An ongoing galactic tug of war could change our understanding of how galaxies die, scientists say

Some galaxies may die in slow motion, choking without more gas to form new stars

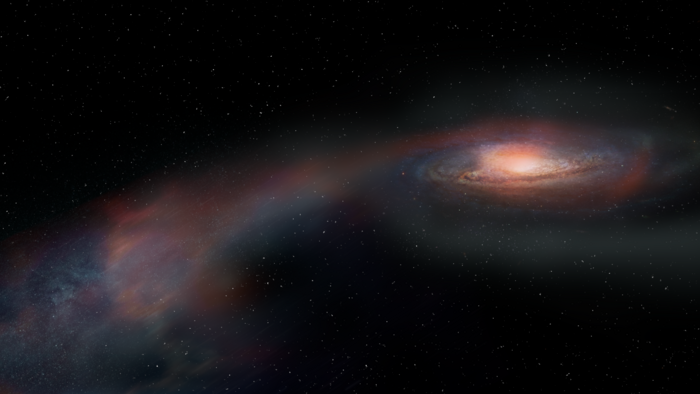

The gravitational tug-of-war between two merging galaxies could explain why star formation was snuffed out in one of them, and offers new insights into how galaxies die.

“Dead” galaxies are those where star formation has ceased, and scientists believe this happens in very old galaxies when all of the star forming gas in the galaxy is used up, or after extremely violent events.

But in a new paper published Tuesday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, an international research team from eight universities describe a new pathway to galactic death: mergers with other galaxies that forcefully remove star forming gas from their premises.

“Astronomers used to think that the only way to make galaxies stop forming stars was through really violent, fast processes, like a bunch of supernovae exploding in the galaxy to blow most of the gas out of the galaxy and heat up the rest,” Texas A&M University Astronomer and lead author of the study Justin Spilker said in a statement.

“Our new observations show that it doesn’t take a ‘flashy’ process to cut off star formation. The much slower merging process can also put an end to star formation and galaxies.”

The subject of the new study is the galaxy SDSS J1448+1010, which interested the team because it appeared to have ceased making stars around 70 million years ago, according to Dr Spilker.

“Most galaxies are happy to just keep forming stars,” he said.

But SDSS J1448+1010 is also almost finished its merger with another galaxy, so the researchers took a closer look at the galaxy using the Hubble Space Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or Alma, a radio telescope array in Chile.

What they detected were streams of material from SDSS J1448+1010 they believe were pulled out of the galaxy during the collision between the two galaxies. Such streams, known as tidal tails, have been observed around other galaxies approaching each other before merging, and are a result of the gravitational tug-of-war between the two massive collections of stars and gas.

But in the case of SDSS J1448+1010, it appears the tug-of-war was so violent, that virtually all of the galaxy’s fuel for future star growth was forced out of the galaxy, and the amount of gas being equal to greater than the mass of 10 billion Suns.

“Our observations with ALMA and Hubble proved that the real reason the galaxy stopped forming stars is that the merger process ejected about half the gas fuel for star formation into intergalactic space,” Dr Spiker said. “With no fuel, the galaxy couldn’t keep forming stars.”

While the finding hints at the possibility of a new pathway to galactic death, it’s only one observation, and it’s not yet clear if the extinction of star formation due to galactic mergers is common in the universe, or a one-off event limited to SDSS J1448+1010.

“While it’s pretty clear from this system that cold gas really can end up way outside of a merger system that shuts off a galaxy,” University of Pittsburgh graduate student in astronomy and study co-author David Setton said in a statement. “The ejection of cold gas is an exciting new piece of the quiescence puzzle, and we’re excited to try to find more examples of this.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments