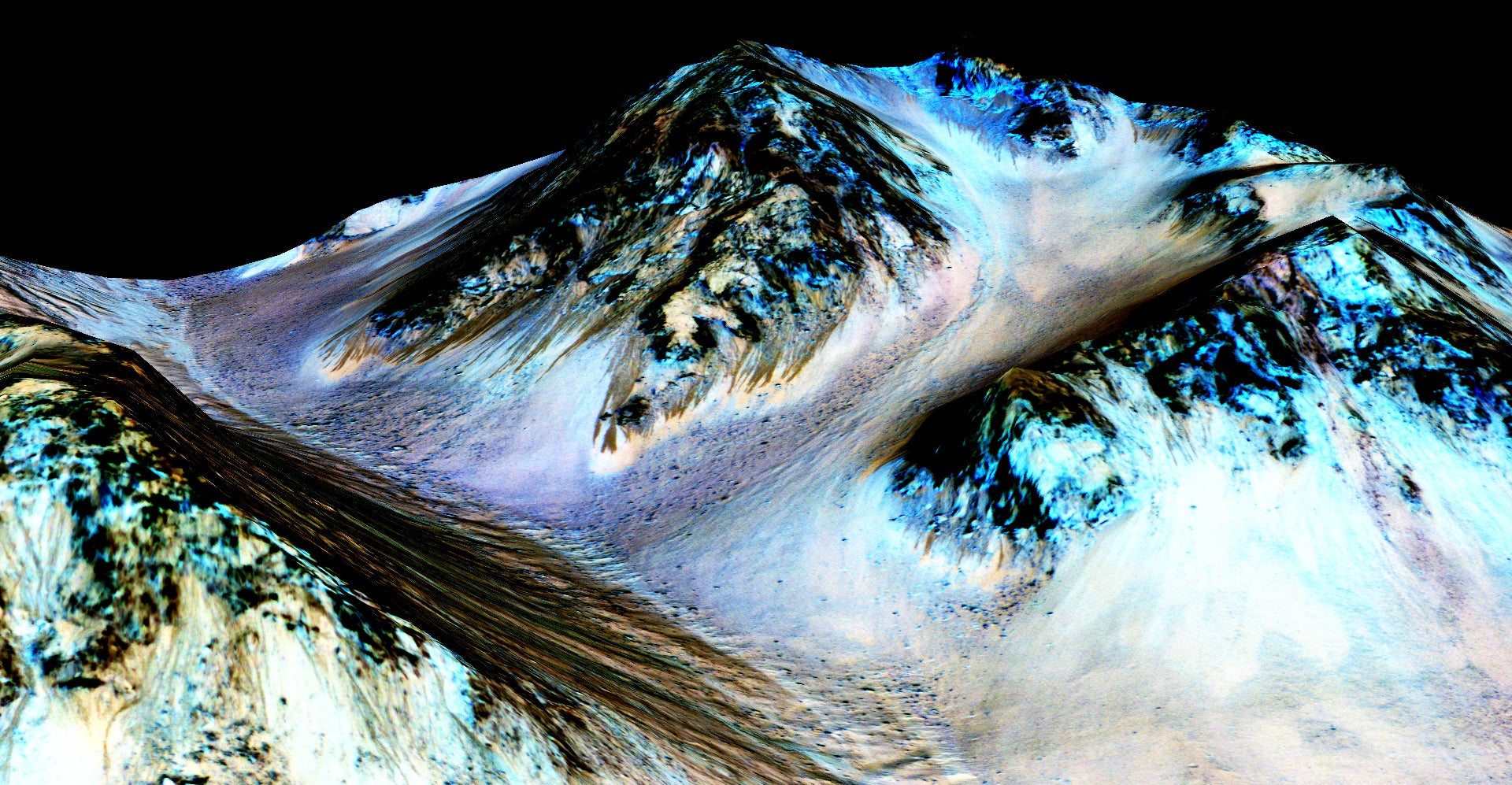

Clay, not water, likely source of subsurface lakes on Mars, study says

A type of frozen clay can produce the same kind of radar reflections thought to be evidence of water

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A form of clay known as smectite and not water as earlier thought, could be responsible for bright radar reflections from the south pole of Mars, according to new research.

Some scientists point out that there has always been scepticism about the theory that the Red Planet’s south pole is home to subsurface lakes.

The new research, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters on 29 July, however, shows credible evidence that the signals interpreted as evidence of water, can actually be indicative of smectites.

According to the scientists, including those from York University in Canada, smectites are a class of clay formed when the volcanic rock basalt that comprises most of Mars’ surface, breaks down chemically in the presence of liquid water.

The researchers showed that smectites are found in the Martian south pole and can better explain radar observations made by the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) instrument aboard the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Mars Express orbiter.

Their analysis found frozen smectites can produce the kind of radar reflections recorded by the instrument.

“In the past few years, there have been a couple of studies that interpreted radar data to indicate that there are liquid water lakes underneath the ice cap at the south pole of Mars. If true, that is revolutionary for our understanding of Martian habitability. So, we decided to test that hypothesis,” Jennifer Whitten, a co-author of the study from Tulane University, said in a statement.

“Our paper explores other scenarios that could produce that same signal and concludes that the presence of clay below the ice cap is more likely given the conditions on Mars today,” Ms Whitten added.

Smectites are abundant on Mars and cover about half the planet, especially the southern hemisphere, according to Isaac Smith, the lead author of the study and an assistant professor of earth and space science at York University.

“That knowledge, along with the radar properties of smectites at cryogenic temperatures, points to them being the most likely explanation to the riddle,” Mr Smith said in a statement.

Earlier studies had speculated that liquid lakes could be present in the region due to the presence of large quantities of salt and heat to thaw ice at the bottom of the polar cap.

Recent analysis, however, found that similar radar reflections could be detected from places where ice is more difficult to thaw as well, raising doubts about the idea.

“Based on observations, the first reason the bright reflectors cannot be water is because some of them continue from underground onto the surface. If that is the case, then we should see springs, which we don’t,” Stefano Nerozzi, a postdoctoral fellow in the University of Arizona in the US, said in a statement.

“Not only that, but multiple reflectors are stacked on top of each other, and some are even found right in the middle of the polar cap. If this were water, this would be physically impossible,” Mr Nerozzi added.

The liquid water theory requires incredible amounts of heat – six to eight times more than Mars provides – and more salt than Mars has, according to the scientists.

“So while our work shows that there may not be liquid water and an associated habitable environment for life under the cap today, it does tell us about water that existed in this area in the past,” Briony Horgan, one of the study’s co-authors from Purdue University, said in a statement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments