Stargazing in January: Mars in focus

Despite decades of research, life on the red planet remains one of the deep mysteries of space, Nigel Henbest writes

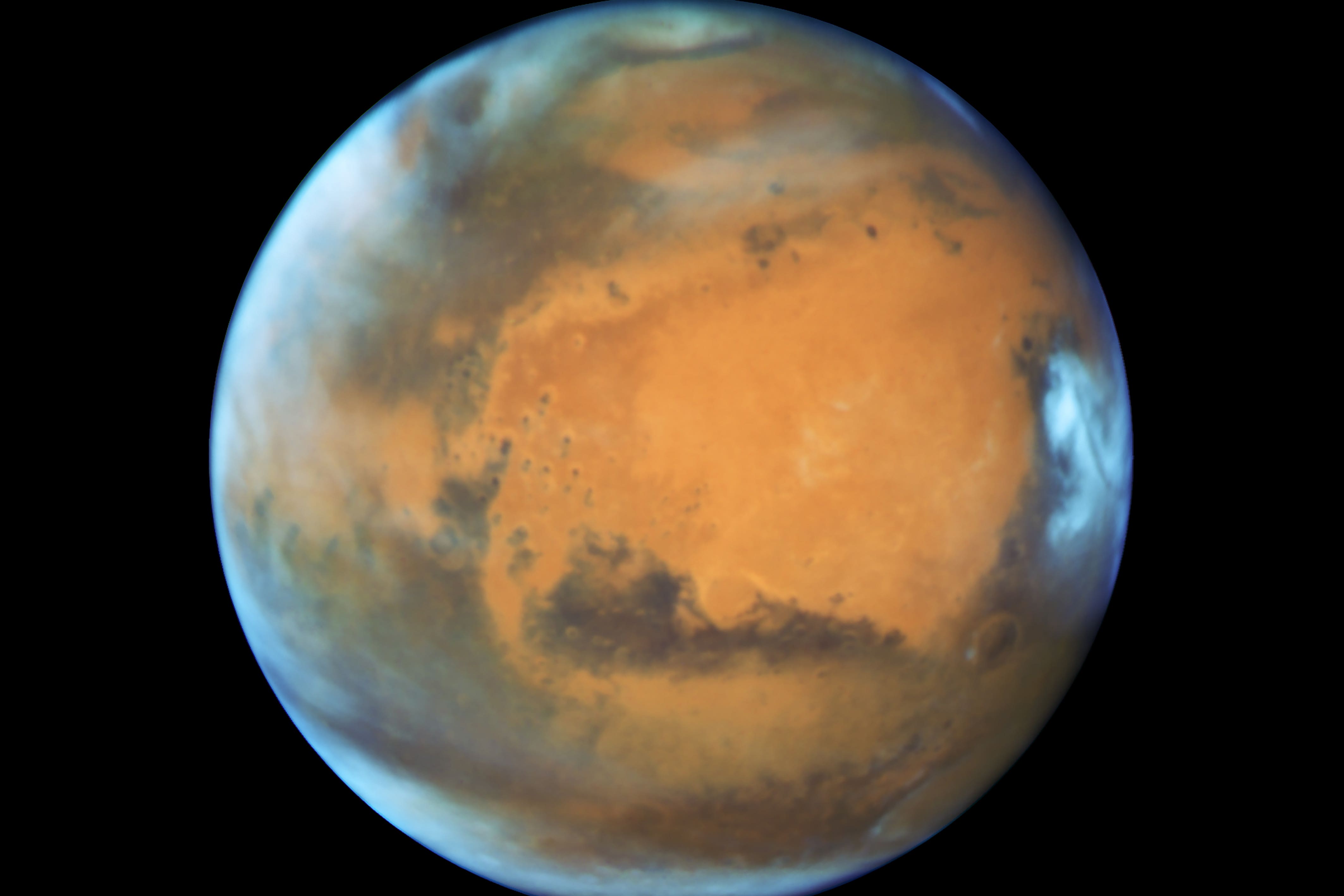

Is there life on Mars?

It’s bright, it’s red, it’s mysterious – and it’s closest to Earth this month! After two years away in the nether reaches of its orbit, Mars returns centre-stage in January.

You’ll find the "red planet" high in the south these chilly winter evenings. It’s one of two brilliant celestial lights, slightly dimmer and definitely ruddier than Jupiter. Mars reaches its maximum brightness on 12 January when it’s nearest to Earth – a "mere" 96 million kilometres away.

Through a moderately powerful telescope, you can see that Mars is a barren smaller brother of the Earth, completely covered by reddish deserts and sporting frozen white polar caps. But lying farther from the Sun, Mars is a colder world, and the polar caps are largely composed of frozen carbon dioxide. With an atmosphere less than one-hundredth as thick as ours, and no protective magnetic field, Mars’s surface is exposed to lethal radiation from space.

It's a place where most terrestrial life – including humans – would quickly turn up its toes and die. But scientists have long believed that Mars could be the nearest abode of extra-terrestrial life – not little green men, but colonies of bacteria or other simple lifeforms.

Despite decades of research, life on Mars remains one of the deep mysteries of space. The first spacecraft to land on the red deserts, the Viking landers of 1976, checked out the soil for signs of life – but the results were ambiguous. In one case, the soil sample emitted gases when water and nutrients were provided – like yeast in a fermenting vat on Earth – but other experiments came up with negative results.

None of the many subsequent missions have directly checked for life on the red planet. But NASA’s latest rovers, Curiosity and Perseverance, have found plenty of organic molecules – the building blocks of life – in the Martian deserts. Add the fact that Mars’s climate was warmer and wetter in the past, and there’s a good chance that living cells evolved there just as they did on the Earth.

Perseverance has been drilling out samples of rocks containing organic molecules – and just possibly living or fossilised cells – and caching them on Mars’s surface for a future mission to bring back to Earth, where scientists can prise out their innermost secrets in the lab. But there’s just one hitch. So far, no-one has funded a mission to travel to Mars and bring these precious samples home.

In the meantime, European scientists are about to send a dedicated life-detection mission to Mars. Rosalind Franklin is named after the British scientist whose experiments led directly to the unravelling of the structure of the life-molecule DNA. Due for launch in 2028, the mission will check the Martian soil for the remains of past or – hopefully – extant living cells.

These robotic missions may, however, be upstaged. Space entrepreneur Elon Musk has developed his giant Starship rocket with the goal of sending humans to Mars within the next few years. Until recently, space experts have judged this plan to be overly optimistic.

But later this month, Musk will have a powerful ally in the White House. In a 2024 election campaign speech in Wilmington, North Carolina, Donald Trump exhorted: “Elon, get those rocketships going, because we want to reach Mars before the end of my term!” Trump’s Wilmington speech may turn out to be the equivalent of President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 oration at Rice University, Texas, in which he declared “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Launch windows to the red planet open every two years: the next opportunity is in 2026, when Musk plans to send five uncrewed Starships to Mars to prepare for a human mission that would launch at the end of 2028. The search for Martian life would be given a boost if a robotic Starship mission were to pick up and return the Perseverance samples as a dry run for returning humans to Earth. Or – just maybe - an astronaut in 2029 may chance upon Martian life in an interesting rock that happens to catch their eye as they stroll across the planet’s red deserts.

What’s Up

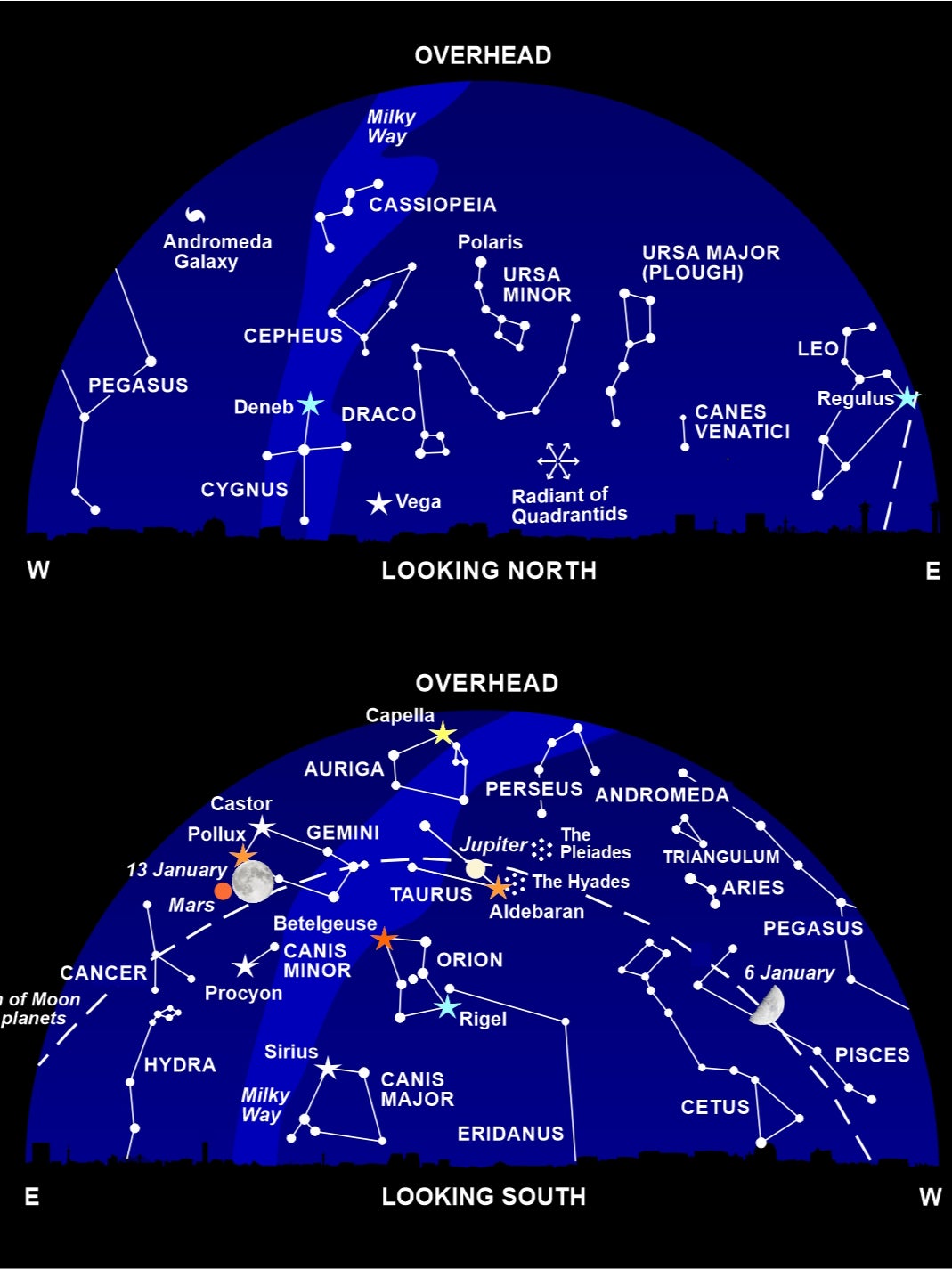

We have an action-packed start to 2025, with the Moon, planets and shooting stars headlining the New Year show – plus the three brightest planets putting in guest appearances.

First up, the crescent Moon passes close to brilliant Venus in the evening sky on 3 January. The beautiful Evening Star is second in brightness only to the Moon, and a small telescope shows it as a half-lit globe.

Stay up later that night (3 to 4 January) for a celestial firework display, as shooting stars stream outwards from a point in the sky near the "tail" of the Great Bear (Ursa Major). Here, astronomers once depicted the constellation of Quadrans Muralis (the mural quadrant); while both this archaic astronomical instrument and its eponymous star pattern have long been retired, the name lives on in the annual Quadrantid meteor shower, known for its bright multi-coloured shooting stars.

And there’s more action on the evening of 4 January, as the Moon moves in front of Saturn in a rare planetary occultation. Saturn disappears behind the Moon about 5.15pm (the exact time depending on your location), and reappears about 6.25pm.

A few days later, in the early morning hours of 10 January the Moon moves in front of the Pleiades star cluster, blotting out four of the cluster’s brightest stars, the Seven Sisters. That evening, the Moon passes close to Jupiter, the second most brilliant planet.

Almost rivalling Jupiter in brightness. Mars (see main story) is at its closest to Earth for two years on 12 January, with the Full Moon passing nearby on the night of 13 to 14 January: people in North America and western Africa will see the Moon pass directly in front of Mars. The Red Planet is directly in line with the Sun and Earth on 16 January.

And let’s not forget the scintillating winter stars and constellations on view this month, including magnificent Orion and Sirius, the most brilliant star in the heavens.

3 January: Moon near Venus; maximum of Quadrantid meteor shower

4 January: Earth at perihelion; Moon occults Saturn

6 January, 11.56pm: First Quarter Moon

10 January, 1.30am to 4am: Moon occults the Pleiades

10 January, evening: Venus at greatest elongation east; Moon near Jupiter

12 January: Mars closest to Earth

13 January, 10.27pm: Full Moon near Mars

16 January: Mars at opposition near Regulus

18 January: Venus near Saturn

21 January, 8.31pm: Last Quarter Moon

29 January, 12.36pm: New Moon

Nigel Henbest’s ‘Stargazing 2025’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything happening in the night sky next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments