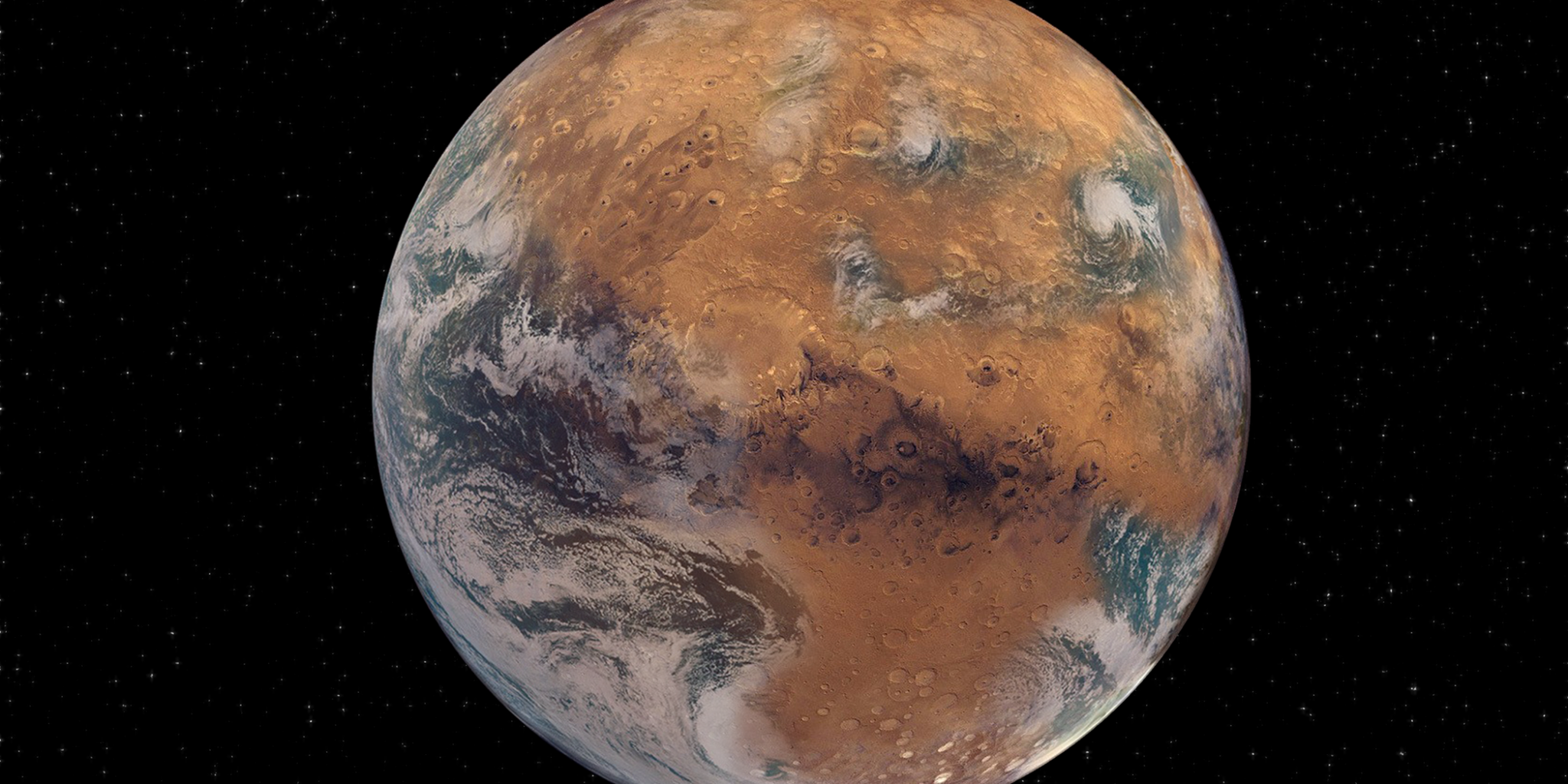

Mars is too small to have aliens, scientists suggest

The Red Planet may not be large enough to hold the bodies of water necessary to form life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mars may have never been able to home alien life because the planet is too small to hold large amounts of water, researchers have theorised.

The presence of water is vital for the evolution of life, and the search for evidence of liquid has inspired probes and studies of the Red Planet to confirm that humanity is not alone in the universe.

Our closest planetary neighbour, however, has revealed no liquid water on its surface, and scientists may now know why. “Mars’ fate was decided from the beginning,” said Kun Wang, assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts and Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“There is likely a threshold on the size requirements of rocky planets to retain enough water to enable habitability and plate tectonics, with mass exceeding that of Mars.”

Professor Wang and those working with him used stable isotopes of potassium to estimate the presence and distribution of volatile elements and compounds – such as water – on the planet, by measuring its composition in 20 confirmed Martian meteorites.

They found that Mars lost more potassium, and other volatiles, than Earth when it was formed – but contained more than the Moon and another asteroid called 4-Vesta, both of which are smaller and drier than Mars.

“It’s indisputable that there used to be liquid water on the surface of Mars, but how much water in total Mars once had is hard to quantify through remote sensing and rover studies alone,” Professor Wang said.

“There are many models out there for the bulk water content of Mars. In some of them, early Mars was even wetter than the Earth. We don’t believe that was the case.”

Being too close to the sun can have a significant effect on the number of volatiles a planet can hold, and suggests that the size range for planets to have the perfect ratio of water for a habitable surface environment is more limited than previous thoughts.

Scientists hunting for alien life in the future should use planetary size as a more important reference than previously thought, Professor Wang suggests.

“The size of an exoplanet is one of the parameters that is easiest to determine,” Professor Wang said. “Based on size and mass, we now know whether an exoplanet is a candidate for life, because a first-order determining factor for volatile retention is size.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments