Martian microbes could survive for millions of years underground, scientists say

The durability of Earthly microbes in Mars-like environments suggests Martian life could persist on the Red Planet — and that humans must take care not to contaminate Mars with bacteria from Earth

Some microorganisms could survive the harsh climate of Mars for up to hundreds of millions of years, according to new research, a finding that could have many implications for the search for life on the Red Planet.

A team of researchers from across the US and Slovenia, including Northwest University professor of chemistry Brian Hoffman, created a simulated Mars environment with cold, arid temperatures and high levels of radiation exposure, and found that certain strains of Earthly bacteria survived longer than expected. It’s a finding that suggests that any ancient Martian microbes, if they ever existed, could still live beneath the Martian soil, and that humans need to be very careful about contaminating Mars with terrestrial microbes.

A paper detailing their results was published Tuesday in the journal Astrobiology.

“We concluded that terrestrial contamination on Mars would essentially be permanent — over time frames of thousands of years,” Dr Hoffman said in a statement. “This could complicate scientific efforts to look for Martian life. Likewise, if microbes evolved on Mars, they could be capable of surviving until present day. That means returning Mars samples could contaminate Earth.”

Mars as we know it today is very dry, and very cold, with average temperatures hovering around negative 80 degrees Fahrenheit, and even colder at the poles. Since it lacks a magnetic field like Earth, Mars is also bombarded by radiation from both the Sun and the greater cosmos.

“There is no flowing water or significant water in the Martian atmosphere, so cells and spores would dry out,” Dr Hoffman said. “It also is known that the surface temperature on Mars is roughly similar to dry ice, so it is indeed deeply frozen.”

So he and his colleagues created similar conditions in a lab on Earth and subjected six types of terrestrial bacteria and fungi to gamma ray and proton radiation.

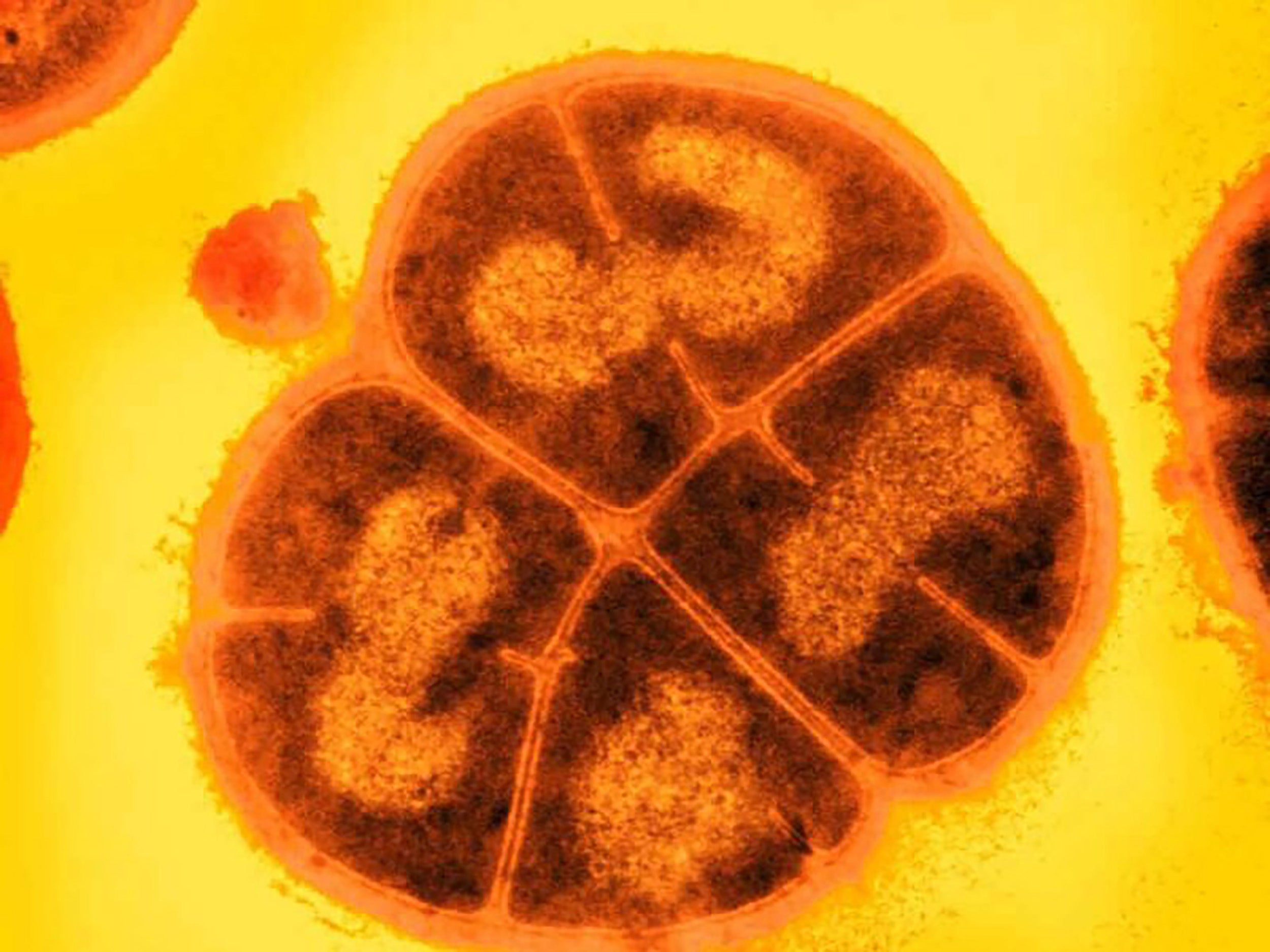

One bacteria strain, Deinococcus radiodurans, lived up to its nickname, “Conan the Bacterium.” The researchers found it could absorb a dose of radiation 28,000 times the lethal dose for humans when buried under the equivalent of Martian soil. The researchers estimate it could survive for 1.5 million years at just 10 centimeters beneath the Red Planet’s surface, a lifespan that could increase to as much as 280 million years if buried a full 10 meters beneath the surface.

If a similar bacterium evolved on Mars, scientists wouldn’t expect it to have survived the 2 to 2.5 billion years since water flowed freely on the Marian surface, according to Michael Daly, a professor of pathology at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda Maryland and the leader of the study. But periodic meteorite impacts could have melted enough water from time to time to provide such microorganisms oases in time.

“We suggest that periodic melting could allow intermittent repopulation and dispersal,” Dr Daly said in a statement. “That strengthens the probability that, if life ever evolved on Mars, this will be revealed in future missions.”

Missions such as Nasa Mars sample return, which will bring samples of Martian soil taken by the space agency’s Perseverance rover back to Earth in the early 2030s.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks