Massive solar eruption this week will not strike Earth

Although Tuesday’s solar eruption pointed away from Earth and will not impact our planet or any satellites, it’s an example of the type of solar activity that could become more likely in the coming years.

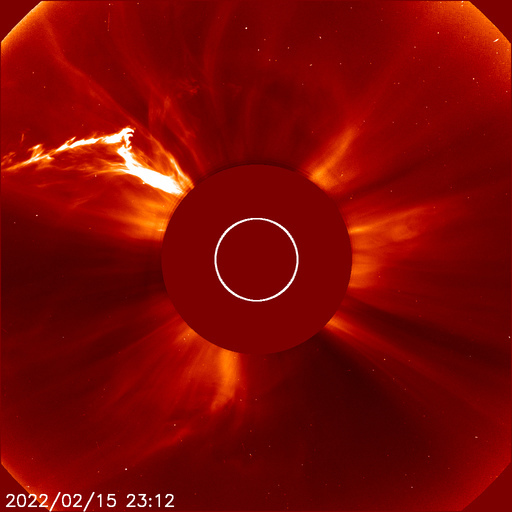

Nasa solar satellites captured a massive eruption on the far-side sun late Tuesday evening, a coronal mass ejection that flung immense amounts of plasma and radiation out into space.

The coronal mass ejection comes eruption comes just days after a similar eruption triggered a geomagnetic storm on 4 February that dragged 40 newly launched SpaceX Starlink satellites out of their orbits.

Since Tuesday’s eruption took place on the far side of the sun, it will not trigger a geomagnetic storm or pose a hazard to satellites, but the coronal mass ejection is indicative of a sun that is growing more active. Coronal mass ejections can carry charged plasma and magnetic fields out into space as fast as 3,000 kilometers per second, and reach Earth in 15 to 18 hours.

On Wednesday morning, ESA scientist Mark McCaughrean shared a short video of the coronal mass ejection captured by instruments aboard Nasa’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO mission.

The #solarcycle25 Dr McCaughrean added refers to the 25th solar sunspot cycle since astronomers began counting these 10 to 11 year periods in the 19th century. The dark spots on the sun’s surface known as sunspots are intimately tied to our star’s magnetic activity, which waxes and wanes throughout each roughly decade-long cycle.

When the sun’s magnetic activity is increasing as it is right now — the peak of solar cycle 25 activity is executed around 2025 — magnetic field lines become tangled, energized, and more likely to snap, causing eruptions like those of 4 February and Tuesday evening. So while satellite operators can breathe a sigh of relief over this most recent eruption, they are really just entering the space weather woods rather than leaving them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks