Astronomers observe aftermath of Nasa mission to crash spacecraft into asteroid

As well as a test of planetary defence, the Dart mission gave astronomers a chance to learn more about the Dimorphos asteroid.

Astronomers have observed the aftermath of the collision involving a spacecraft sent by Nasa to crash into an asteroid.

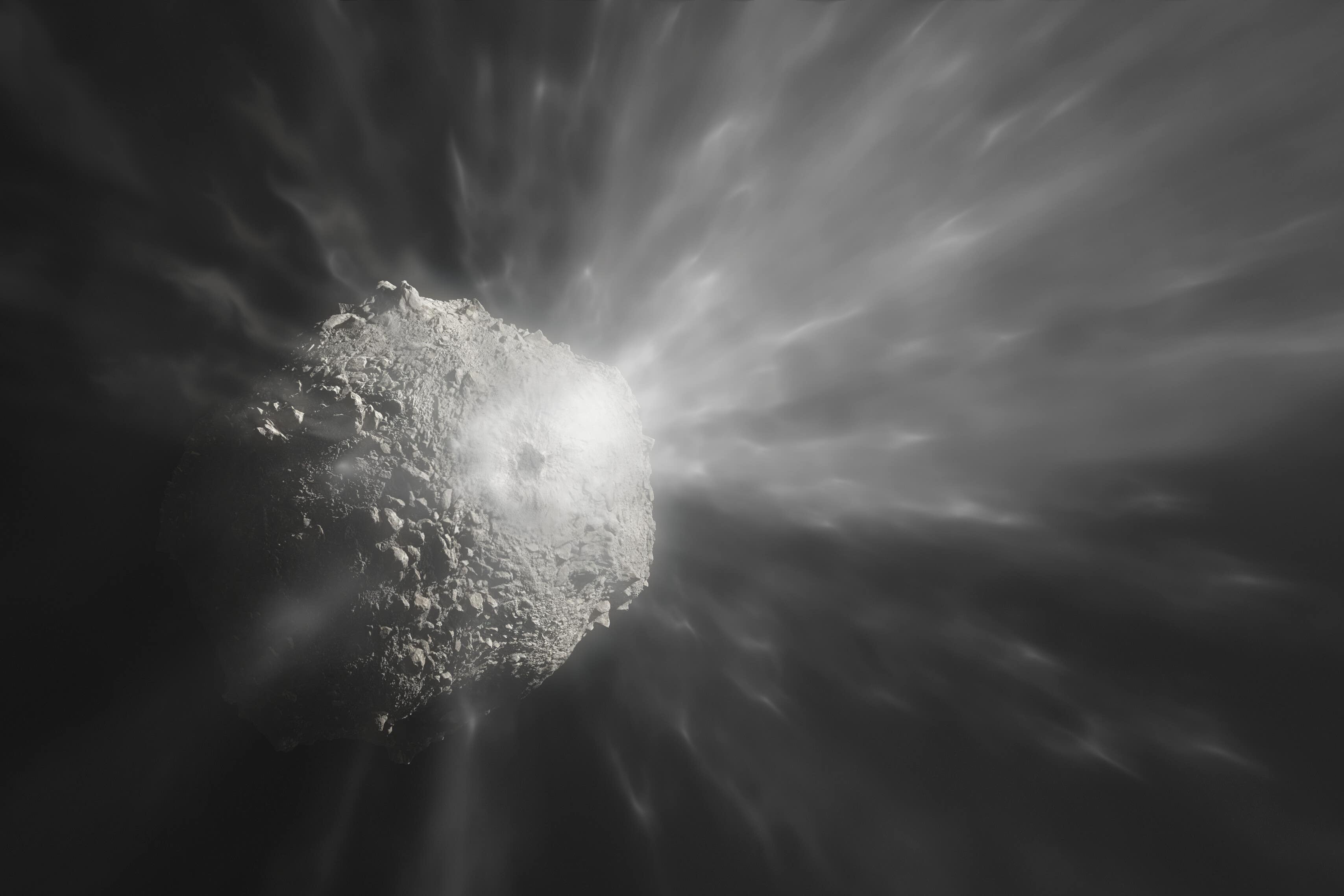

The controlled impact was a test of planetary defence, but also gave astronomers a chance to learn more about the Dimorphos asteroid by examining the material expelled.

On September 26 last year, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (Dart) spacecraft smashed into the asteroid some 11 million kilometres away from Earth.

Asteroids are some of the most basic relics of what all the planets and moons in our solar system were created from

This was close enough to be observed in detail with many telescopes. All four 8.2-metre telescopes of European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile observed the aftermath of the impact.

Brian Murphy, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh and co-author of one of the two studies reporting the observations, said: “Asteroids are some of the most basic relics of what all the planets and moons in our solar system were created from.”

Experts suggest studying the cloud of material ejected after Dart’s impact can therefore yield clues about how the solar system formed.

“Impacts between asteroids happen naturally, but you never know it in advance,” added Cyrielle Opitom, an astronomer also at the University of Edinburgh and lead author of one of the articles.

“Dart is a really great opportunity to study a controlled impact, almost as in a laboratory.”

Researchers followed the evolution of the cloud of debris for a month and found that the ejected cloud was bluer than the asteroid itself before the impact.

They suggest this indicates the cloud could be made of very fine particles.

Asteroids are not expected to contain significant amounts of ice, so detecting any trace of water would have been a real surprise

In the hours and days after the impact other structures developed, including clumps, spirals and a long tail pushed away by the sun’s radiation.

The spirals and tail were redder than the initial cloud, and so could be made of larger particles, the scientist say.

The researchers specifically looked for oxygen and water coming from ice exposed by the impact. But they found nothing.

Dr Opitom explained: “Asteroids are not expected to contain significant amounts of ice, so detecting any trace of water would have been a real surprise.”

They also looked for traces of the propellant of the Dart spacecraft, but found none.

Dr Opitom added: “We knew it was a long shot as the amount of gas that would be left in the tanks from the propulsion system would not be huge.

“Furthermore, some of it would have travelled too far to detect it with Muse (Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer instrument) by the time we started observing.”

Another team, led by Stefano Bagnulo, an astronomer at the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium in the UK, studied how the Dart impact altered the surface of the asteroid.

He said: “When we observe the objects in our solar system, we are looking at the sunlight that is scattered by their surface or by their atmosphere, which becomes partially polarised.

“How the polarisation changes with the orientation of the asteroid relative to us and the sun reveals the structure and composition of its surface.”

The researchers found that the level of polarisation suddenly dropped after the impact.

At the same time, the overall brightness of the system increased, possibly caused by the impact exposing more pristine material from inside the asteroid

The findings are published in the journals Astronomy & Astrophysics, and Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks