Scientists decode what happened when the moon once ‘turned itself inside out’

Analysing variations in moon’s gravity allowed researchers to peek under its surface

Scientists have finally discovered the sequence of events that likely led to the Earth’s moon turning itself inside out billions of years ago.

Most of what researchers know about the moon’s origin and its geology comes from analysis of rocks collected by Apollo astronauts which show surprisingly high concentrations of titanium.

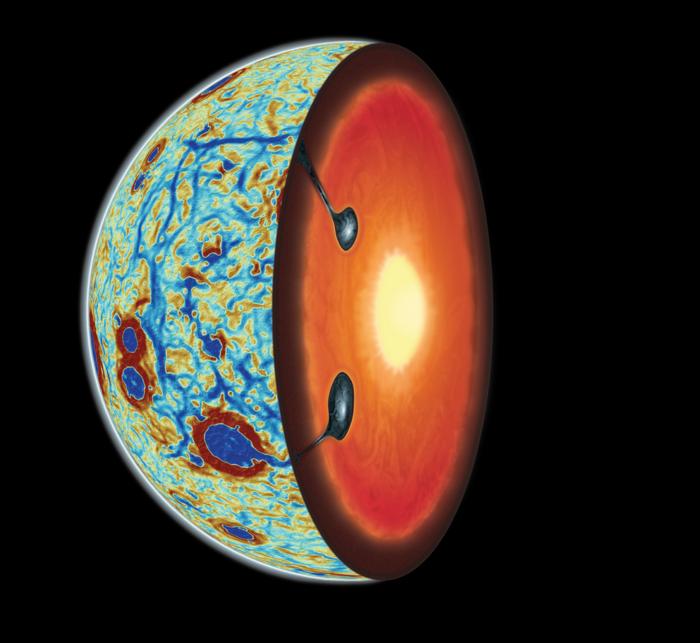

Researchers suspect that when the moon formed around 4.5 billion years ago when another massive body in the solar system smashed into Earth, it was initially hot and covered by a global magma ocean.

But how it came to be the form that we currently see today when we look up at night has remained a mystery.

As the molten rock gradually cooled, it formed the moon’s mantle and the bright crust, but deeper below, it was wildly out of equilibrium.

Here, the magma ocean crystallised into dense minerals including ilmenite – a mineral containing titanium and iron.

But somehow this dense material that sank into the interior, mixed with the mantle, melted and returned to the surface.

However, how and why these titanium-rich volcanic rocks got to the moon’s surface is unknown.

It remains unclear if this material sank all at once or a little at a time as smaller blobs.

Scientists have yet to fully understand how some of the titanium-rich material that sank within the interior of the moon rose to its nearside – the lunar hemisphere that always faces towards Earth.

“Our moon literally turned itself inside out,” Jeff Andrews-Hanna, another author of the study, said.

“For the first time, we have physical evidence showing us what was happening in the moon’s interior during this critical stage of its evolution, and that’s really exciting,” Dr Andrews-Hanna said.

To understand how the moon flipped inside out researchers assessed simulations of a sinking ilmenite-rich layer on it.

They then compared the observations to a set of linear gravity anomalies detected by Nasa’s Grail mission, whose two spacecraft orbited the moon between 2011 and 2012, measuring tiny variations in its gravitational pull.

These linear anomalies surround a vast dark region of the moon’s nearside covered by volcanic flows known as mare – Latin for “sea.”

Scientists found that gravity signatures measured by the Grail mission are consistent with ilmenite layer simulations.

They could use the gravity field to map out the distribution of the ilmenite remnants left after the sinking of the majority of the dense layer.

This suggests that the Ilmenite materials migrated to the moon’s near side and sunk into the interior in sheetlike cascades, “leaving behind a vestige that causes anomalies in the moon’s gravity field, as seen by Grail,” researchers noted.

“Because these heavy minerals are denser than the mantle underneath, it creates a gravitational instability, and you would expect this layer to sink deeper into the moon’s interior,” study co-author Weigang Liang said.

Based on these findings, scientists say the ilmenite-rich layer sank over 4.22 billion years ago – consistent with it contributing to later volcanism seen on the lunar surface.

“It turns out that the moon’s earliest history is written below the surface, and it just took the right combination of models and data to unveil that story,” Dr Andrews-Hanna said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks