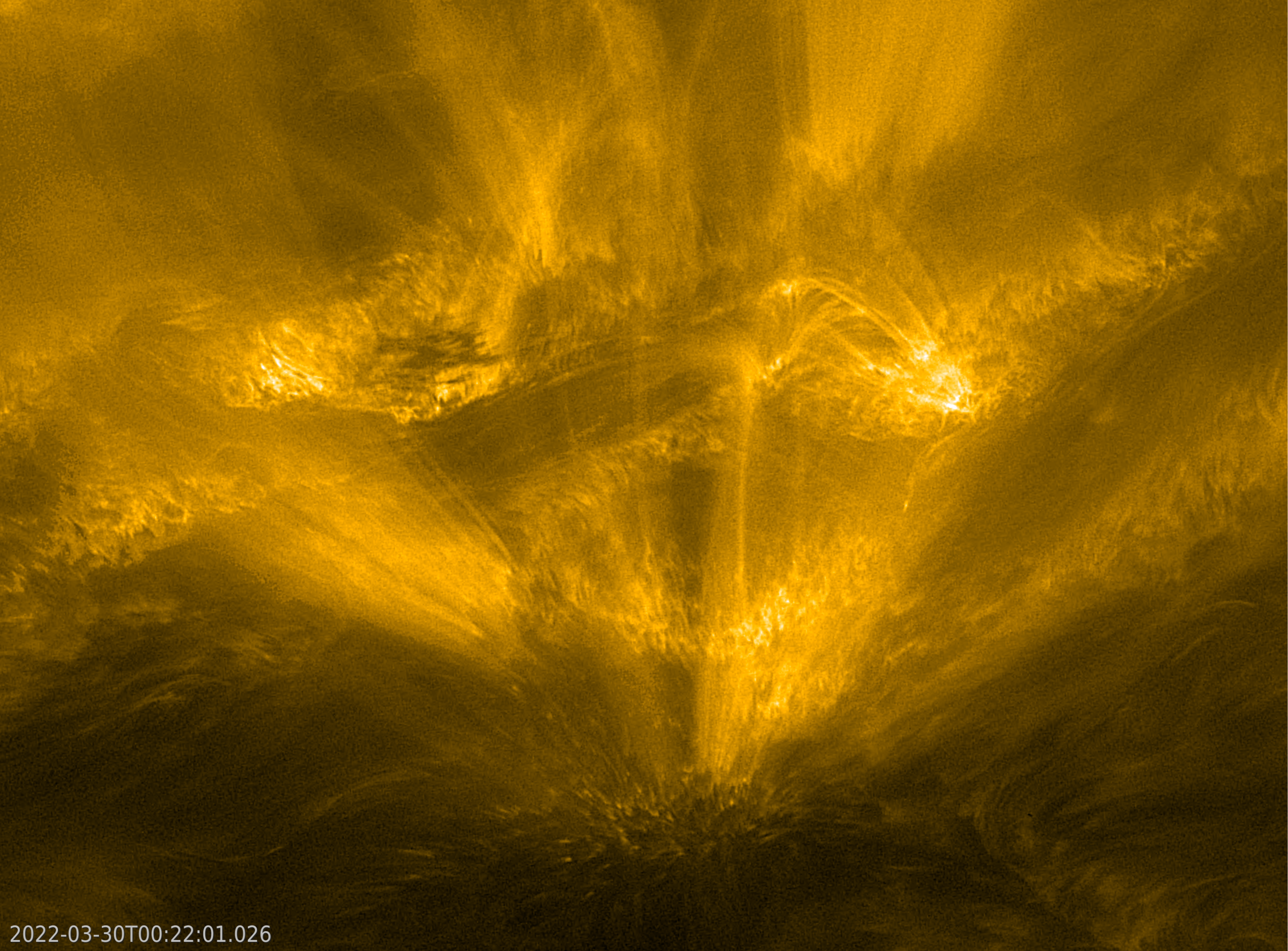

One eye-catching feature captured by the spacecraft has been nicknamed “the hedgehog”.

It stretches 25,000 kilometres across the Sun and has a multitude of spikes of hot and colder gas that reach out in all directions.

As something the EUI team cannot immediately recognise, they must dig through past solar observations by other space missions to see if anything similar has been seen before, in order to understand what they are seeing.

During the perihelion the spacecraft also soaked up several solar flares, providing a taste of real-time space weather forecasting.

This is becoming increasingly important because of the threat space weather poses to technology and astronauts.

Caroline Harper, head of space science at the UK Space Agency, said: “It’s hugely exciting to see these incredible images and footage; the closest we’ve ever seen of the Sun, captured during Solar Orbiter’s nearest pass so far.

We are already seeing some fascinating data being returned from the science instruments on board this UK-built spacecraft, bringing us closer to understanding how natural events on the Sun’s surface contribute to space weather

“We are already seeing some fascinating data being returned from the science instruments on board this UK-built spacecraft, bringing us closer to understanding how natural events on the Sun’s surface contribute to space weather.

“Not only are we learning from the images that Solar Orbiter is sending back, but also from what it ‘feels’ as it gets closer to the Sun, including solar flares and a recent coronal mass ejection.”

The Solar Orbiter carries 10 science instruments – nine are led by European Space Agency member states and one by Nasa – all working together to provide unprecedented insight into how the Sun works.

The orbiter’s main science goal is to explore the connection between the Sun and the heliosphere – the large bubble of space that extends beyond the planets of our Solar System.

It is filled with electrically charged particles, most of which have been expelled by the Sun to form the solar wind.

It is the movement of these particles and the associated solar magnetic fields that create space weather.

The next – and slightly closer – perihelion pass will take place on October 13 at 0.29 times the Earth-Sun distance.

Before then, on September 4, it will make its third flyby of Venus.